At Cena y Ciencias, Illinois Scientists Shine a (UV) Light on Fluorescence

Elani Cabrera Vega and Gonzalo Campillo Alvarado interact with the young participants during the May 3rd CyC.

What is fluorescence? What causes it? On May 3rd, during the final Cena y Ciencias (CyC) outreach of the semester, students from Dual Language programs in several local schools got a chance to explore the unique property. Shedding light on the subject during the virtual (Zoom) outreach, and demonstrating the hands-on activities, were several native-Spanish-speaking scientists from Illinois. In addition to teaching kids some science and leading some fun hands-on activities—all taught completely in Spanish—the scientists also served as role models, demonstrating for the youngsters that if people who come from similar backgrounds and speak in their language can be scientists, they can too.

Lessons were led by I-MRSEC postdoc, Gonzalo Campillo Alvarado, and Elani Cabrera Vega, a chemist and new community member in Urbana, who’s applying for a PhD program at Illinois. Also sharing was Ivan Sosa Marquez, a Microbiology PhD student studying genetics and evolution of certain species’ partner quality. In addition to I-MRSEC (the Illinois Materials Research Science and Engineering Center), the home of a number of scientists who support CyC, other partners include Urbana Unit 116 and Champaign Unit 4 School Districts and parents from these districts, the state 4-H program; SACNAS (the Illinois chapter of Society of the Advancement of Chicanos/Hispanics and Native American Scientists); CPLC (the Center for the Physics of Living Cells); and Grainger College of Engineering. Also, planners wish to acknowledge funding provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF), as I-MRSEC and CPLC are both funded by NSF.

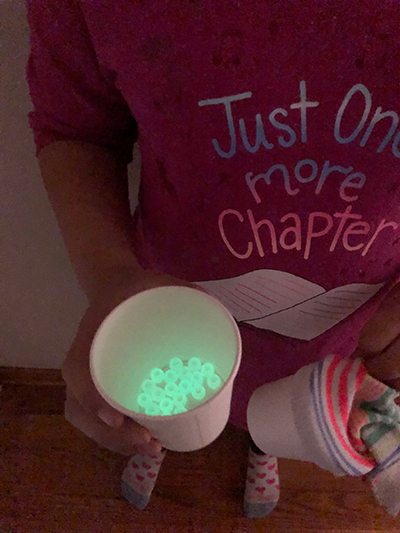

A young participant shows the special beads reacting to the UV light. (Image courtesy of Pamela Pena Martin.)

A young participant shows the special beads reacting to the UV light. (Image courtesy of Pamela Pena Martin.)

Participating children and families were from Urbana’s Dual Language programs at Dr. Preston Williams Elementary and Leal Elementary schools, plus Champaign’s International Prep Academy. Along with exposing younger students to science, another goal of the CyC planning committee was to involve middle schoolers who have been through the program or have younger siblings currently attending; thus, science students from Urbana Middle School were also involved in the event.

May’s lesson was called “Ciencia que Brilla: ¿Cómo Podemos Hacer Visible lo Invisible?” (“Science that Shines: How Can We Make the Invisible Visible?”). According to Gonzalo Campillo Alvarado, the goal of the lesson was for students to learn that our eyes can only detect a small range of light (called visible light), which allows us to see color and size of objects in our daily lives. However, some objects and animals have substances that are invisible to us until they are exposed to “invisible light,” like ultraviolet (UV), which makes them glow and reveals them! Lesson activities demonstrated that some objects respond to invisible, or UV light, by becoming fluorescent and glowing brightly.

Gonzalo and Elani used several activities to illustrate fluorescence. For example, in the first activity, they had the students use UV-beads made of a special type of colorless materials responsive to UV light. Using these beads, students explored how sunlight, a natural source of both visible and invisible (LED and UV) light changes the way we see them. In some cases, the beads glowed through fluorescence; in other cases, they changed colors due to chemical reactivity.

A secret message written in invisible ink, which a student revealed using UV light. (Image courtesy of Pamela Pena Martin.)

