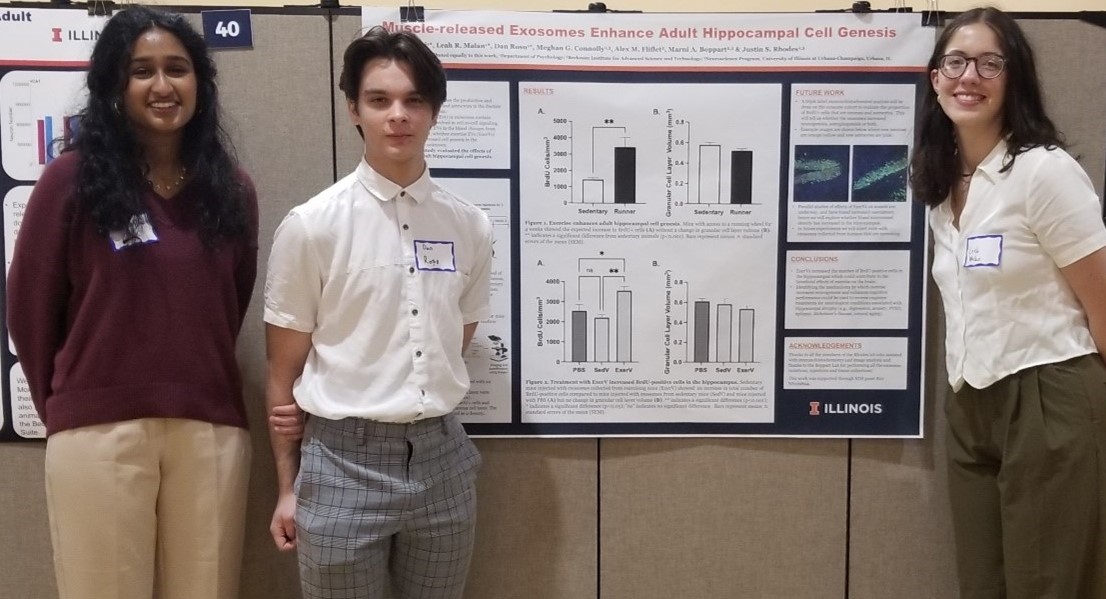

Five Schools Tap into CISTEME365 Resources to Begin STEM Clubs, Pique Student Interest in STEM

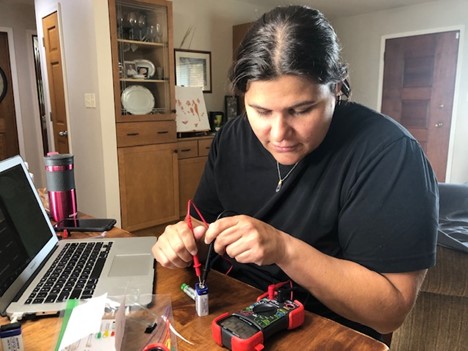

Chicago Vocational Career Academy’s instructional technology teacher, Lillian Perteete, solders the circuit she’s making.

September 12, 2019

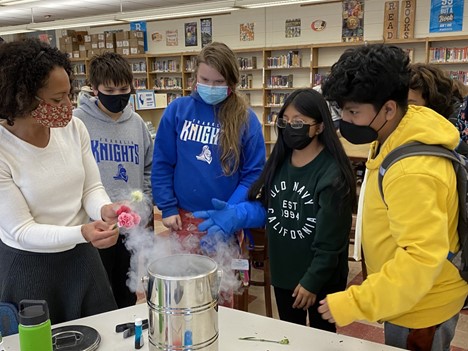

With the goal of increasing the number of their students, especially girls and minorities, who become interested in, and possibly choose careers in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics), 13 teachers from five schools are participating in Electrical and Computer Engineering’s new NSF-funded grant, CISTEME365 (Catalyzing Inclusive STEM Experiences All Year Round). The main objective of the program is for the educators to begin after-school STEM clubs in their schools. As part of the program, for two weeks this past summer, from July 22–August 3, 2019, the schools sent IDEA (Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access) Teams to campus for the first CISTEME365 Institute. There, the educators learned how to foster equity and inclusion. They tried out hands-on activities CISTEME365 PI Lynford Goddard had designed for his long-standing electrical engineering summer camp, GLEE, and that would expose students in their clubs to STEM. Plus, they networked with other educators excited about STEM. According to Goddard:

“The idea is that we want to be able to interact with students from across the state,” Goddard says. “We want to be able to transition the curriculum from GLEE to students throughout the state.”

