VInTG IGERT Inspires Ph.D. Student Lynette Strickland to Choose a Career in Research

May 2, 2016

Ph.D. student Lynette Strickland and member of the VInTG IGERT in her office in Carla Caceres' lab in Morrill Hall.

How did a little girl who had never been further than her home state of Texas and dreamed of being a veterinarian end up a researcher at Illinois, who also spends large blocks of time in Panama and is passionate about studying, in particular, the colorful Chelymorpha, or tortoise beetle? Lynette Strickland, an Animal Biology Ph.D. student who works in the lab of Illinois researcher Carla Caceres, credits the NSF-funded VInTG (Vertically Integrated Training with Genomics) IGERT.

Even when she was little, Strickland was obsessed with investigating living things. “My mom tells me stories how she would walk me to the bus stop to go to school,” admits Strickland. “We’d have to leave 15 to 20 minutes early because I would have to look at every flower and every butterfly and every ant hill. So I think it’s just something I know I’ve always loved and appreciated.”

In fact, it was her love of biology—animals in particular—that started her on her current career path. How long has she loved living things? “Since I was four years old,” she says. “All my life. Although, I thought I wanted to be a veterinarian for the longest time. I think that’s what got me along the way into college. I knew I had to go to college to be a veterinarian.”

Knowing how passionate she is about living things, you can imagine how thrilled she was to discover, as an undergraduate student, that she could actually have a career studying them: “It was a couple years into my undergrad,” reports Strickland, “that I found out about graduate school and life as a researcher and that you could actually make a career of studying life. That just blew my mind. At that point, I was like, 'That's what I'm going to do!'”

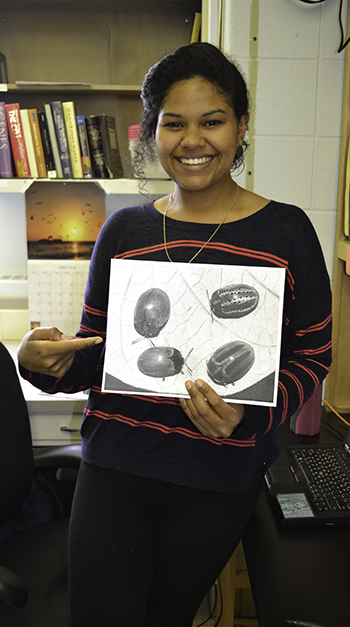

Lynette Strickland exhitbits a photo of Chelymorpha, or tortoise beetles.

So Strickland, who grew up in Austin, Texas, and, in fact, had never left Texas before, found herself interviewing at the two graduate schools in the Midwest that she was trying to decide between: Illinois and Indiana. She reports that the many benefits of the VInTG IGERT quickly swayed her towards Illinois. “Ultimately, I was funded better here,” she admits. “IGERT is a really great funding source for the student. Two years fully funded. This is what allows me to work for 6 or 7 months in Panama, when otherwise I would be here teaching.”

So not only is VINTG paying for two years of her Ph.D. program, but it is covering an all-expenses-paid trip—twice—to the steaming jungles of Panama, a hot spot for all kinds of insects.

Strickland says that the first part of the VINTG IGERT was a 4-week course done in Panama. During the course, students were introduced to approximately 40 staff scientists, plus numerous different interns, fellows, and volunteers. In addition, she and her cohorts visited six or seven different areas around Panama with these staff scientists.

It was there on her first trip to Panama during the spring semester of 2015, that she met the love of her life—the Chelymorpha beetle, commonly known as the tortoise beetle. She explains that she was on a trek through the jungle with Don Windsor, researcher with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute who is one of her Panama mentors, when she first spotted the tortoise beetle up close:

“We had been hiking maybe at least eight hours. It was about 5 or 6 PM at this point. We started at something like 7:30 AM. He had told me about these beetles, and I was like, ‘I really want to see one!’ So I finally managed to flip over a leaf on the ground and on the other side of it was this beautiful beetle, and I was taken right away. Right away. Fell in love. That’s exactly what happened.”

Strickland wandering through the jungles of Panama looking for Nephila spiders for her predator trials.

(Photo courtesy of Lynette Strickland.)

Strickland says her research is specifically targeting diversity, “how diversity is formed and maintained. I’m using beetles to look at the color variation that they display, and how this color variation is formed and maintained.”

This writer recalls a past lesson about natural selection among a certain moth species, where black moths, camouflaged against the bark of the black tree they preferred as a food source avoided detection by birds, while the white moths, who starkly stood out against the tree’s bark, were easily picked off by birds, thus decimating the population and causing the color shift to black in the species. Does this sort of thing come into play with her beetles?

