On Her First Foray into STEAM, Kathy Walsh Acquaints Franklin Students with Microscopy, Haiku

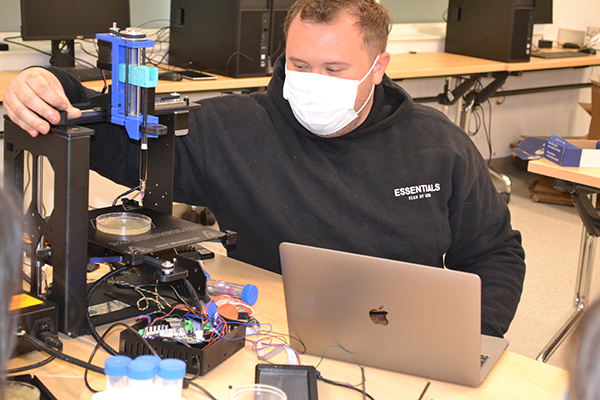

MRL scientist Kathy Walsh shows Franklin students a Hello Kitty pencil she's going to analyze under the 3D optical profiler.

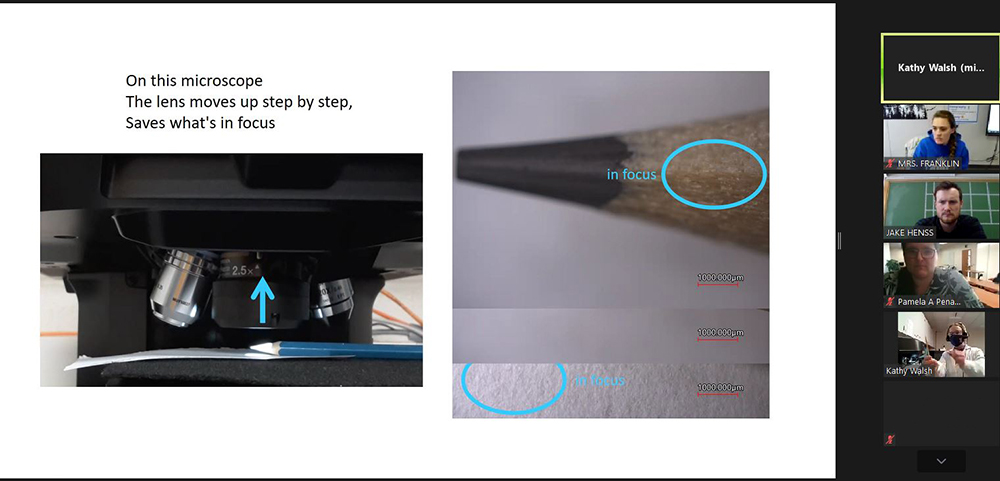

On this microscope

The lens moves up step by step,

Saves what's in focus.

February 17, 2021

The above haiku by Kathy Walsh describes one of the toys the MRL scientist gets to play with day in, day out—a 3D Optical Profiler. Specializing in nano/microscale surface topography, she uses the instrument to help researchers in their materials analysis by taking very accurate 3D measurements of the roughness or height of a material’s or specific object’s surface. So, when presented with the opportunity to participate in I-MRSEC’s Musical Magnetism curriculum and share her love of microscopy with Franklin STEAM Academy seventh and eighth graders, she jumped at the chance. Also thrilled that the program’s STEAM emphasis meant adding the Arts to STEM (Science Technology, Engineering and Mathematics), she further embraced the opportunity to expose the young people to another passion of hers—writing haiku about science.