Participating in the 2019–2020 CISTEME365 cohort were educators from three Chicago Public Schools: John M. Smyth IB World School, plus two high schools: the Chicago Vocational Career Academy and the Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy. Two local schools also participated: Urbana High School and Mahomet-Seymour High School. Each school’s team was comprised of three members: a teacher, a counselor, and a third person (another teacher or counselor, STEM specialist, vice principal, or even interested parent). In actuality, team sizes ranged from 2–4.

Several teachers from the participating schools shared why they wanted to participate in CISTEME365, and how they hoped to impact the students in their schools regarding STEM.

Donnell White, a science teacher at John M. Smyth IB World School.

.jpg)

Stephanie Miller, Smyth Counselor, watches the educator across from her doing the Logarithm activity.

John M. Smyth IB World School

Donnell White, sixth grade math teacher and International Baccalaureate Coordinator for sixth through eighth grade at CPS’ Smyth School, shares why he participated in the Institute: “Because my principal mentioned a buzz word that I like—and that is STEM. I strongly believe in it.” In fact his kids studied engineering and computer science at Stanford. So when he heard the word, STEM, and when the principal gave him more details about this program and what they intended to do, he jumped at the chance. “So yeah, just excited,” he admits.

White says that at this stage, Smyth has minimal clubs, and as far as STEM clubs, they have nothing. “This will be our first chance to get going into this direction,” he says.

White explains the importance of emphasizing STEM: “I really think that's where the world is headed. There's a lot of wealth of money. There's a lot of attitudes and beliefs about where things need to go and can't go. And technology is at the very forefront, and the United States has actually been outpaced by some countries nowadays. So I love that we're starting to recognize we've got to do even much more than what we've been doing.” According to White, the STEM camp they’re going to start is a good step in that direction. “I want to see kids turned on to STEM type of, not only careers, but activities where they actually buy into it, and they love it, and enjoy it.”

While White works with sixth graders, he says kids should be exposed to STEM “in the primary grades,” he claims. “I have no doubt on that," then goes on to recall what his daughter, a civil engineer now, was like as a little girl. Even in preschool, he says, “She always had this knack for wanting to observe, start taking notes. But the point is, early on, she had a lot of science yearning inside of her. But I think kids can be brought up to recognize STEM as something they can be a part of, even in the primary grades.”

Stephanie Miller, a Smyth counselor came to this institute to “not just have a group of individuals that I could partner with, but look for some tools or resources that I will be able to share with my students in hopes that I will be able to get them more interested in taking some of the STEM pathways.”

A pre-K through eighth school, Smyth has an International Baccalaureate curriculum, which focuses on a global perspective—getting students prepared to be global thinkers and not just focused on what's going on around them locally, “which fits really well into this whole idea of trying to increase underrepresented groups in the STEM field,” she indicates.

Miller says the role of an elementary school counselor is somewhat of an administrative role—to make sure they're targeting several relevant areas for every student. “You are responsible for every student in the building, and not just the students’ social, emotional well being, but the whole student. So how that student views academic performance, how that student views their surroundings, the city that they come from—how all of those dynamics, academic, social, emotional, and college and career readiness play into the student and how they come into your school building every day.”

Chicago Vocational Career Academy English teacher Zenobia Jefferson enjoying the soldering hands-on activity.

Chicago Vocational Career Academy

Zenobia Jefferson, who teaches English as well as Exploring Computer Science at Chicago Vocational Career Academy, shares why she participated in CISTEME365: “Because I love exploring computer science,” she admits. “I love technology.” While their school has a STEM club, she doesn’t think it embraces the entire STEM concept—it mostly addresses technology.

Regarding the equity portion of the institute, her school is 99% to 100% African American, so they don’t deal with inequities when it comes to race. However, she feels encouraging girls to embrace STEM is an area they need to grow in. But she doesn’t necessarily see it as a school situation, but more of an African-American culture issue. She shares an example from when she was teaching Exploring Computer Science.

