Formula SAE: Shaping Engineers Who Think Outside the Box

Front to back: Some leaders of the current SAE Formula team: team captain and president, Mike Bastanipour; Suspension Team leader & main driver, Keith Harris; Alex Allmandinger, Aerodynamics Team leader.

December 19, 2014

It makes sense that three MechSE upperclassmen, senior Mike Bastanipour and juniors Alex Allmandinger and Keith Harris, some of the leaders of Illinois' Formula SAE racing team, want careers in the automotive industry or motor sports. They've spent the last several years designing and competing a high-performance racing car and interning at companies like Ford and Chrysler. But, they've been infatuated with cars since way before that.

For instance, it's been Allmandinger's chosen profession ever since he had an epiphany and resigned himself to the fact that he wouldn't get to be a professional athlete: "About the age of 12, I realized I wasn't cut out for that!" he admits.

Allmandinger sees motorsports as a perfect marriage—joining his love of cars and his love of competition: "I've grown up loving cars, but I've also been very competitive. Motorsports is the one thing that combines the automotive industry with the competition side of things. That drive to get things done on short deadlines, trying to beat other teams, trying to be the best—I think that's what draws me towards motorsports."

Harris' career aspirations are similar. "Definitely something with cars," he says, "since I've been around cars for so long, and it's just kind of become a part of me." He says motorsports has lots of job opportunities: Indy car, Nascar, Formula 1. "There's a lot of need for engineers since all of those teams are trying to improve the cars and win."

And motorsports is why these students chose Illinois.

For instance, Harris recalls that two brothers visited his high school and gave a presentation about SAE. Afterwards, he told himself, "I'm going to do that; I absolutely want to do that." In fact, he was actually considering a school in Austria, but says "the whole learning-German thing made it hard."

Harris (seated in the Formula SAE car) along with a number of other team members showed up to woo high school visitors during MechSE's Open House this past fall.

So with SAE uppermost in his mind, during each school visit he would get a personal tour of the garage and meet the team. Illinois "was a step above and was really pretty impressive," he says. "It was definitely one of the biggest drivers in deciding where to go."

The Formula SAE team (named for their main competition hosted by the Society of Automotive Engineers) is comprised of students from across Engineering, with around half from MechSE. However, their car involves more than just mechanical. An aerodynamics subsystem (comprised mostly of aerospace students) builds the bodywork and works to boost the car's performance. The electrical team (mostly from ECE and Computer Engineering) does the electronics.

But the three believe SAE's interdisciplinary aspect has made them more well-rounded. For example, for three years, Bastanipour worked on the electronics subsystem. (Team captain this year, he's taken on more managerial duties.)

"People usually shop around and choose the subsystem they have the most fun on—whatever interests them the most, not necessarily what they're cut out to do, based on their degree," says Bastanipour. "Because you can learn a lot more when you do that."

Take Allmandinger. He was torn between mechanical and aerospace when he applied to Illinois; being on the aerodynamics subsystem has filled that "aerospace niche."

"The things we're doing are taught in 400-level aero classes: designing foils, designing aero package, a lot of high technicality analysis work," he says. "It's really allowed me to expand outside of the mechanical realm."

While Harris has mostly been mechanical (last year he led the chassi subsystem; this year he switched to suspension), he has another big responsibility: he's the main driver during races.

In addition to exposing members to other disciplines, SAE fills another void: project-based learning: "I think the biggest benefit is the hands-on work that you get to do," says Bastanipour. He says most MechSE courses are theoretical; students don't really build any projects or apply what they learn in class. "The cool part about this is, you take what you're learning in class…and you get to make real stuff with it."

For example, they design something, analyze it (if it's structural, make sure it's not going to break, but can last the whole racing season), figure out how to manufacture it, make it, then assemble it to the car. And integrating their part with what other team members are doing teaches them a real-world skill—cooperating with others.

