MCB’s Jeremiah Heredia: Passionate about HIV-1 Research, STEM Outreach to Underserved

February 8, 2018

Molecular & Cellular Biology (MCB) PhD student Jeremiah Heredia.

Jeremiah Heredia hasn’t always been as passionate about science as he is now. In fact, as a kid, he didn’t like it one bit. “Not at all,” he admits. “I wasn’t into science at all!” Actually, he wanted to be a baseball player…a second baseman, to be precise. Nowadays, however, instead of pulling on a baseball glove, the fourth year Biochemistry PhD student is pulling on lab gloves. But he’s still competitive. However, instead of trying to beat an opposing little league team, he’s moved on up to the big leagues and is going after an even bigger W. He hopes to beat some of the major diseases plaguing our society, like HIV-1, for instance. And when he’s not in the lab, he’s out doing something else he’s passionate about…getting underserved students excited about science.

Of the work he and his teammates in Erick Procko’s development lab do every day, he modestly claims to be “playing a small role” in coming up with a vaccine for HIV-1. He says they’re “trying to come up with a method to get several thousands of mutations from one experiment in human cells.” According to Heredia, their work could be useful for finding cures for a number of diseases; eventually, he and his colleagues hope to say to the scientific and pharmaceutical world: “Now, here’s an example of what you can do in this method.”

Learning all about diseases fascinates Heredia, and he particularly relishes the challenge of finding a cure: “I like science, and I like diseases; that’s what got me into science,” he says. “You find out that someone has a disease and, with science, you get to learn about the disease and then you try to find out how we can cure it. If it's any sort of disease, it becomes tangible for me, I can see it, and it's easier to study.”

Heredia interacts with STEAM Studio participants during an MCB outreach.

In fact, Heredia intends to spend the rest of his life studying them, and he probably won’t have to worry about job security either.

“I'm going to be in science for life because, unfortunately, diseases are still gonna’ be with us, and I want to make a difference. I really did not know much about HIV-1 until I got into this lab, and it wasn't until a year and a half ago that I really got into this project. And I like it. Ideally, I would love to stick with the HIV-1 field.”

So how did Heredia go from not liking science at all to eating, sleeping, and breathing it? He met a scientist who looked and sounded like him. And for him, a Hispanic who grew up in a low income area in San Jose, California, seeing someone who looked like him doing science was key.

“Growing up, the people who were doing science weren’t like me. They were just different from me. So I never gave it a second thought."

So Heredia had no idea what to study when he went to college—no idea what he wanted to choose as a career. He loved math, and always though he’d do something with that. So did his high school counselor. On noticing that he was doing well in it, she asked Jeremiah, “So you like math? When Jeremiah answered, ‘Yea,’ the counselor advised, “So be an engineer.” Jeremiah wasn’t sure that appealed to him (“That part of my brain wasn’t there,” he acknowledges), but he knew that there were different kind of engineers, so he asked, “Could you give me examples of what type of engineer I should be?" The counselor replied, “Just go for any engineering; you’ll make a lot of money, and you’ll be happy.

So Heredia dutifully followed her advice and was admitted to San Jose State in general engineering. As fate would have it, one of the requirements was chemistry, and Heredia immediately fell in love.

“I did,” he acknowledges. “I did. It was weird. For the first time, there was a course I could really see myself doing.”

So he marched into Professor Seamaster’s office and told her that he loved her class and wanted to switch majors, to which she replied: “You are crazy! So you took one semester in this course, and you want to change your whole life?” She advised, “Don’t do that. If you’re really serious about it, take the second course…If you still like it, come back and talk to me.”

So he did. He took the second course, did well in it, still loved it, and went back to chat with her again.

Realizing that he was serious, "She told me all the possibilities I could have,” he recalls. This conversation was pivotal in terms of his career deliberations. But what had an even bigger impact on him, even more important than the words she spoke, was the fact that she was also an underserved minority—someone with whom he could identify.

MCB graduate student, Jeremiah Heredia, interacts with a local elementary student at STEAMcation.

“I remember that was the first time I could talk to anyone who was similar to me and into science,” he recalls. “That was the first time I saw a career goal. That moment really stuck with me. That's a big reason I like helping with these events, because I never really had anyone help me out. I really felt fortunate I ran into her. If not, I would not be doing this."

Fast forward a few years, and for his Master’s, Heredia attended Cal State, LA. By then, he knew what he wanted to do—biochemistry—and was focused.

“I had no direction before; now I do have a direction, so it’s easier now,” he admits.

So how did Heredia, a California boy born and raised, end up at Illinois, with its capricious Midwestern winters? He felt the need to get away and concentrate solely on science and his career

“I wanted to come and challenge myself,” he acknowledges. He confesses that as an undergrad, he didn’t do as well as he wanted to in school, which was partly because he stuck around home, when he needed to get away. “As much as I loved everybody there, I just had to put science as my number one priority. The best way to do it was to get out of town. As much as I love my friends and family, for this period of my life, I just had to take it seriously."

Heredia at his desk in Erik Procko’s development lab .

So he enrolled at Illinois, where he’s now doing cutting-edge research on diseases. Has he ever regretted it? For the most part no. He claims it’s been great “experiencing a whole new life.” He’s gotten the chance to interact with people who are not only from all over the U.S., but from all over the world. And as a member of the MCBees, the MCB Graduate Student Organization, he’s with people who “want to connect with each other but also want to be involved in something.”