Lillian Perteete, Chicago Vocational Career Academy’s instructional technology teacher, prepares to test her circuit.

“I was trying to encourage some girls to go into it. All they want is to go into Cosmo. I'm like, ‘Do you not realize what you can do with this?’”

Jefferson believes not just the girls, but African-American students nationwide don't quite grasp the concept of what they could actually gain if they went into STEM. “I think many African-American students are geared towards sports and entertainment, and they don't see the value of going into STEM careers or even their ability to grasp these concepts.”

She adds: “They might say, ‘I like math. I like science,’ but they don't say it to the extent of ‘I can have a career in these fields.’ And I think that's where the shortcoming lies.”

While she’s not really in charge of the STEM club per se, she has big hopes for the club. “I'm praying, yes, I am praying that we can nurture a culture or reverse a culture in school so that the kids start looking at it differently.”

Jefferson goes on to admit that her students might experience a lot of successes in the area of STEM, but those successes are seen in isolation. She says that perhaps a student “went to this club, and went to that club, and they won first place. Great. But how do you transfer that skill to the other components? How do you, say, nurture that climate in a school of: ‘This is a good thing. This is something to consider!’? She insists that culturally, there needs to be a climate change in regards to African-American students.

“We have to change that climate. ‘Well, you know, the boys’ basketball team won first place!’ Good. But what about science and math? We need to nurture that more.”

Lemond Peppers, a student engagement advocate from Urbana High School, solders the circuit he’s making.

Urbana High School

Lemond Peppers is a Student Engagement Advocate for grades 9–12 at Urbana High School. He says his main purpose in participating in CISTEME365 was “to try to work at being a central bridge to get more students of color, specifically African-American males, but African-American males and females, into STEM curriculum.” Further, his goal was: “So they begin to understand that STEM curriculum has, right now, concrete, tangible careers and positions that are out there for them that are attainable.”

Regarding the breadboards with coils activity they'd completed, Peppers boasts, “And I got mine to work.” He'd done something similar back in high school, but not with breadboards. “I think we were using cardboard back in my day, but it's been since chemistry and physics classes, so they're doing these same kinds of experiments, but we're using higher technology. We're not taping on cardboard anymore, and we're not having to rely on the wind. It's eye opening.”

Peppers shares his goal when he goes back to his school: “To get in front of the administrative staff, to get in front of the teachers, and say, first, “We need this!” My district is kind of running—not behind—but there's some things we just don't have in place as far as STEM curriculum is concerned.”

In regards to the proposed STEM club, he says, “We've got to bridge this beyond the stereotypical White male and Asian students; we have to get young African Americans in this. We can't say that they're not important. We have to make them an investment.”

.jpg)

Mahomet-Seymour chemistry teacher Terry Koker enjoys doing the soldering activity.

Mahomet Seymour High School

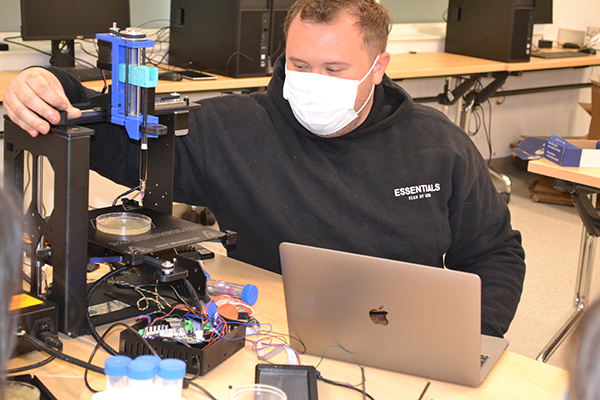

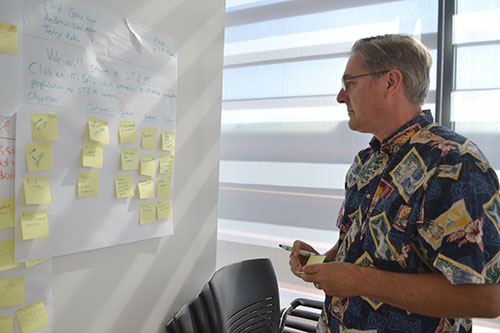

For Terry Koker, who teaches chemistry at Mahomet-Seymour High School, CISTEME365 wasn’t his first professional development opportunity at Illinois. In fact, in his whole career of 35 years, he’s probably spent 15–20 summers at Illinois, growing and learning—what he terms, “moonlighting over the summers at the university.”