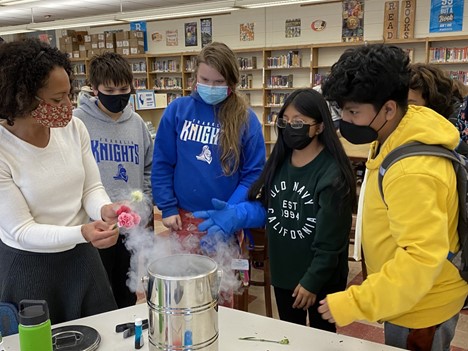

Walsh taught a couple of sessions of the six-week curriculum. On Wednesday, February 10th she taught students how scientists use light to study materials and measure things. She introduced them to LiDAR (Light Detection and Ranging), a remote sensing method that uses light in the form of a pulsed laser to measure ranges (variable distances) to the Earth, as well as the 3D optical profiler, a microscope which similarly measures the roughness of various surfaces. On Thursday, February 11th, she discussed image processing, elaborating on the photos she’d taken of various surfaces the day before, then led students on a foray into science haiku writing.

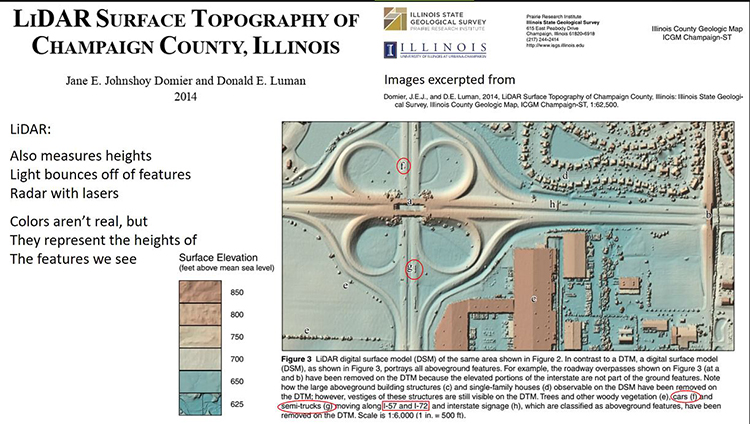

A LiDAR image taken of the interstate in Champaign County which Kathy Walsh uses to show the Franklin students how LiDAR assigns different colors to objects of various heights in the image.

For instance, one slide about LiDAR she used in her presentation contained a haiku she’d written about the imaging tool.

LIDAR

Also measures heights.

Light bounces off of features.

Radar with lasers.

Colors aren’t real, but

They represent the heights of

The features we see.

Regarding the opportunity to introduce the young people to her area of expertise, she was careful to avoid jargon as much as possible—something she’d learned about during another I-MRSEC outreach, the AAAS Science Communication Workshop in fall 2020.

“This time, I was particularly trying to keep in mind the thing that really stuck with me from the workshop—being aware of specialized terminology and not introducing more jargon than is actually necessary. For example, I tried to say ‘microscope’ instead of ‘3D optical profiler’—both are accurate, but one term is more intuitively understood, if less precise.”

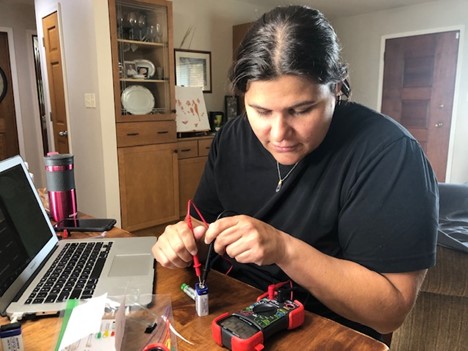

Kathy Walsh adjusts the 3D optical profiler to give Franklin students a closer look at the pencil she and the students are analyzing.