“It’s nice that I have found a bunch of people who are similar to me but they’re different enough that I'm learning from them," he says.

He joined the MCBees for two reasons. One, it’s a place to belong. “Being with the MCBees is easy. It’s easy talking to fellow students outside of the lab. It’s such a different dynamic I have with them.”

His second reason is for the outreach. Though he acknowledges that he and his fellow MCBees volunteers have “gotten much closer because of it,” he doesn’t volunteer for the social benefits. He hopes to get undeserved kids into STEM—to have an impact on young minority students similar to the impact Professor Seamaster had on him. So he’s helped out in numerous MCBees outreach events. “It's always in the back of my mind,” he says. "If I can help out, I help out."

Having encountered Heredia at numerous outreaches, this writer was tempted to say, “He’s never met an outreach he didn’t like,” but that’s not actually true. When it comes to outreach, Heredia is somewhat persnickety, and shares this caveat: “If there are kids who are really set on it [science], I'll help them out, but they’re set on it and they’re gonna’ do it. Whereas I want to show science to the ones who may have never seen it before.”

MCB grad student, Jeremiah Heredia, works with UHS student athlete Akierra Bufford who is learning how to use pipette in order to do the DNA hands-on activity.

He shares this anecdote: he had volunteered one time at the MCBees’ monthly outreach at the Orpheum Children’s Science Museum, and decided it wasn’t for him. He recalls that a lot of the participants were kids of faculty members. “So the kids already knew so much, and they were telling me stuff I didn't know. I felt like, in that case, my time wasn't being effective. These kids were already well on their way to science, and there was not much for me to do.”

Heredia has particularly enjoyed I-STEM’s outreach events with the Urbana High student athletes. “I loved it, he concedes, “because I could talk to them as a fellow athlete. I know that they’re competitive and that they like to do well. I would try to be competitive with them but also encourage them. I would tell them 'Oh, you can pipette and learn these experiments!' The students I was talking to were pretty engaged, and it felt good. I felt like they did appreciate me being there."

Heredia believes they could not only identify with his being an athlete, but the fact that he’s a member of a minority people group. He says it’s important for undeserved kids to see someone who looks like them doing science.

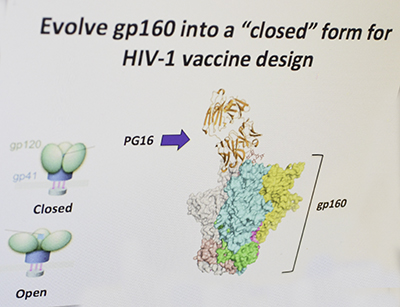

A slide explaining the HIV-1 vaccine design.

"For me, it was huge,” Heredia admits. “It wasn't until I saw that professor that I thought I could do this. She talks like me, and the connection I had, I could see myself doing this. Before, I always had this image of, ‘If you're in science, it’s because you are automatically smart and you know you want to do science.’ Everyone I saw, wasn't who I was. I thought, ‘Why should I try it?’ And there are probably other students who are like that too. If they see someone like me, they might think that they can do this too.”

What is it about research that he finds so intriguing? He says that at first, it’s about learning the technique; then after that, it’s the challenge. “After that, it's fun,” he admits.

For Heredia, the challenge is part of the fun. And the challenge he's currently having fun with is working with mutating HIV-1 which changes from an open to a closed form. “The fun part is trying all the different ways to solve this problem,” he acknowledges.

He also says that while there’s nothing like the emotional high of a major breakthrough, those don’t come often. He admits this about research: “It does get frustrating after many failed attempts. That part is tough,” but adds that researchers must help to buoy each others’ spirits. “If you surround yourself with good people, you can’t help but be happy. I'm lucky in my lab that we're all good to each other. We all have those down moments, but then we pick up each other."

During the I-STEM Summer Camp MCB Day. grad student, Jeremiah Heredia explains a procedure to UHS student athletes.

He also adds that it helps to be an inherently optimistic person: “You have to be optimistic, because you're gonna’ fail a lot more than you succeed. But when you get that success…” He admits that another strategy is to take a short break from the big project and work on a small one that you know will be successful.

What are Heredia’s goals for the future, once he gets his PhD?. He doesn’t want to be a faculty member; he just wants to be in the trenches doing research. And while he’s really into HIV, and feels that in some ways, doing some other kind of research would be a waste, because he’s learned so much, he’s also realistic and knows that he needs a job. He would be happy with any biomedical research facility…maybe Genantech, in his home area.

While Heredia appears to be firmly entrenched in his life’s dream of researching diseases, is there any chance he might return to his first dream, playing baseball? Probably not.

“Once they started throwing curve balls, I was done,” he admits, “’cause the ball was coming at me!”

Story and photographs by: Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

For more related stories, see: MCB, MCBees, Student Spotlight, Underserved Students/Minorities in STEM, 2018

For additional I-STEM articles about MCBees and the work they've done previously, see:

- MCBees Use “Whodunit?” to Pique UHS Students’ Interest in Science During I-STEM Summer Camp

- Illinois' MCBees Expose STEAM Studio's STEAMcation Students to Medieval Science

- MCBees Help Provide Student Support, Recruit, & Share the Joy of Science

MCB grad student, Jeremiah Heredia, works with UHS student athlete Akierra Bufford.

.jpg)