While Koker participated in CISTEME365 because his teaching area is STEM, he also admits, “Dr Goddard was a big part of it.” For example, over the last several years, Koker has conducted research in Goddard’s labs as part of the recent Nano@Illinois RET program. So when Goddard started planning for this project, the local high school teacher, who is “in the trenches” so to speak—teaching STEM to high schoolers day in day out—agreed to be on the board to help plan the program and discuss some of the options for the grant. So while Koker feels “a certain loyalty to the project,” he acknowledges “but it does fit what I want to do as well.”

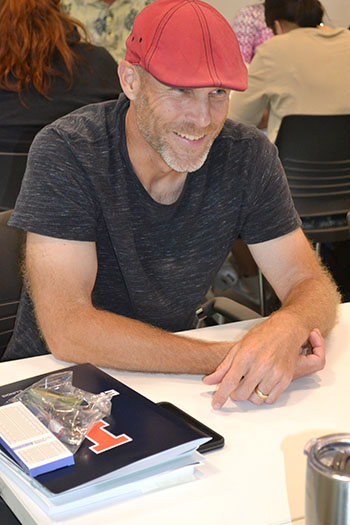

Neal Garrison, a Mahomet-Seymour High School counselor.

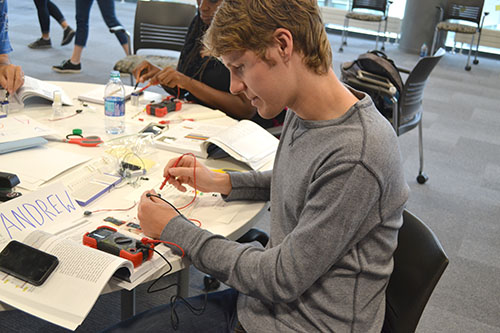

Other members of his team were school counselor Neil Garrison, along with a former student of his from Mahomet, Andrew Walmer, who appears to be following in Koker’s footsteps; hoping to be a secondary school science teacher, he’s currently studying teaching of chemistry at Illinois. Walmer was included to provide perspective of what it was like to be a student at Mahomet-Seymour. “So he has a good sense of how the school works, and he's going to help us with the club.”

While the projects are a bit out of the chemistry field and more electrical engineering, Koker knows he might not gain activities he can use in his chemistry classroom. (But he is interested in electrical engineering; he has a Master's degree in electronic materials that he got at Illinois in the mid 90’s). But Koker hopes their new STEM club will provide “just one more opportunity for me to interact with kids, and get them excited about science. I try to do that in my classroom obviously, but this is a chance to work with kids that are maybe not in my class, but are in the STEM club.”

While Mahomet-Seymour doesn't have a lot of people of ethnicity, they hope to broaden participation by women. “That's one of our major goals, a 50-50 gender representation.” He claims that many of the school’s academic teams are 50-50, “So definitely a goal that we're gonna’ try to work hard for on our STEM club…We're going to be very intentional about that, trying to make sure it is. I know that some research has shown that middle school is an age where, especially girls, turn off to science.”

Andrew Walmer, a Mahomet-Seymour alum and current Illinois secondary science teacher candidate, tests the voltage of the circuit he built.

While their students are already past that age when they walk through their doors for the first time, Koker believes many of Mahomet’s AP classes in STEM are still a 50-50 mix. “So they're not dropping out of the classes, whether they still see themselves as able to do it in college or not. Because if they could do it in an AP class, they can do it in college, because that's college-level material.” So he says they’ve got confident kids with good self-efficacy in their upper-level students. “So now, the next thing is, ‘Okay, what about the level down? What about the kid that maybe doesn't take AP chemistry? What about the one that doesn't take AP calc? How do we get them as freshmen, sophomores and open that door to them that they could do it as well and do it with not just the boys, but a mix of the two?”