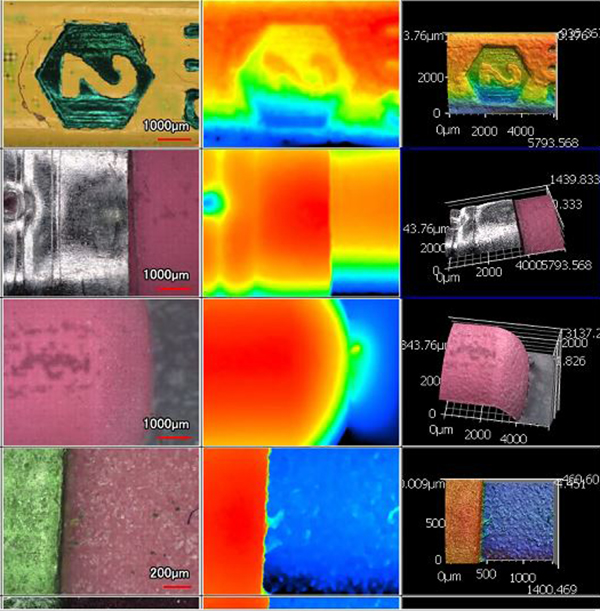

Walsh elaborates on what she was trying to communicate to the students during her two sessions. For instance, on Wednesday the 10th, after introducing students to her area of specialty, she and the students took a close-up look at pencils. “Ordinary objects look awesome in microscopes—surprisingly awesome!” she explains. “Something as simple as a pencil has a great deal of depth and detail to the features, and you don't have to study exotic things in order for microscopy to tell you a lot about the world.”

Of her activities on her second day, which dealt with image processing…and poetry, specifically haiku, she hoped to help students develop their skills in expressing themselves. “Communicating science goes better if you have a certain facility with turns of phrase and conciseness of expression. Surprisingly, artistic skills are really important in presenting your results.”

Then, once students had learned what a haiku is, such as three lines, and the number of syllables in each line, they got a chance to write some. How’d they do?

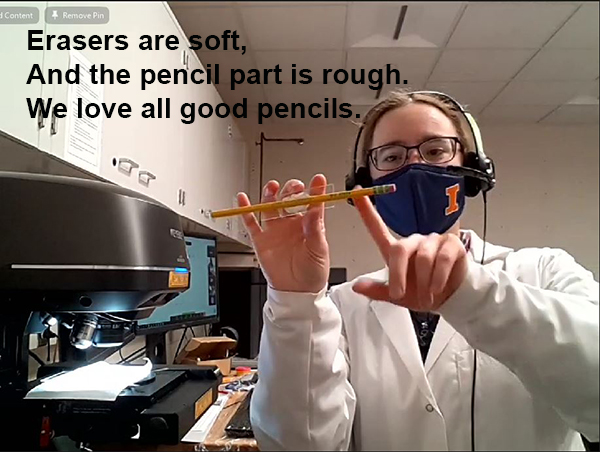

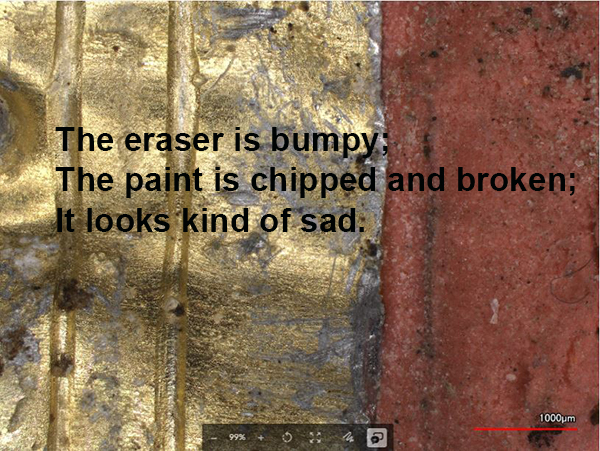

“I was greatly impressed by the quality of the poetry that these students could generate on extremely short notice,” Walsh admits. She reports that there were some “fantastic” poems about pencil erasers, which was mostly what they were looking at in the microscope. She adds that there were also good poems about microscopy, as well as some “really good, deep poems” about life that were only vaguely connected to microscopy. (Note: A number of the students' offerings are scattered throughout this article on various images.)