“That’s one thing I’m looking at with my ecology studies,” acknowledges Strickland. “I’m looking at whether predators preferentially eat one of the different phenotypic variants of the beetles, or if they preferentially avoid one of the color variations of the beetles.”

Ironically, while one might assume that brightly colored insects would be more easily picked off by predators, as in the case of the above moths, Strickland says this is not necessarily the case.

“So, especially in the tropics, and with insects, a lot of times they’re brightly colored because they’re sort of advertising, ‘Hey, I’m distasteful or I’m toxic.’ So like the poison dart frogs, that’s one reason why they’re so incredibly colorful is that it’s easier for predators to remember them, and say, ‘That tastes bad; avoid it!’ So it’s really cool!”

Four Chelymorpha, or tortoise beetles. Photo courtesey of Dr. Donald Windsor, Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute scientist.

Knowing that this color-related adaptation exists, she reports, “I’m trying to look at it to see if my beetles get that same response from predators.” Her beetles are variations of red, black, and metallic. “So they are gorgeous!” she brags. “They just stand out. You’ll see them on a green leaf and they just stand right out.”

Strickland isn’t just considering the impact of color, but a number of other factors. “What we can learn from this sort of research is how the environment—the ecological factors, predators, other individual beetles, whether there’s sexual selection acting on them, whether there’s something to do with physiology, if a certain color variant is able to reproduce better in more environments. Taking all of these environmental and ecological factors, and also looking at genomic factors. So what areas of the genome are contributing to the differences in color that we’re seeing?”

Strickland adds that, via the VInTG IGERT, she has had access to a diverse team of researchers, both from Illinois and the Smithsonian, who have expertise in all these aspects of her research: “It was really great to have a team that advises me on the ecological aspect, and a team that really advises me on the genomic aspect.”

Strickland’s love affair with the tortoise beetle hasn’t always been smooth sailing. She tried to raise some in the basement of Morrill Hall, but, due to lack of sufficient humidity, they went the way of the fish many of us tried to raise as children. However, according to Strickland, the demise of her subjects has a silver lining…in order to complete her research, she must work for long stretches in Panama, where there is lots of heat and humidity, and, therefore, an abundance of tortoise beetles.

Another silver lining, this summer, her family, none of whom have ever been out of the states, are going to visit her.

“My family is actually going to come visit me in Panama this summer, and it’s going to be the first time that they’ve left the country. To be able to bring this to full circle and have my family come, my mom in particular, means everything to me.”

Strickland’s advice to the fam: Take plenty of sunscreen and insect repellent, and wear loose clothing that doesn’t stick to your body because of the heat and humidity.

Strickland (right), who works with kids a lot in Panama, shows off her beetles to one of the children in Gamboa, the Panamanian town in which she lives when in Panama. (Photo courtesy of Lynette Strickland.)

What are Strickland’s career goals? She wants to work at a university. “I would love, love, love to be at an R1 institution (a Research 1 institution, like the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign) somewhere. I really like the advisor aspect. I want to be mentoring students. I really like the teaching aspect. It’s one of my favorite parts—sharing the cool results that you found. And of course, I really love the research aspect. So just, in general, I think an R1 university would be a really great place for me.”

According to Strickland, the opportunities afforded her via the VINTG IGERT have changed her life. What has it meant to her?

Ph.D. student Lynette Strickland uses a microscope in her lab in Morrill Hall.

“That’s hard to put into words. For me personally, I could never quite put a price on what this has been to me. I came from a low income, single-parent household. I was the first person in my family to go to college. Before I interviewed here and Indiana, those were the first times I ever left Texas. Then, a year later, I was spending seven months in Panama working with the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute with brilliant staff scientists, and meeting some of the brightest students I’ve ever gotten the chance to talk to.”

Strickland also acknowledges that the interactions with people she’s gotten to work with as part of the VInTG IGERT have shaped who she is as a researcher and essentially determined her career path:

“We just had such diverse interests—everything from people, to insects, to mammals, to manatees. Just so many different things, and so many different conversations that I was able to have, has just done so much to really form me over the past couple years. To really form my research interests, who I want to be as a scientist and a researcher, who I want to represent. This IGERT fellowship has meant the world to me.”

Following is an article written by Lynette Strickland and colleagues about their experiences as minority students, which was recently published in the Science journal: Without inclusion, diversity initiatives may not be enough: Focus on minority experiences in STEM, not just numbers

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

For more related stories, see: Biology, Funded, Grad, IGERT, Student Spotlight, Underserved Students/Minorities in STEM, Women in STEM, 2016

For additional istem articles about the VInTG IGERT, see:

Ph.D. student Lynette Strickland in her lab in Morrill Hall.

.jpg)