Bastanipour says, "Just the sheer amount of hands-on work," gives SAE students a jump start on their careers: "All the stuff you'd learn later on in industry, you get to learn here for four years just by joining a team and working on a car."

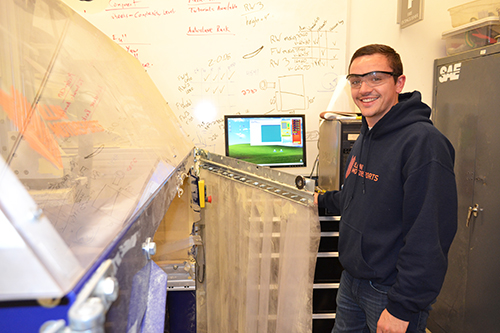

Aerodynamics Team leader Alex Allmandinger shows how one of the machines in their shop, a Shopbot 5-Axis CNC Router, works.

Allmandinger says another benefit is learning how to design something that can be manufactured cost-effectively: "It is easy to design a super intricate part that works really well, but would cost 20–30 grand to manufacture," he admits. But SAE has helped them learn "what's feasible, and what's not."

Harris adds that, on class projects, there's "a pretty notable difference" between SAE versus non-SAE students: "It just puts you miles ahead of the people who haven't had those same experiences."

While two revamped mechanical design classes involve projects (student teams build a contraption to complete in a challenge), "They still don't reach the level of having a really big part on a car and having to do all the steps," says Bastanipour. He equates what they do with senior design: "a lot of work, and going through all the same paces that people on this team do."

Their hard work all fall designing then building their race car pays off—and is tested—in spring at the two big races in which they compete. The biggest one, held at the Michigan International Speedway, is a two-part competition with static (such as business/marketing and design) and dynamic events (such as racing). For one static event, teams design a business and marketing plan for starting a company to make their car and sell it to weekend racers.

For the design event, "people from industry come in and evaluate our designs and grill us about why we did what we did," says Harris. Since Michigan is the home of U.S. automobile manufacturing, judges are from nearby companies: Ford, Chrysler, GM, etc. Harris and Bastanipour, who both interned at Bosch, knew one of the design judges.

"One of my coworkers was a judge who specifically had our team and spoke to us," admits Bastanipour.

So did knowing the judge help the team? Bastanipour's cryptic retort: "It was interesting."

He explains that, rather than giving them points because he knew them, the judge "was a little bit harsher since he expected more out of us." The one perk: knowing the judge made it "more casual, it was somebody we knew that we could talk to, ask questions."

While the guys say Formula SAE is not about the fastest car, they're proud of their accomplishments and keep their many trophies on display.

While the team loves competing—they want to build a fast car and, obviously, want to win—that's not their primary motivation:

"We haven't really lost sight of the fact that it's an engineering competition," says Allmandinger. "It's more about learning than it is about making the fastest car possible. So we could skip a lot of steps and make a really, really fast car, but we would be losing a lot of the whole design process and a lot of learning components for new members."

In fact, they often opt for learning over winning because of financial considerations:

"You can spend money on the best components and all the best parts," admits Allmandinger. "Some of the things we design ourselves, actual companies make, and probably make them better, but they're way more expensive. But just going out and buying a part wouldn't be the same as designing your own, actually going through the whole design and manufacturing process. That's where you learn the most."

So just how much does money come into play? Is there a ceiling on how much teams can spend?

The answer is: no, the sky's the limit. "You could really spend until you ran out of money," admits Bastanipour.

So don't teams with a member whose dad is really rich have an unfair advantage?

The answer is: yes—daddy can foot the bill. "That's how all of racing is," says Harris. "There's always the rich dad who bankrolls people."

But while motorsports may have embraced the old saying, "Money makes the world go ‘round," (or the racing car), the guys say it's a good thing on many levels. For one, the financial incentive contributes to teams' interdisciplinarity…and networking:

"Teams that stretch out from just doing engineering to doing more PR and sponsorship outreach definitely benefit from it," says Bastanipour.

