Design for America Espouses Human-Centered Design to Solve Unmet Needs

So you try something out and if it doesn’t work, stop doing it. If it is working, make it better and do it more. – Lucas O’Bryan on Design Thinking

May 6, 2019

Aditi Jha interacts with visitors to the Design For America booth at Engineering Open House 2019.

Aditi Jha interacts with visitors to the Design For America booth at Engineering Open House 2019.The goal of the Illinois chapter of Design for America (DFA), according to its president, senior Lucas O'Bryan, is “to create local, social impact through projects that are focused on or partnered with community organizations.” So, through DFA, multidisciplinary teams of students seek to positively impact people’s lives by solving problems using the Human-Centered-Design Process.

The question Lucas O’Bryan kept asking himself pretty much every step of the way during his career in Engineering at Illinois was, “How can I use this to help people?” However, at some point, though he was getting “an awesome technical foundation” and learning “a lot about how to do the hardcore technical stuff,” he realized that what he was missing—what he kept asking himself—was, “‘How am I going to help people?’ because we never talked about people in my classes,” he admits. But then he realized the people-centered focus he sought was broader than just wanting it in individual courses. “I wanted it to be a theme in my entire educational experience in college. That drew me to human-centered design and design thinking. So that’s how I got involved in Design for America.”

DFA is comprised of about 40 students from all over campus: art & design, engineering, business, LAS, etc. These students collaborate on teams that do around 4–6 projects a year to help solve problems for local, community-based organizations. Several organizations DFA partnered with in 2018–2019 included the Champaign Park District, Edison Middle School, and Synchrony Financial and AARP, companies in Illinois’ research park. They also partnered with Clark-Lindsay in Urbana. “Senior citizens were a big focus for us this year and last year, which is really cool,” O’Bryan explains. Regarding their interactions with the seniors at the retirement community, he says, “They were awesome. They were so into it, which is great.”

Left to right: Kirtan Patel, Aditi Jha, and Rajee Shah during a Chicago field trip where a number of DFA members toured firms practicing human-centered design. In this image, the three are brainstorming ideas to improve transportation as an exercise during their tour of IDEO, the biggest leader in using design thinking. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)

Left to right: Kirtan Patel, Aditi Jha, and Rajee Shah during a Chicago field trip where a number of DFA members toured firms practicing human-centered design. In this image, the three are brainstorming ideas to improve transportation as an exercise during their tour of IDEO, the biggest leader in using design thinking. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)Projects DFA is involved with vary, with one thing in common: they’re designed to help people. “I think we’re interested in any sort of project that is making an impact in people’s lives,” he adds.

For example, one project involved a need senior citizens have regarding financial literacy. “So as you transition into retirement, do you understand what’s happening with your finances?” O’Bryan asks, indicating that for seniors, having someone else caring for their finances is an uncomfortable conversation. “So how do we enter that conversation, and then how do we inform, educate people, and empower them to make their own decisions?” he adds.

Another project involved food insecurity among college students, some of whom don’t have access to proper nutrition or are unable to afford a meal every day.

To come up with solutions to these and other problems, DFA teams used Human-Centered Design. We’ve all most likely heard of the engineering process, or the scientific method, but exactly what is Human-Centered Design (HCD) and how is it different from those? According to O’Bryan, “The engineering design process fits that backend for a project. So it’s, ‘How do I build what I need to build, and what do I need to include?’ I think the human-centered-design process provides the why. So, ‘Why am I doing this project?’ ‘Who is going to be impacted by it?’ and ‘Why is it important in their lives?’”

In comparing these processes, he even coins a new word in lieu of compatible: “I don’t think that they’re competitive; I think they’re compatitive!” he exclaims. While he says the engineering process is usually about optimization, he says HCD is more about innovation and creativity. There’s also another difference: The way the two view failure.

“Failure in engineering design is not a good thing,” he admits, “but failure in Human-Centered Design is something that you embrace.” So it’s being comfortable with trying something out—low fidelity prototyping—and if it doesn’t work, you didn’t spend a lot of money on it.”

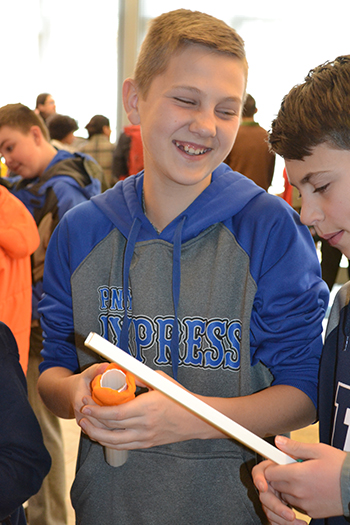

Young visitors to Engineering Open House 2019 learn how to make a low-fidellity prototype at the Design for America booth. DFA's booth won second place for Most Engaging. DFA members at the booth used Mock-Up cards, a game that prompts a user, purpose, and condition to build a prototype.

