Liebenberg's ME270 Students Repurpose Products for Final Design Project

December 17, 2020

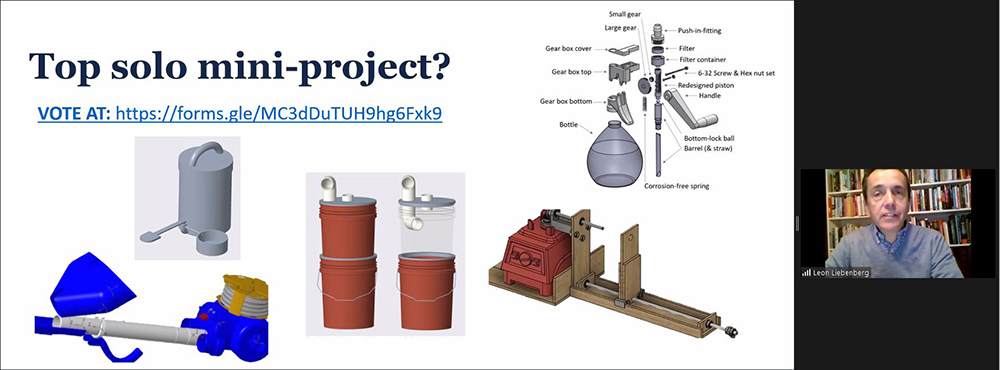

Professor Leon Liebenberg MCs the ME270 final project competition via Zoom.

Professor Leon Liebenberg MCs the ME270 final project competition via Zoom.

For students in Leon Liebenberg’s ME 270 (Design for Manufacturability) course, nothing could be more apropos than the old saying, “One man's trash is another man's treasure." For the final mini-project of the semester, the mostly Mechanical Science and Engineering (MechSE) students were to repurpose trash (a discarded product or products) into a product with a non-medical application. So, in an online competition held via Zoom during the final class period on December 8th, the top five projects were presented, after which classmates, the professor and his TAs, and special visitors invited to the session voted for their favorite. The treasure? The top three winners not only received accolades, but students with stellar final projects could contribute significantly to their final grade...and possibly come up with a repurposing design that could somehow make a difference in the world down the road.

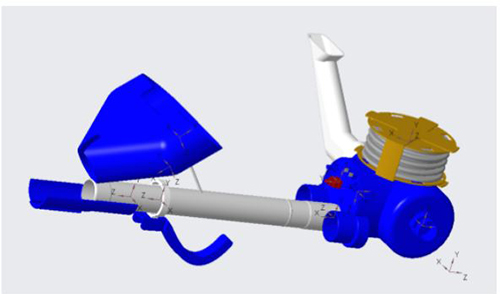

Kirsten Polen's table tennis robot made from an old vacuum cleaner.

Why do mini projects? In his course syllabus, MechSE Teaching Associate Professor Liebenberg claims they are essential exercises that will help students better understand the subject material. “Theoretical concepts and calculations have their place,” he explains, “but manufacturing and design is a hands-on experience that cannot be captured in theory and equations alone—practicalities matter deeply.”

ME270 is a practical course that demands hands-on lab exercises and project work, thus this semester’s COVID-19-mandated, online-only format proved challenging. Liebenberg recorded lab work and provided students fake lab data to manipulate and analyze. This “removed the important hands-on component of the course,” he admits. So, to compensate, he assigned low-cost prototypes students could build at home using cardboard or tape. “Such a ‘low-fidelity’ approach retains some realistic aspects of a ‘real’ product design and fabrication,” he acknowledges. Students enjoyed these exercises, reporting that “The low-fidelity approach taught them the valuable lesson of testing ideas early-on in the design process, without necessarily requiring expensive or accurate prototypes,” says Liebenberg.

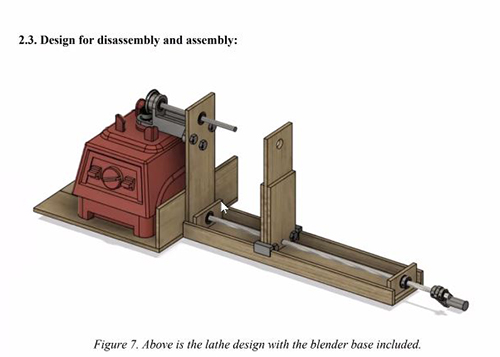

John-Luc Pec's final project: a wood-turning lathe powered by a blender.

During ME270, students were required to do six mini projects. The final project involved students finding a discarded product they could repurpose (reuse but with a different application than initially intended) with the caveat that it could not be used in medical applications. As mentioned above, their project could impact their final grade. It was to be worth 30% of their project grade (based on the six projects), which was to contribute to 65% of their final course grade.

According to Liebenberg, “One of the course outcomes is for students to redesign an existing product to meet target price, reliability and functionality goals.” He made this outcome “more contemporary” by also asking students to consider the environment when redesigning products. Then, to test their mastery of the engineering design process, students were further tasked with redesigning a product so it takes on a new purpose compared to its original purpose.