MRL scientist Kathy Walsh discusses a pencil she's going to analyze under the 3D optical profiler. The Haiku was written by a Franklin seventh grader.

“But they were really good,” she claims. And I was just impressed that in five minutes, they could write such high-quality poetry. And there was some real skill in there. I was just really happy to see what linguistic results were generated. They really had some nice turns of phrase that got it. And it was a lot more than I expected, because I've never taught a language arts anything before.”

Regarding the notion of putting the A in STEAM, Walsh admits, that she had no idea what to expect. “To be completely honest,” she says, “I thought one of two things would happen. Either it would devolve into chaos or they would be completely disengaged. And they would be like, ‘Haiku—what does this have to do with science? Aren't I in a science program?’ So I was really pleased with the buy-in that we got. They just went for it, and there was good stuff out there.”

Regarding integrating science and the arts, while she’s an expert in her field, but acknowledges that she’s not as well versed in language arts. “I'm not an A in STEAM expert,” she admits. “So, I was flattered that they allowed me to do a poetry lesson. But it's all about painting pictures with words. And when you're painting pictures with words about pictures you acquire in a microscope, it just seems very cohesive.”

A haiku written by a seventh grader about a driven-over pencil Walsh looked at via the 3D optical profiler.

So, why haiku? Walsh explains that she’s always liked them because they’re short and therefore easier to write. “I would sit there in graduate school at 3:30 in the morning waiting for a scan to finish. And I would write haiku about my lock-in amplifier because, I mean, what else are you going to do at 3:30 in the morning? It was short enough that it didn't distract me…’cause it was 3:30 and I wanted to go home. So, I sort of got into the habit of writing small little haikus.” (Acknowledging that it “probably sets a bad example to do this,” she also admits, “I used to do that during class taking notes,” when the professor would be going on and on about something.)

Walsh sings the praises of haiku which, although little, provide a big advantage in helping one be precise when writing. In fact, because they’re short, they automatically eliminate wordiness and foster conciseness when writing. “I also feel like since I personally tend to express things in very long and overdeveloped phrases and say the same thing with multiple small variations four times as long as they need to be, I think it's good to practice being concise—sort of “concision” of expression (if concision is a word). That “concision” of expression is a skill I need to practice. At least that's my excuse—that it develops the ability to speak, to say what you mean without going on for three pages.”

Another plus is their form, a first line with five syllables, second line with seven, and third line with five again. Another plus? You get to count on your fingers. “I kept saying, you know, I have a PhD in physics and I still count on my fingers when I'm getting syllables for haiku,” she reports.

Walsh discusses haiku writing during her Thursday afternoon session with the Franklin students.

When considering the many styles of poetry out there, she also figured haiku were something the kids could write in about ten minutes. “I thought, ‘A haiku has a structure. I'd love to give them the freedom to do all these sorts of things, but we've only got 10 minutes.’” She admits that, if left to her own devices, she might have chosen iambic pentameter or rhyming couplets, “which I totally do,” she says. “And when I do that, it goes on for a while. And I don’t know if I could necessarily keep that in 10 minutes.”

While she says the haiku worked out fine, she acknowledges that "A couple of the students broke the mold. They were not going to be constrained by this type format and they wrote their own stuff, but it was good. So I forgive them because it was really good poetry. I was pleased.”

Walsh also figures the little exercise in haiku writing might equip the students for later in their academic careers, maybe even as potential scientists. She admits that being able to express oneself concisely is actually a really useful scientific skill, because journal articles and grant proposals often must be two to four pages. “And if you're inclined to yammer on for three hours about how awesome your thing is, then it's going to be really hard to fit that into two or three pages. And it's a good skill to develop—saying what you mean and not making the reader have to read for a long time.” Walsh claims busy scientists won't necessarily read the thing through, but will often just look at the pictures, read the captions, then “go to the section of the article that actually tells us the specific information we want. And then sometime, if we get time, we'll read the paper.” She asserts that scientists who want people to read their stuff must learn to express the information concisely.