As someone who helped plan the institute, how does he think it went? “It went well,” he says, adding: “I just appreciate the opportunity to do this, these two weeks, and I've had a lot of fun. It's kinda’ right down my alley!”

ECE student Maddie Wilson helps Anita Alicea, the STEM integration specialist at Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy, with her breadboard.

Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy

Another participant at the Institute was Anita Alicea, a STEM Integration Specialist at the Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy in Chicago. Begun six years ago, her school has 900+ students, grades 9–12. Alicea explains how she ended up participating in CISTEME365. When this particular professional development came across her desk, she saw it as a new opportunity to further expose their students to STEM. “As the integration specialist, I thought this was another opportunity in the engineering eyes, because we are using the engineering design process. Why not find out what engineers actually think and do?”

Alicea brought three colleagues with her: Vernon Rogers, a diverse learning teacher; Irica Baurer, a fine arts teacher, and a counselor, Nancy Rodriguez, the school’s college and career coach, who informs students about their postsecondary options once they graduate.

Alicea proudly claims that “every student at Sarah E Goode has been exposed to STEM.” In fact, as part of their CIWP (Continuous Improvement Work Plan), every teacher must have a connection in their curriculum to the school’s STEM Fest at the end of the every year, where everyone in the building can see what has been happening in every classroom. Indicating that every student is exposed to STEM in different ways.

“We're trying to make sure that when they go into a math class, or English class, or Spanish class, a PE class, that they have been exposed to STEM in some form or fashion,” she maintains.

CISTEME365 PI Lynford Goddard watches as the Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy’s Post-Secondary Coach, Nancy Rodriguez, tests the circuit she built.

To foster that STEM exposure, the school has partnered with Daley Community College and also IBM, offering two IT pathways. In fact, a Daley College representative and an IBM liaison are actually at the school several days a week to interact with students and ensure that they have the correct courses, enough credit hours, an internship, even an Associate’s degree, so that upon graduation, the might have a job lined up. For example, about two or three students have actually had been offered jobs at IBM, and two former students currently work for IBM.

Where does Goode’s partnership with CISTEME365 come in? The school just added a third pathway: engineering, and claims the STEM club they’ll be starting as a result of CISTEME will help with that. “So this is another resource, another tool for our students to see what it is that they can do with STEM and a career in STEM.”

.jpg)

Vernon Rogers, the Diverse Learner Instructor at Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy, shows off his team’s poster about students’ perceptions of STEM, an activity during the first week of the institute.

According to Alicea, STEAM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts, Mathematics) is also very big in their school. So they brought a fine arts teacher to participate in the institute, Irica Baurer, who was “Just excited to be here!” According to Baurer, the visual arts department and civics annually collaborate on a project where students do engagement work that is socially responsive. The students choose something that is meaningful to them, then integrate it with aspects of STEM, using art and technology to be able to show it. For example, last semester they created plays and stories related to social justice, and then recorded and edited them, working with a professional editor. Those were their STEM Fest projects.

Regarding the CISTEME365 breadboarding activity, Baurer says it wasn’t the first time she had used a breadboard. A lead teacher for a summer STEM camp, she had taught children how to code using a TI graphing calculator with a breadboard attached. So, when she recently had the breadboard in her car replaced,” she explains, “I knew exactly what they were speaking about.”

Sarah E. Goode STEM Academy’s arts instructor, Irica Baurer, tests her circuit.

Through the STEM club Goode will be starting, Baurer plans on “bringing awareness to myself, bringing awareness to children, because STEM is all around—everywhere we look, even in your cars because they're smart cars. Everything is smart technology, so knowing the smart technology. I felt really good that I knew exactly what they were getting ready to replace in my car,” she adds.

Author/Photographer: Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: CISTEME365, Electrical and Computer Engineering, Teacher Professional Development, 2019

For additional istem articles on CISTEME365, please see:

ECE student Wynter Chen (center) helps Urbana High School Science teacher Elizabeth Ohr and student engagement advocate Lemond Peppers with the breadboard activity.

Terry Koker works on his team’s action plan.

Lemond Peppers and Anita Alicea chat about what they believe their students think STEM is.

.jpg)