Young visitors to Engineering Open House 2019 learn how to make a low-fidellity prototype at the Design for America booth. DFA's booth won second place for Most Engaging. DFA members at the booth used Mock-Up cards, a game that prompts a user, purpose, and condition to build a prototype. O’Bryan shares what low-fidelity prototyping is and why DFA is sold on it: it’s simply making a model out of, say, cardboard and pipe cleaners and then asking the user: “Try this out. Does it work? Do you like it?” If their initial response is not, “Yeah, this is great!” but instead, “I wish it had this!"...“You can make that change really quickly!” O’Bryan says. He adds that spending a ton of time on CNC (computer numerical control) machining, milling, or woodworking to cut it out and make it look super nice, “Just takes more time and effort, and if it’s not the right thing, then you’re frustrated because you spent all that time,” he admits.

He also claims that low-fidelity prototypes provide designers with more honest feedback. “If you spend a lot of time making something,” he indicates, “people know that, so they’re less likely to give you bad feedback, even if it’s something that they don’t want. So if you have something that looks kind of cobbled together, a little bit messy, but the idea is there, they’re more willing to be like, ‘I like this part of it. I don’t like this. You need to fix that.’ So you get more genuine feedback.”

Regarding the scientific process, O’Bryan says it’s about making a hypothesis, conducting an experiment, and testing it. “It’s really, really formal. You have to control all the variables. That’s very quantitative.” On the other hand, he calls Human-Centered Design more qualitative. “It’s a little bit more, ‘Let’s just start by trying it and get closer through kind of messing with it instead of formally testing each individual aspect.’”

Design for America members Brianna Creviston and Kirtan Patel run DFA's 2019 Engineering Open House booth, which won second place for Most Engaging. They used Mock Up cards, a game that prompts a user, purpose, and condition to build a prototype.

Design for America members Brianna Creviston and Kirtan Patel run DFA's 2019 Engineering Open House booth, which won second place for Most Engaging. They used Mock Up cards, a game that prompts a user, purpose, and condition to build a prototype.The key component of HCD is communication— really getting to know one’s user. “If you’re designing for senior citizens, for example, it’s not just, Oh, I’ve been to a senior home once. I know what that’s like!’ It’s, ‘I’ve talked to my grandparents. I’m having conversations with seniors that I’ve never met before as I’m going through this project so that I’m more able to better design something that’s actually going to be what they want.’” Assuming that we know what senors want because of one visit to a nursing home isn’t enough. “You have to have those deeper conversations,” he explains. “Yeah, so pushing students to go do that is fun, I love that. It gets people out of their comfort zone.”

And it was because he was not experiencing communication—needs finding—emphasized in his courses, that O’Bryan joined Design for America. “Outside of class, I can learn this skill set to start to kind of develop it, and then it is just going to make me a more well-rounded person.”

In addition to Human-Centered Design, another tenet of DFA is its multi-disciplinary emphasis. Comprised of a broad spectrum of students from all across campus, DFA fields very multi-disciplinary teams for projects, comprised of students from, say, Art and Design, Chemistry, Engineering, and Finance, working side by side. This ensures that DFA members become well rounded and comfortable with working on multidisciplinary teams and not necessarily having all the answers themselves. But suppose one team’s project is about finance. How does DFA keep students from other disciplines engaged, since the problem of the project they’re assigned to isn’t particularly related to their discipline and thus doesn’t tap into a student’s knowledge, skills, and abilities?

Left to right: Lauren Cox, Allastair Merrett, Annabelle Huber, and Sneha Subramanian doing a retrospective with Pixo, a design consultancy in downtown Urbana. All DFA teams visited Pixo instead of weekly all-studios to get help reflecting and strategizing during the build/test phase of their projects. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)

Left to right: Lauren Cox, Allastair Merrett, Annabelle Huber, and Sneha Subramanian doing a retrospective with Pixo, a design consultancy in downtown Urbana. All DFA teams visited Pixo instead of weekly all-studios to get help reflecting and strategizing during the build/test phase of their projects. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)This scenario is something the DFA Executive Board actually addresses during recruiting interviews. “We’re really looking for people that are curious and going to take the time to learn and explore new things,” O’Bryan explains, indicating that one tenet of DFA is: “You’re constantly learning, leaning on other people and their expertise.” To foster this, teams are intentionally not comprised of people from the same major. So the whole DFA experience of addressing a problem not necessarily related to one’s field causes its members to learn a lot from the other members in other disciplines. In addition, teams constantly refer back to the users, the people they’re designing for. In the end, “They’re the experts,” says O’Bryan, “’cause they know what their experiences are like.”