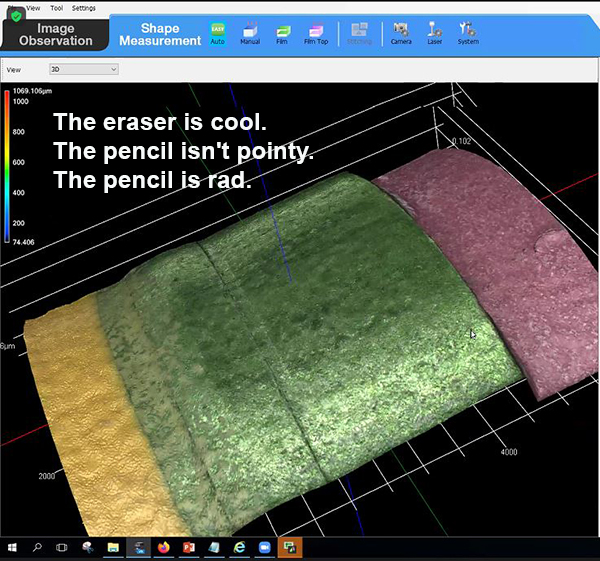

A seventh grader's haiku aptly describes the images of a pencil Kathy Walsh produced via her 3D optical profiler—rad!

Walsh, who never passes up an opportunity to communicate her science to the public, explains where her love of scientific outreach came from.

“I didn't always know I was going to be a scientist,” she admits. In fact, she was specifically interested in history and archeology (actually a science.) “But I was really interested in history, and the humanities, and music, and all sorts of things. I always loved science, but there wasn't a guarantee I was necessarily going to go into science.” So now, she does science for a living and reads history for fun.

She continues: “But if I had gone on another path, I would have done history for a living and read science for fun. So I'm always kind of thinking about the “me” that is out there that took another path, and thinking, ‘I would love to engage with this type of thing.’ And, not everybody should have to do it for a living to be able to enjoy it.”

Her love of scientific outreach also stems from her sense of fairness too; she insists that it shouldn't just be people whose parents are scientists who get to find out about this stuff. “So I really loved the opportunity to talk to people that don't get exposed to it based on what their parents do.”

As far as her participation in the Franklin Musical Magnetism program, Walsh reports that Pamela Pena Martin, I-MRSEC’s Outreach Coordinator “knows I like outreach, and she is very generous, and every time there's an opportunity, she offers it to me because she knows I'm going to be excited about it.”

A variety of different ways Walsh's 3D optical profiler can analyze something, such as a pencil.

Plus, she’s probably invited to participate because the stuff Walsh does is just plain cool! “And also I happen to have the really useful personal trait of having access to instruments that are really good for demonstrations, right?” She admits that she has the good fortune of having “easy access to a microscope that is fast to operate and gives really cool results that are easy to identify with. So it's a natural fit for outreach events.”

On the whole, Walsh was pleased with how the haiku experiment turned out. “I didn't know what to expect from the A in Steam part. And I was marveling…I just had no idea what to expect because I don't really do this on a regular basis.” In fact, she admits that she found it fun. And rewarding.

“It was nice that this whimsy of writing haiku about scientific equipment turned into an actual activity that other people engaged with. It was kind of neat when people followed your whimsical ideas instead of thinking they're really weird. That's gratifying.”

Story by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photos by Elizabeth Innes, unless noted otherwise.

For more I-STEM web articles about I-MRSEC, see:

- Musical Magnetism’s Destroy-A-Toy Activity: Messy, Definitely Curiosity-Driven and Educational!

