Banerjee and Bose Empower/Recharge Educators During CISTEME365 Session About Power and Energy

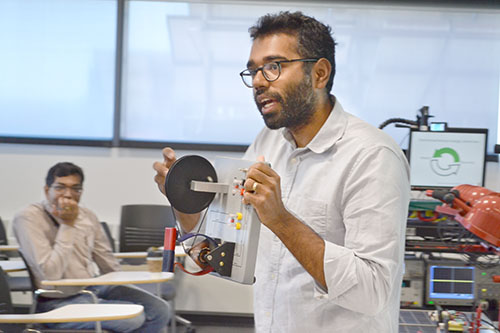

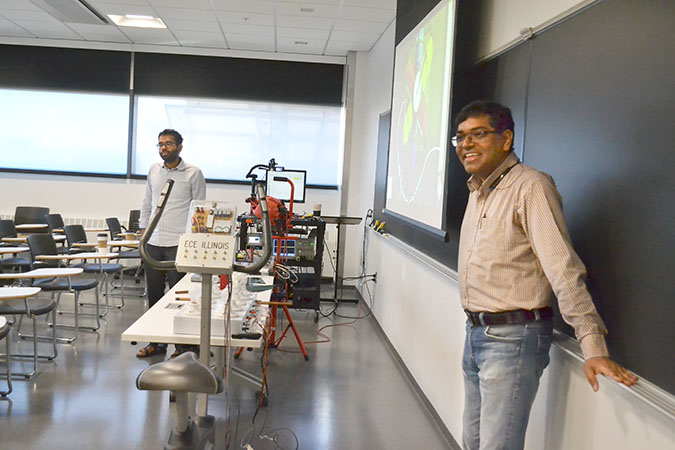

Subhonmesh Bose does a demo for the educators.

September 16, 2019

In the recent CISTEME365 Institute from July 22–August 3, 2019, two rising stars in Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE), Assistant Professors Subhonmesh Bose and Arijit Banerjee, presented a session on their areas of research—power and energy— to 13 educators participating in the institute. Part of the 3-year NSF grant, Catalyzing Inclusive STEM Experiences All Year Round CISTEME365, their integrated presentation walked through a history of power systems, the physics behind electromechanical energy conversion, and shared research frontiers in power and energy. Plus, a dialogue ensued where both the K–12 and higher education teachers discussed STEM pedagogy beneficial for all ages.

Bose and Banerjee’s session was replete with fun and exciting demos. But first, they taught baseline principles about their areas of expertise, then used fun demonstrations to underscore the principles taught.

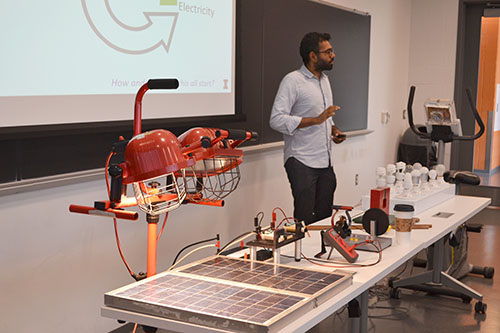

Subhonmesh Bose discusses how solar energy can be used to impact the power grid.

Subhonmesh Bose discusses how solar energy can be used to impact the power grid.For example, Bose discussed principles related to his research on the electric power grid, which addresses algorithm and market design questions that arise in integration of variable renewable and distributed energy resources in the grid. To achieve his goals, Bose says he utilizes optimization, control theory, microeconomics, and game theory tools. His current projects include optimization of dispatch with variable wind, designing meaningful prices for wholesale electricity markets under uncertainty, market design for multi-area power systems, and electrification of transportation.

One principle Bose sought to convey to the Institute educators was this: “Electricity generation largely relies on conversion of mechanical motion to electricity,” So, to illustrate this principle, he solicited the help of various educators in a demo where participants used a stationary bike to drive electrical current through a series of light bulbs.