“This is not an artificial goal meant to only get the students’ ‘creative juices’ flowing,” he explains. “Rather, designing for repurposing is an important strategy for incorporating the concept of repurposing in product design, which aims to extend the longevity of products by intentionally designing features or details that facilitate repurposing.”

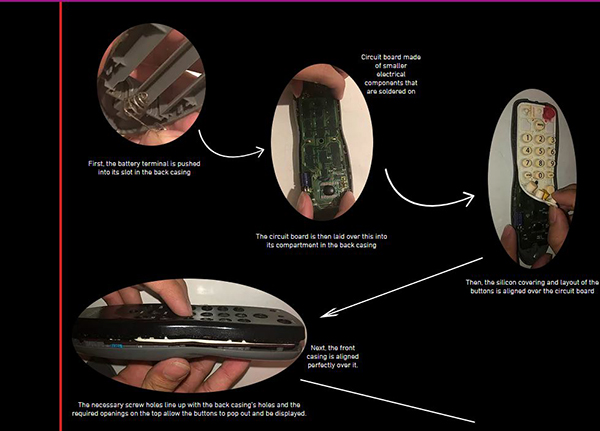

A slide from Team AB8_4's Mini-Project 1: Reverse Engineering of a Comcast Remote.

This is where Liebenberg’s dedication to the environment comes into play: the product, rather than being discarded and ending up in a landfill, is re-used “albeit in a repurposed format,” he continues. “This project therefore subjected students to real-world design challenges, contextualized by the need to produce products that have smaller ‘carbon footprints’ over the product’s lifecycle.”

December 8th, the final day of class for the semester, was set aside to celebrate students' accomplishments. For example, receiving an award for the Overall Best Performance on Mini-Projects 1–5 were members of Team AB8_4, who each received a certificate. Team AB84 was comprised of Frank Baez, Matthew Lotarski, Adithya Ramakrishnan, and Dean Wiersum.

Next, students with the top five final projects, as determined by the instructors, presented their projects. These ranged from a pet water dispenser made from a toilet; a wood-turning lathe created from repurposed shipping pallet wood and part of a blender; a mini water purifier repurposed from a plastic hand-soap pump; a sawdust separator made from plastic, 5-gallon buckets, an old Ikea shelf, and PVC pipe; and a table tennis robot made from an old vacuum cleaner. After the five presentations were made, participants were asked to vote for their favorite, based on its “Wow!” factor, as well as its technical excellence.

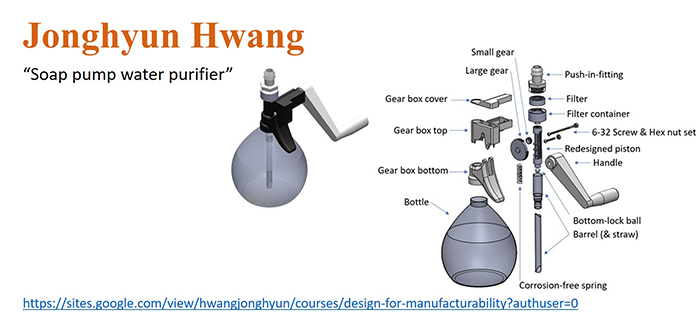

MechSE junior Jong Hwang, winner of the competition. (Image courtesy of Jong Hwang.)

MechSE junior Jong Hwang, winner of the competition. (Image courtesy of Jong Hwang.)

The winner of the competition was Jong Hwang, a MechSE junior. His portable, mini-size water purifier designed out of a discarded plastic hand soap pump was meant to be used by children who live near a contaminated water source. Liebenberg calls Hwang’s project “the most mechanically intricate design,” indicating that it was “brilliantly conceptualized, analyzed, and synthesized,” and adding that it has a “huge potential for repurposing in the ‘real world.’”

(Pleased with Liebenberg's assessment, Hwang is willing to further develop this prototype if funding, resources, or other participants are available. He invites others interested in supporting or participating to contact him: "I still see many problems with the design that can be improved," he says.)

Regarding how he came up with his product, Hwang claims, "I have always wanted to tackle major issues in the world with engineering solutions." However, instead of finding a product first and then thinking up another use for it, he chose the topic first (repurposed product for environmental & human well-being issue) and then actively sought candidate products. When looking for a discarded product, he had to look no further than the increase in plastic waste since COVID. Claiming his redesigned product may not be the most optimal solution to the problem, he says getting possible solutions out there to be seen might "trigger others to think about their solutions to the same problem and build their own. I hope my solution to the problem can initiate that process."

According to Hwang, the most challenging thing about his project was that he intended it for children: “My design focus was to reduce the force required to use this product as the target users are children,” he explains. “However, without having access to fast-prototyping tools (due to the pandemic), it was hard to approximate if the gear system I designed would effectively transfer the force and stay fit together.”

Jong Hwang's design: a mini water purifier repurposed from a plastic hand-soap pump.

He adds that, should he get an opportunity to improve his product, he “would go a few more design iterations to optimize the power transmission system."