- Via I-MRSEC’s Magnetic Fields Web Series, Youth Discover Magnetism, Diversity in Science

- I-MRSEC REU Teaches Carmen Paquette a Lot About Magnetism, Research, and Herself

- I-MRSEC REU Exposes Undergrads to Materials Science, Research, and What Grad School Is Like

- Franklin Steam Academy Students Experience High-Tech Science at MRL

- I-MRSEC, Champaign Educator Jamie Roundtree, Embrace Hip Hop/Rap to Reach Youth at Their Level

- Polímeros! Cena y Ciencias Program Teaches About Materials Through a Supper & Science Night

- I-MRSEC: Creating a Multidisciplinary Materials Research Community

More: 6-8 Outreach, Franklin STEAM Academy, I-MRSEC, STEAM/SciArt, Underserved, 2021

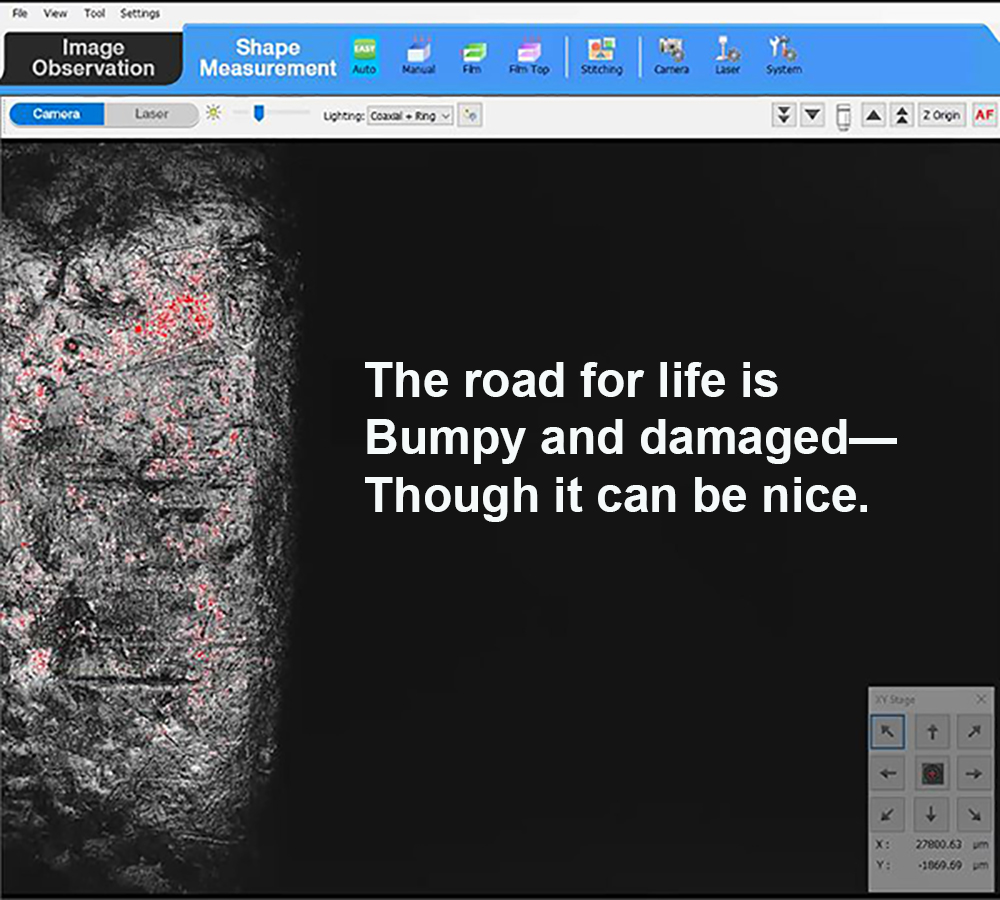

A Franklin student waxes philosophical in a Haiku he wrote. The cool background image is a magnification Walsh made via her 3D optical profiler.

A Franklin student waxes philosophical in a Haiku he wrote. The cool background image is a magnification Walsh made via her 3D optical profiler.

One of Walsh's slides that details how her 3D Optical Profiler works.

.jpg)