A secret message written in invisible ink, which a student revealed using UV light. (Image courtesy of Pamela Pena Martin.)

In another activity, students used a low-intensity UV lamp to read hidden messages CyC staff had written using invisible ink. Students discovered that, when exposed to UV light, it glowed fluorescent to reveal the message. The two also showed the students everyday objects—dollar bills, spices, even fruits stamped with invisible substances only made visible for the human eye when UV light is used. In a final activity, a white rose that was immersed in water with fluorescent ink (which was absorbed by capillarity) glowed when exposed to UV light.

According to Gonzalo, “The end goal for our lesson is to spark curiosity in the minds of the students and show them that science and nature have more to offer than what our eyes can see.” He adds that they also “would like the students to know that fluorescence and other concepts in the lesson are currently being applied for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 in clinical samples, which has accelerated COVID-19 testing in some communities.”

Gonzalo’s research, which focuses on the design and development of crystals with electronic and optical applications, is somewhat related to the lesson, in that some of the crystals he designs have the ability to glow or switch colors with light. Other materials he studies are flexible like rubber, which makes them useful components for everyday electronics like smartphones or TVs.

Gonzalo got involved with CyC because it gives him “a unique understanding of the needs of bilingual/Latino families and kids” and says it will help him “grow as an academic to better serve the community.” He first heard of CyC from the outreach office of I-MRSEC, where he does part of his research. The program immediately sparked his interest because it felt like the perfect opportunity for him to give back to the bilingual/Latino community in Urbana-Champaign, which he says has helped him and his spouse from day one.

In one demo, Elani and Gonzalo shine a UV light on a rose that has absorbed a solution that has made it fluorescent.

“During my research and teaching career,” he shares, “I have experienced the importance of having positive role models who have shared with me their enthusiasm and passion for science. In Cena y Ciencias, I would like to spark interest for science in young children who, maybe someday, can become scientists themselves.”

Regarding the positive impacts CyC has on kids and families who participate, Gonzalo claims they experience quality time together while learning fun and practical scientific concepts. Plus, the fact that it’s done in Spanish is key.

“An important component of Cena y Ciencias is that lessons are taught in Spanish,” he explains, “which is often the language spoken at home from our bilingual community in Urbana-Champaign. I believe that the presence of scientists, who are sometimes experts in their fields, with similar backgrounds to those of kids/families, can send a strong message of inclusion that shows that we all can learn and do science.”

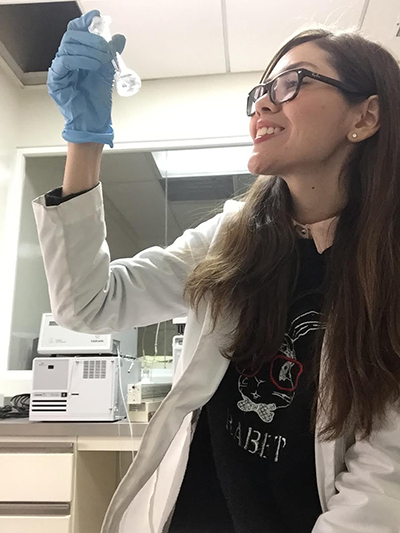

Elani Cabrera Vega at work in her lab. (Image courtesy of Elani Cabrera Vega.)

Elani Cabrera Vega at work in her lab. (Image courtesy of Elani Cabrera Vega.)

A recent graduate from a pharmaceutical sciences Master’s degree program in Mexico, Elani Cabrera Vega recently arrived to the Urbana community, where she’s applying to Illinois to study for a Materials-Science-focused PhD. During her Master’s program, she designed biomaterials based on DNA that are able to detect antiparasitic drugs.

Elani felt right at home teaching the CyC youngsters about fluorescence. Before arriving to Urbana, she had taught biology and chemistry labs for middle and high school students in Mexico, and as part of that, taught fluorescence and phosphorescence, also showing students different experiments about these two types of luminescence. She reports that studens said it was one of their favorite lessons!