He says teams can spend well into the six figures and "have tons and tons of logos on the car," because one of their goals is to reach out; if they need to make or order a part, they try to get it for free. So, one of motorsport's unspoken rules is, "The more that you can network with people and get stuff," recites Bastanipour, "the better you'll do overall."

Allmandinger says networking can net more than just free parts. Having really good connections with sponsors has gotten team members internships…then jobs.

Then, in a further chicken-and-egg effect, having alumni in companies ensures their getting first dibs on parts. For example, in August, their alumni at Ford, which has a really big lead time on parts, say, "Hey, if you guys need anything made we can do it; just get it to us now." So Bastanipour sends a list of already-designed parts, and Ford whips them up. "So yeah," admits Bastanipour, "it's definitely good to have ins with those big companies that can make stuff for you that we'd otherwise have to pay a lot of money to do here."

Mike Bastanipour displays steering wheel they designed and built.

So, assuming the previous year's car is still around, does the team start over from scratch with their design (and parts), or build on the previous year's design?

The only rule is that the car's structural frame (roll cage) must be new every year (for safety purposes). "But otherwise, you can reuse everything if you want," says Bastanipour, but conscientiously qualifies that with: "I think it would just be a little bit unfair if you took the car from last year and started testing on it immediately. They want you to actually have to build something new."

So every year, SAE's leaders sit down and say, "‘Here's what we want to do better!'" then assign projects and set goals. "I think that's definitely the biggest part of this competition, and how so much stuff gets designed. We want to make it better, and make the car faster, and improve everything," divulges Harris.

One constraint regarding how much to reuse vs. redesign is time. "This is an engineering competition," admits Bastanipour, "so we want to try to push the engineering as far as we can. But at the same time, there's a lot of stuff that has to get done for this car to get on track." So they've had to balance their dream of creating an engineering marvel with reality: meeting deadlines. "That's a big reason we don't remake everything every year," he continues.

"We just don't have the resources to redesign every part of the car every year, so we try to choose parts that will improve the performance a lot and then keep the ones that we know work the same."

Though its members would probably do SAE just for the hands-on experience and the sheer joy of competing, there's an added bonus: course credits.

Freshmen and sophomores take one hour per semester of the "Formula" course, ME199. As students take on more significant roles and workloads (usually around their junior year) they up it to a 3-hour credit, because "a critical part of the car is pretty much under your design control, and so you're going to be spending more time on it," explains Bastanipour. Seniors also take 2 senior design courses; ME470 and ENG491.

Getting class credit is "actually a really nice part of our program here," admits Bastanipour. "It's really rare, especially in competition," and adds that other teams might get senior design credit, but nowhere near as much credit as at Illinois.

"It helps the grades too," he unashamedly confesses. "It helps offset the fact that people spend time here instead of…uh…focusing on their classes 100%."

Another benefit of SAE? Members are practically guaranteed a job.

"We have 100% job placement," boasts Allmandinger. "Every alumni we've had has come out with a full-time job. It's something we're all really proud of, but it also reflects on the work that we do."

And they do work hard. Besides the tons of hours put in during the semester (and Thanksgiving and Christmas break), they've all had internships in industry since their freshman year. "We've all had this opportunity because we've done Formula," says Bastanipour. "We have experience, and we get to have that experience out in industry as well," which gives them insight about what real-world engineers actually do: "I learned a lot about not just engineering," he continues, "but how your degree will actually be applied once you graduate."

Keith Harris changes a tire on the Formula SAE car.

Another benefit of Formula SAE? It looks good on one's resume. According to Harris, companies are looking for students with experience. When recruiters "see Formula on your resume, they prod you for more about that." Online applications for Chrysler and Ford now say: "Formula SAE experience recommended." Adds Harris, "So it's definitely something that is in the minds of recruiters as an important and worthwhile thing to do."