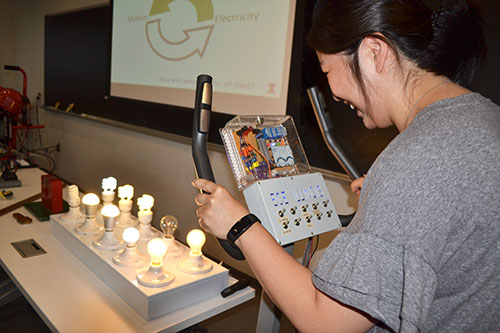

Pedaling a stationary bike, Elizabeth Ohr, Urbana High School Science teacher, produces enough current to light up all the bulbs but one.

Pedaling a stationary bike, Elizabeth Ohr, Urbana High School Science teacher, produces enough current to light up all the bulbs but one.“The harder you push, the more bulbs turn on,” he explains, adding that “The same principle underlies electricity generation from power plants that use fossil fuels such as coal or natural gas, nuclear technology, or the force of flowing water (hydroelectricity).” The educators also got a sense of the degree of mechanical energy required to make the bulbs light up—no matter how long or how hard they tried, none were able to make the final light bulb turn on!

Also related to energy, Banerjee’s research involves advancing energy conversion by functionally integrating power electronics, electromechanics, and control, especially via creating new energy conversion architectures. Some real-world applications of his research include: renewable energy systems, robotics, system-level monitoring and diagnostics, and, like Bose, electric transportation systems.

Banerjee also treated the teachers to several fun demos. In fact, he says these are the kinds of things he does in his classroom to engage his students. Not only that, he admits, “I myself get bored in my classroom if I don’t bring demos!”

Arijit Banerjee does a power demo for the educators.

Arijit Banerjee does a power demo for the educators.Regarding his use of demonstrations as part of his pedagogy, he admits, “A major challenge that students face in the classroom is connecting math and theory with the craft of real-world systems. I love to conceptualize and create interactive demos that can provide a context-based learning framework.” According to Banerjee, these demos enable an engaging environment in his classrooms that bring students to the center stage “rather than me blabbering for hours,” he admits. “The classroom becomes more of a discussion forum.”

Plus, while learning from a textbook is important, it’s not the end-all in terms of instruction and learning. “Many times these demos help me show students the boundary of textbook knowledge,” he says.

Plus, the demos aren’t just to keep the students engaged; according to Banerjee: “It keeps me excited about teaching,” he confesses.

Elizabeth Ohr, Urbana High School Science teacher, helps out with a demonstration by pedaling a stationary bike in order to make the light bulbs glow.

Elizabeth Ohr, Urbana High School Science teacher, helps out with a demonstration by pedaling a stationary bike in order to make the light bulbs glow.While Bose used the stationery bike/light bulb demo, he acknowledges that he himself is a theorist, so his demonstrations are often computer simulations. However, because his colleague, Banerjee, is excellent at designing hardware-based demonstrations to use in his classes to explain concepts, Bose has invited him to show some of these demos in his own classes, “to make the subject come to life.”

“Students enjoy a lot when concepts are linked to tangible outcomes,” he continues, “whether in simulations or in hardware implementations. It motivates them to learn the abstract concepts. Theory taught in isolation requires an effort on the student’s part to extrapolate and see the application. Showing that ‘It works!’ is typically better than saying ‘It can be applied.’”

Bose and Banerjee say they taught a session in the CISTEME365 Institute partly to help out a colleague, Lynford Goddard, PI of the grant, and also to vicariously impact younger students.

For Bose, it’s especially the latter. He says he’s presented at a couple of summer camps over the last several years, including Goddard’s GLEE camp. He says these presentations allow him to reach an audience he seldom gets to interact with: K–12 students. “I am motivated to inspire K–12 students to pursue STEM fields. I personally find my field of study exciting and rewarding; I hope to convey that excitement to students.”

Arijit Banerjee (left) listens while Subhonmesh Bose teaches the educators about his research about power.

Arijit Banerjee (left) listens while Subhonmesh Bose teaches the educators about his research about power.Bose adds that he was happy to contribute to Goddard’s effort in the program, reporting that: “CISTEME provides the rare opportunity to talk to the educators who work with these students on a daily basis.”

Arijit Banerjee indicates that he got involved with the CISTEME365 Institute because of his relationship with Lynford Goddard. “To be honest, it is because of Lynford,” he admits. “He has been one of my amazing mentors in the department. At the end of the day, I feel happy being a part of the ECE/U of I family and helping one another drive impact.”