So, how’d she get involved with CyC? Elani shares that when she first arrived at Urbana, Gonzalo told her about it and invited her to participate. Her first experience was with the December 2020 lesson: “Cristales escondidos en tu cocina,” where she helped him with the experiments. “I really enjoyed how kids were involved and had interesting questions about science,” she says. “This made me remember how much I enjoyed teaching and sharing science with my students in Mexico.”

In addition, like Gonzalo, she too hopes to convince Hispanic young people to consider becoming scientists by serving as a role model. “I think that science should be for everyone, not just for who society considers ‘smart’ or a few, and we must remove stereotypes about it because everyone can learn and understand sciences, no matter the age or background.”

In terms of the positive impact she hopes CyC is having on kids who participate, she wants to help them “feel that they are capable of learning scientific knowledge, no matter their age or cultural background.”

Elani is also excited about the family component of CyC. She believes it’s important that families “learn along with their children and see their children’s abilities, interests, and curiosity to understand the world and their environment. This is very important because the parents will believe more in the potential of their children and know how to help them in their education.”

Concerning CyC’s mission to increase the number of underrepresented minorities in science, Elani says: “We are living in a society who still believes that science is only for ‘smart people’ or for kids who have the opportunity to get ‘good’ or privileged education, and that is not true. Science must be more inclusive with different cultural backgrounds and ages. There are many inspiring Latino scientists and from other underrepresented minorities who have contributed to scientific advancement, and we need more! That is why I wish that the Latino community of children in Urbana-Champaign can experience science without stereotypes and barriers of language, culture, or age.”

Finally, Elani is grateful to be able to pass it forward by being a part of CyC because as a child, she “would have liked to receive this support, encouragement, and education,” she admits. “It would have helped me to trust more in myself about my dream of being a Mexican woman in science.”

Ivan Sosa Marquez interacts with the young CyC participants.

One of Ivan's slides about animals that shine. (Images courtesy of Ivan Sosa Marquez.)

Also sharing near the end of the lesson was Ivan Sosa Marquez, a Microbiology PhD student researching symbiotic processes like the Legume-Rhizobia symbiosis and functional genetics. (For instance, legumes, such as soybeans, are able to form a symbiotic relationship with nitrogen-fixing soil bacteria called rhizobia. As a result of this symbiosis, nodules form on the plant’s roots, which allow bacteria to convert nitrogen in the atmosphere into ammonia that the plant can use.) Ivan shared with young participants that an angler fish has a similar symbiotic process with bacteria that allows it to hunt with a specialized organ.

Ivan got involved with CyC because he wants “to extend scientific knowledge to society, especially Latinos.” Regarding the impact of the May 3rd CyC, he says, “I thought the conversation was exciting and interesting, and they learned or developed curiosity for something new to explore.” Ivan agrees with Gonzalo and Elani that presenting science in a student’s native language is important: “Science is complicated by itself,” he claims. “Imagine translating it!”

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: Cena y Ciencias, I-MRSEC, K-6 Outreach, SACNAS, Underserved Minorities, 2021

For other I-STEM articles about Cena y Ciencias, see:

- Virtual Cena y Ciencias Provides Hispanic/Latinx Role Models, Encourages Hands-on “Kitchen Science”—All Done in Spanish

- Cena y Ciencias—Science Demonstrated in Spanish by Hispanic Role Models

- Cena Y Ciencias Exposes Hispanic Elementary School Students to Materials Science at MRL

- Polímeros! Cena y Ciencias Program Teaches About Materials Through a Supper & Science Night

- Leal Science Night Exposes Local Youngsters to STEM, Role Models

- Cena Y Ciencias: Supper and Science…and Role Models, Courtesy of SACNAS

During Elani Cabrera Vega and Gonzalo Campillo Alvarado's presentation at the May 3rd CyC about fluorescence, Elani shines a UV light on a secret message written in invisible ink to reveal the message.

During Elani Cabrera Vega and Gonzalo Campillo Alvarado's presentation at the May 3rd CyC about fluorescence, Elani shines a UV light on a secret message written in invisible ink to reveal the message.

.jpg)