Regarding this principle, O’Bryan describes one project his sophomore year. It was right before the last presidential election, and they were looking at echo chambers on Facebook. “You see a lot of stuff that you agree with, right?” he says. And this stuff kind of reinforces your beliefs. However, one person on his team, an architecture major, brought up how built environments can change the way people have conversations. So the team brainstormed about a pop-up to foster dialog about different topics between Democrats and Republicans. The goal wasn’t for folks to leave in agreement, but to leave understanding that others have different points of view.

“People just don’t know that other people have a different point of view because their echo chamber of Facebook keeps showing them the same thing. Right? So being exposed to those different perspectives, regardless of whether you agree or not, is good.”

In fact, O’Bryan, a pretty liberal Democrat, went to some Republican meetings during that time period. “It opened my eyes to: ‘Hey, I don’t disagree with all of this. There’s common ground that we can have, and we can have conversations, and sometimes we can’t, and that’s hard.’ How do you navigate that? So for me it was a really good experience.

For O’Bryan, that particular project brought him back to what he considers to be the most fundamental part of human-centered design: “Empathy. Being able to say, ‘We have disagreeing opinions on some things…but that’s okay. You’re still a human being, and I can care for you. And I know that we may have different approaches for how to address helping poor people, but we both want to help poor people.”

Though they didn’t actually build their pop-up, O’Bryan learned from it personally. “Just that experience of thinking about built space in a different way was awesome. And I wouldn’t have had that had I not had an architecture student on my team.”

Like its multidisciplinary teams, DFA’s Executive Board itself has people from all across campus too. As President this year, O’Bryan, a Materials Science & Engineering major, calls his role the “big picture stuff: understanding what DFA is, who we are, and being able to make connections across campus and the community.” Thus, O’Bryan and the other leaders have been grappling with the following: “What is Design for America?” “Who are we trying to recruit?” and “What are the types of projects that we do?” Once they answered those questions reassessing DFA’s current status, they restructured the Board to properly reflect that. “So that was a big kind of transformational conversation that we had this year,” says O’Bryan. He also facilitates connecting the chapter with the national DFA network, including alumni who’ve graduated from other universities and are now in different companies and organizations.

DFA VP of Operations, Kirtan Patel, (right) and Brianna Creviston interact with young visitors at Design for America's 2019 Engineering Open House booth, where visitors were encouraged to make low-fidellity prototypes.

DFA VP of Operations, Kirtan Patel, (right) and Brianna Creviston interact with young visitors at Design for America's 2019 Engineering Open House booth, where visitors were encouraged to make low-fidellity prototypes.Another Executive Board member is the VP of Operations, Kirtan Patel, a Chemical Engineering major and a Business minor, who does planning and logistics, such as room reservations, the nonprofit finance paperwork. Patel, along with Forest Lam, the VP of Professional Outreach, helped to spearhead DFA’s officially becoming not just an RSO, but a nonprofit, which allows partners to more easily donate money to support projects. Lam, a Civil and Environmental Engineering major, also connects with companies who sponsor DFA , “I would be completely insane if I didn’t have Kirtan and Forest,” O’Bryan admits. “They keep me accountable for all of that.”

Another Board responsibility is recruiting new members, headed up by the VP of Membership, Aayushi Patel, a Molecular and Cellular Biology major who hopes to become a surgeon. She plans membership events, social events getting people together, and “making us a student organization that people are proud to be part of,” says O’Bryan. DFA recruits more heavily in fall to prevent student turnover for year-long projects, then again in the spring for semester-long projects. One recruiting strategy that has been a huge success has been their emphasis on Design in certain disciplines: for instance, Design in Education, Design in Engineering, Design in Healthcare, Design in Urban Planning, etc.

O’Bryan shares how design could be helpful for, say, education students with their lesson plans. “If you’re thinking about how do you improve your classroom experience from year to year, you talk to your students. ‘What worked? What didn’t?’ You ideate a bunch of solutions to that. So you come up with a bunch of different alternate lesson plans and then you prototype it out. So instead of totally revamping all of your lessons, what’d you do is try something new in class one day, and if it works, you do more of it. If it doesn’t work, you just stop doing it, and then you just kind of build on it.”