How many students participate in SAE? Because of their focus on recruiting and keeping members, their team has grown over the last couple of years, from15–25 to around 30–40 people who consistently show up and contribute.

Harris acknowledges that the hardest time for students joining the team is the first semester of their freshman year. SAE designs everything in the fall, and the freshmen haven't had much formal coursework. But they can still be involved. "Put yourself out there; start gaining experience and learning about what we do," he recommends. "Second semester, we start manufacturing stuff; that's when they can really get involved and actually make parts that go in the cars."

Allmandinger says lots of things Aero team does are at a higher level technically, but to get more people involved, they break things up into smaller projects. They also train new members on the STAR-CCM+ software used for CFD (computational fluid dynamics), which he says is "pretty technical software to pick up and learn…Aero started using the software for external aerodynamics simulation," says Alex, "but now it's being applied to everywhere else on the car because it's such a powerful tool."

So since team members spend so much time in the shop, do they have time to make friends and do regular college-student-type activities? Bastanipour admits that one of the biggest issues of the team is that all your friends end up being team members. So they try to "meet up and have fun outside of the shop," he says. They started "formula football." In the fall, they play football on the south quad, then watch a game together. They've also done tailgates, bar crawls, and gone go-carting as a team. They hope to attract more freshmen, but also help younger students to get more comfortable with the older people on the team.

Alex Allmandinger prepares to use a Shopbot 5-Axis CNC Router, one of the machines in their shop that they use in constructing their car.

Allmandinger agrees that "Separating the shop from not the shop" has been an emphasis: "It's a little bit easy when we spend 40 hours a week in the same room with each other to get at each other's throats at some points in time." So they've started emphasizing "having time outside of the shop when you don't to talk about the race car or you put it to the side; it helps a lot in keeping things going at the shop as well."

So do the relationships built during those hours and hours spent together in SAE last? Bastanipour says they know alumni who have gone and worked for the same company and are still very good friends: "We spend 4 years here; a lot of these guys, I've spent countless hours working with them at the shop. I've been with them to Canada, Michigan, Nebraska. You spend a lot of time with each other here; I would hope that it transfers on to the future, especially if we end up working next to each other."

To help build the team and recruit, team members also try to find time to visit high schools. Why give up precious Thanksgiving break time to visit high schools? Says Bastanipour: "That's how I was actually recruited for the team."

What's their spiel? Why would highschoolers want join Formula SAE?

Harris cites the experience: "The amount you can learn just working on a small project on the team or being in charge of the whole team of subsystems is so much you won't get in classes. You learn how to network with corporate sponsors, strategize as a team, improve the performance of a high-performance vehicle. There are just so many opportunities that you are going to get that you won't get to do otherwise in your life."

Allmandinger's favorite part is, "You get to build a race car with sponsor's money!" then adds, "We do a lot of really cool things with a lot of really cool materials that we'd never be able to do once we graduate." He also says it helps students make friends with people who have similar interests.

But Allmandinger also recommends SAE because of the career opportunities it opens up: "I think if I was in high school, and you told me I would be working at Chrysler and at Ford and these really cool big automotive companies, I would not even believe you. I would just be, ‘No way; that's so cool!' But now we have options. We're picking between the two. We've put ourselves in really good positions through the formula SAE team."

Harris appreciates the autonomy: "The amount of independence you have when designing things and choosing what to do is way, way, way bigger than anything you'd actually do once you get out into the real world. It's cool to be able to figure out what you want to do, and how you want to do things. I think it breeds a different type of engineer who is more willing to push the boundaries and go outside the box."

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Formula SAE, MechSE, Undergrad Education Reform, 2014

Left to right: Formula SAE team leaders: Alex Allmandinger, Keith Harris, and Mike Bastanipour, with the Formula SAE car, which is covered with sponsors' logos.

.jpg)