Calling Liebenberg “the most supportive and encouraging professor I have ever met,” Hwang hopes to follow in his footsteps.

“As I also wish to be a professor and professional researcher in the future, I will try to approach my future students in a warm and supportive manner as he did to us this semester.”

John-Luc Pec, a 3rd year MechSE major. (Image courtesy of John-Luc Pec.)

Another of the five finalists was John-Luc Pec, a 3rd year MechSE major. His final project was a hobbyist-oriented, wood-turning lathe, intended to be assembled by an individual with power tools.

Pec claims that the most challenging aspect of the project was “dedicating enough time towards completing it to the standard I felt was appropriate; even when I submitted the project, I didn’t feel like it was done,” he admits.

Pec shares how he has grown through the course. “The project-oriented aspect of the class was a great way to directly apply what was learned,” he reports. “I feel as if I have a more intimate understanding of the material taught, and the design considerations brought up throughout the semester have stuck with me; I have even used some in my own personal projects.”

MechSE sophomore Mary Pelzer. (Image courtesy of Mary Pelzer.)

MechSE sophomore Mary Pelzer. (Image courtesy of Mary Pelzer.)MechSE sophomore Mary Pelzer’s project repurposes part of a toilet into a pet water dispenser, where the pet steps on a pedal and water is released into its bowl. She admits, “The hardest part of this challenge was coming up with a viable idea—the requirements were so open-ended, it was difficult to find a single good design! After I had the main idea, the rest of the work was time-consuming but not difficult.”

Pelzer believes what she learned during the course will be useful down the road. “ME270 required a great deal of independent research and creative thought,” she explains. “Through completing several team-based and independent design projects, I learned a lot about design and manufacturing that I hope to apply later on in my career.”

For MechSE sophomore Ryan Yan, who’s majoring in Engineering Mechanics, his final project was a sawdust separator repurposed from two 5-gallon buckets, parts from a bookshelf, and some PVC pipes and fittings. It’s used in conjunction with a vacuum cleaner or shop vac to remove a large majority of the dust collected before the particles reach and clog the vacuum filter.

MechSE sophomore Ryan Yan. (Image courtesy of Ryan Yan.)

Yan says the most challenging aspect of the project was coming up with and designing something useful from readily available products originally intended for a completely different purpose. “I spent hours examining various used and discarded products in my house before a light bulb finally went off in my head,” he recalls.

Yan says he “gained a vast amount of real-world knowledge” from ME270, including DFM methodologies, material selection, designing for manufacturing processes (e.g. casting, forming, and machining), design for assembly (DFA), and statistical design of experiments (DOE). “All of what I learned from the class will definitely be useful in my future mechanical engineering career,” he reports. “Therefore, I would like to thank Prof. Liebenberg for a great semester of ME 270!”

So, what kind of impact did Liebenberg believe the course had on the students? He echoes many manufacturing principles his students said they learned. For instance, for the final project, students did independent research and ideation; detailed design work and analyses, including costing analysis; and portfolios to reflect on their learning. In doing so, they learned to “recognize the fundamental relationships that operate to make products viable, feasible, and desirable,” says Liebenberg, who believes his students will be “armed with the capability to question the affordances and limitations of professional tools and practices, including the disciplinary frameworks that underpin them. I demanded a lot from the students, and they delivered!”

Mary Pelzer's Pet Water Fountain.

Plus, students gained the ability to work in a self-regulated manner—crucial with online learning as students must initiate many learning activities themselves, including those traditionally in classrooms (e.g., lecture videos, group discussions). To succeed in online learning, “It is crucial they take more responsibility for their learning,” Liebenberg insists. “This requires self-regulation skills that enable students to motivate themselves, stay on schedule, and ensure assignments are completed on time…practices like goal setting, self-evaluation, reviewing answers to previous work, and other related learning strategies that require students to act of their own volition during the learning process.” Calling self-regulation a critical lifelong learning skill, he adds that the mini-projects were hopefully successful in “attuning students to the importance of self-regulation!”

Ryan Yan's Sawdust Separator.

Story by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photographs by Elizabeth Innes unless otherwise noted.

Other I-STEM articles about Liebenberg, his pedagogy, and his MechSE courses:

- MechSE Seniors Seek to Make Congenital Amputee’s Dream of Operating Cat Heavy Equipment a Reality

- From Trash to Treasure: Liebenberg Uses Design for Repurposing to Spark Student Interest in Online Classes, Possibly Making a Difference in the COVID-19 Pandemic

- Via ENGINE, a Group of Illinois Educators Promote Using Playful Pedagogies to Engage Students

- Liebenberg’s ME 270 End-of-Semester Main Project Presentations Showcase Students’ Manufacturability Redesigns

- ME370’s Final Competition—March of the Automata—Fosters MechSE Students’ Creativity, Perseverance, and Teamwork

More: Faculty Feature, Liebenberg, MechSE, 2020

During the December 8th final class Zoom session, Professor Liebenberg asks students, instructors, and visitors to vote on their favorite mini project from among the top five.

.jpg)