Anita Alicea, a STEM integration specialist at Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy in Chicago participates in a demo during Bose and Banerjee’s power and energy session.

Anita Alicea, a STEM integration specialist at Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy in Chicago participates in a demo during Bose and Banerjee’s power and energy session.Regarding the benefit of bringing K–12 educators to campus and interacting with them, Banerjee shares what impact he feels the program had on the teachers. “CISTEME365 is a tremendous program, not only for the teachers who are coming to the campus, but also for us,” he admits. “We share each other's strengths and challenges and learn from each other.”

Banerjee claims that he and Bose often discuss pedagogical philosophies at length, even more than about content, discussing more thought-provoking questions, such as “How do we engage students?” and “What is the role of teachers in the present education scenario?” He says the two hoped the same would be true when teachers come to these sessions.

“We do not know everything—the more we share, the more we learn,” claims Banerjee. “I hope the teachers who came this time will go back to their respective institutions recharged and rejuvenated, expanding their knowledge horizons, and more importantly feeling appreciated for all the hard work they put in to create better human beings.”

Similarly, Bose also agreed that the interaction with the K–12 educators and the discussion regarding pedagogy was beneficial for all involved.

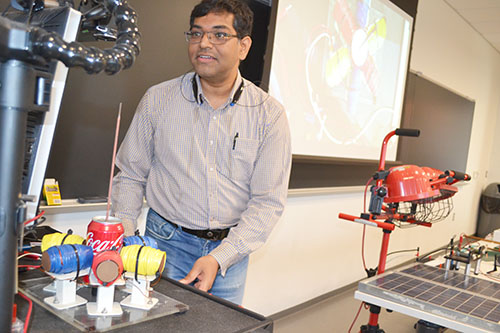

Arijit Banerjee discusses electromechanical energy conversion with the educators.

Arijit Banerjee discusses electromechanical energy conversion with the educators.According to Bose, “We, the professors, are educators ourselves. We face challenges in classrooms that are similar to those faced by teachers in middle and high schools. The CISTEME program is a great opportunity to cross-pollinate ideas and learn from each other. Through this interaction, I learned more about the classrooms of the students before they join the university. The better I understand the background of the students, the better position I am in to give them a good learning experience.”

Bose adds that in addition to Institute participants being exposed to the professors’ views and styles of teaching, the K–12 teachers got to see the frontier of research in various fields. “Linking modern innovation and research directions to class material will hopefully make the class material more exciting to students,” he claims.

However, while the educators loved the demos, the idea is for them to take what they’re learning and try to implement it in their classrooms and after-school clubs. One challenge might be the lack of similar high-tech equipment.

Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy’s arts instructor, Irica Baurer, gets all but the final bulb to light up when doing the stationary bike demo.

Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy’s arts instructor, Irica Baurer, gets all but the final bulb to light up when doing the stationary bike demo.However, Bose claims some demonstrations don’t require high-tech equipment. For example, he cites Banerjee’s explanation of Lenz’ law, using a magnet and a chalk passing through a copper tube. “Albeit simple,” Bose states, “the demonstration is quite powerful to explain concepts in electromagnetism. Such demonstrations, I would imagine, are easy to implement.” While he says some of the other demos that Banerjee designed require skills that may be challenging to replicate, he suggests that if such tools were standardized and produced in bulk, these types of demonstrations could reach a wider audience.

Regarding the equipment for his demos, Banerjee reveals that he’s been very fortunate to obtain support from ECE and its Grainger Center for Electric Machinery and Electromechanics in order to create the demos and the overall demonstration framework he uses. “It is a lot of investment of resources and time and not easy to replicate at scale,” he admits.

However, one of Banerjee’s outreach objectives is to help teachers develop low-cost alternatives in order to implement his demos in their classrooms. Over the next few years, he plans to share the blueprints and work with the teachers to find low-cost alternatives to create these demos at scale in order to demonstrate the same physical principles.

Author/Photographer: Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: CISTEME365, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Teacher Professional Development, 2019

For additional istem articles on CISTEME365, please see:

Subhonmesh Bose and Arijit Bannerjee discuss STEM pedagogy with the educators.

.jpg)