During DFA's recent, end-of-the-year Expo, Declan Glueck (right) explains to a visitor about her team's project: how to boost intrinsic motivation in students at Edison Middle school. Her team's final marble jar and teacher bingo prototypes integrate into several existing systems in Edison and are being tested by the school board. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)

During DFA's recent, end-of-the-year Expo, Declan Glueck (right) explains to a visitor about her team's project: how to boost intrinsic motivation in students at Edison Middle school. Her team's final marble jar and teacher bingo prototypes integrate into several existing systems in Edison and are being tested by the school board. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)The idea is for students from different disciplines to use the same problem-solving process DFA employs for its projects to connect to one’s professional workspace. “What I just described is nothing earth shattering,” he admits. “It’s not crazy new, but it’s just getting people to be comfortable in doing that, because I know a lot of teachers who will teach the same thing for 20 years. And so we’re trying to get people to be more comfortable being agile and explorative and trying something new, even if it doesn’t work. So failure’s okay; be optimistic about the change that you can make.”

New recruits are immediately placed on projects, which O’Bryan calls: “Trial by fire—so we kind of throw them right into the project, and have them learn as they go.” DFA also provides more formal education on HCD steps during weekly meetings. But he envisions more robust new member training in the future. “It’s been really interesting to see what things need to be put in place before other things can happen,” he says, regarding insight he’s gained as a leader of DFA.

The Board member who works most directly with teams is the managing co-director: Angela Chan, a Systems Engineering & Design major. She provides HCD education and helps teams who are hitting roadblocks or having communication issues with community partners. Chan will be succeeding O’Bryan and taking on the position of President for the 2019-2020 school year.

The Board also includes Jane Chun, VP of Marketing, a Graphic Design major with a minor in Informatics, who does DFA’s Facebook, Instagram, social media, website, visuals, and flyers.

Left to right: Lauren Nortier and Rajee Shah at DFA's last all-studio meeting where the Board asked for feedback on projects, events, membership, and design-thinking education to start planning for next year. Members put up criticisms and ideas around the room to help the exec team reiterate to improve DFA. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)

Left to right: Lauren Nortier and Rajee Shah at DFA's last all-studio meeting where the Board asked for feedback on projects, events, membership, and design-thinking education to start planning for next year. Members put up criticisms and ideas around the room to help the exec team reiterate to improve DFA. (Image courtesy of Jane Chun, DFA's VP of Marketing.)Executive Board members practice what they preach regarding Human-Centered Design; they don’t just champion it for external projects, but use it to improve DFA itself. “It’s funny,” O’Bryan admits, “the Executive Board’s project is Design for America itself. So we’re using the same process that we’re teaching people…We’re constantly talking to people in the organization. We come up with something, present a concept, and then iterate on it.” Two things DFA hopes to change down the road include a new member education program, and putting more structure into timelines for projects.

So has DFA ever had a member who started out majoring in a certain discipline, but because of his or her experience, completely changed the trajectory that they were headed? Yes, O’Bryan himself actually!

He joined his sophomore year planning on doing very technical engineering stuff in industry; now he’s thinking about doing graduate work in social work, with a career goal of doing higher-level legislative work with nonprofits. “So it’s a big shift for me personally,” he admits. “It came down to realizing that, yes, I’m good at the technical and, yes, I’m good at the math and science, but at the end of the day, what I care about, what is fulfilling for me is conversations with folks and seeing the impact that I can have on people’s lives.” While engineering has given him a great foundation of being able to think critically and break down problems into smaller parts, he’s excited to expand his skill set into community outreach and legislative impacts. In the immediate future, O’Bryan will be at the Seibel Center for Design full time next year, working on projects, and helping out in courses.

How has O’Bryan benefitted from Design for America personally? “I think it’s shown me that engineering can be more than the technical,” he explains. Plus, it’s also provided community.

“I think for me personally, it also introduced me to people who were creative and want to make a difference in the world and were empathetic and wanting to work on projects. I think it was just as simple as getting connected with those types of creative, empathetic people. So on campus and, then, also nationally, the biggest thing that it’s done for me is show me a group of people who are doing things that I’m excited about and want to be involved in, and then are supporting the things that I want to do.”

Story by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photographs by Elizabeth Innes, unless noted otherwise.

For aditional I-STEM articles about Design for America, see:

More: Undergrad, Student Organizations, 2019

.jpg)