Cena y Ciencias—Science Demonstrated in Spanish by Hispanic Role Models

March 11, 2020

“We use language as a powerful tool to connect with the communities and provide an example for the children.” – Felipe Menanteau

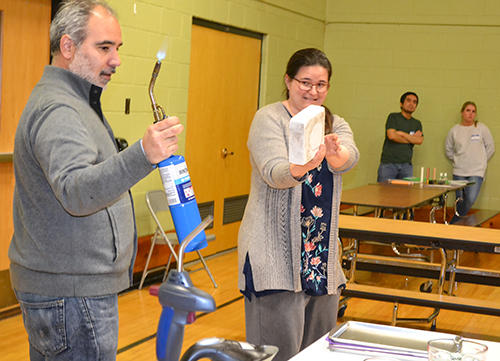

Felipe Menanteau teaches the youngsters at Cena y Ciencias about heat and temperature.

Pizza. Exciting demos (including one featuring a blowtorch!). Hands-on activities related to temperature. These are some of the fun things a group of Kindergarten through 5th graders from two Urbana elementary schools, Dr. Preston Williams and Leal, experienced at Cena y Ciencias (Supper and Science) on March 2nd. The evening at Williams was comprised of supper (pizza) followed by science, of course. The night’s theme was: “Put to the Test of Fire: Materials That Protect Us.” However—probably most important of all—the night’s activities were all conducted in Spanish by scientists of Hispanic heritage.

Cena y Ciencias (CyC) is a Spanish-language science outreach program for two dual language program schools held monthly at Williams throughout the fall and spring semesters. CyC partners include the Illinois Materials Research Science and Engineering Center (I-MRSEC), NCSA (the National Center for Supercomputing Applications), the Center for the Physics of Living Cells (CPLC), the Illinois chapter of the Society of the Advancement of Chicanos and Native American Scientists (SACNAS); Urbana School District, Champaign Unit 4 School District, 4-H, as well as parents from those schools. Moreover, the National Science Foundation has been a source of support for the program since its inception.

Faculty and researchers from the above University partners and from a variety of disciplines across campus, including Astronomy, Chemistry, Materials Research, Engineering, and others, help with lesson content, developing ideas and concepts to be communicated, plus demos and hands-on activities to underscore principles being taught. Helping with activities and serving as role models are Spanish-speaking students who are passionate about science outreach.

Paul Ruess places a few drops of water on a youngster's hands during an activity.

One driving force behind CyC, both in curriculum planning and implementing the program, is Chemistry Associate Professor Joaquín Rodríguez-López, who characterizes CyC as a community. “CyC is truly a group activity, and it works so well because of the engagement of all involved, from the student volunteers from the SACNAS chapter, to the university staff, the teachers and staff at participating schools, the PI’s that learn how to better explain their science, and all the members and invited scientists that design and test the experiments. It’s strength in community. We are also extremely grateful to the institutions that allow this to happen, these are manifold, and in the specific case of my laboratory, support from NSF is crucial.”

Serving as the supervisors for Cena y Ciencias are Mariela Saenz, the coordinator for the Urbana programs, and Lina Florez, the coordinator for the Champaign programs. A senior in Astronomy and Physics, Forez is also part of the BESO (Bilingual Engineering and Science Outreach) program at CPLC. According to Florez, the CyC theme for the 2019–2020 school year has been Salvar El Mundo (saving the planet). The idea behind the March 2nd lesson was to help the kids understand the difference between temperature and heat. It addressed the thermal properties of materials, flame resistant materials, and new ways to apply materials to protect people.

Felipe Menanteau and Pamela Pena Martin prepare to do a blowtorch demonstration about high-temperature-proof materials used in space shuttles.

Starting the evening off with a bang was Felipe Menanteau, an NCSA research scientist and Astronomy Research Associate Professor. Menanteau’s eye-catching demos addressed the difference between heat and temperature, and how different materials react to/behave with heat.

Usually, an adult leader presents CyC demos, with children seated a safe distance away and not necessarily interacting with or touching anything. I-MRSEC outreach coordinator Pamela Pena Martin claims the goal of the demos is to be “very showy” and to “WOW” the kids. Filling the bill on March 2 was a demo performed by Menanteau and Pena Martin: he wielded a blowtorch, aiming it at some heatproof, fire-resistant materials she held in front of her. This demo was demonstrating heat-resistant properties in materials, such as those used to shield space shuttles to protect them on reentry into earth’s atmosphere, for instance.

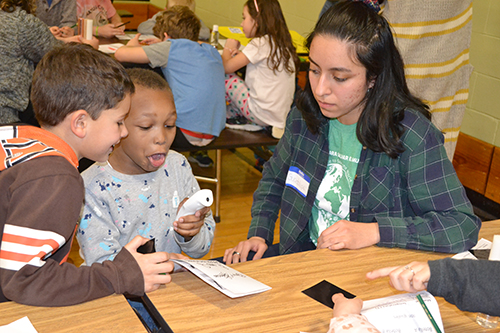

Next, youngsters participated in several hands-on activities addressing the theme of the night. These activities were geared toward different age groups: younger kids (K–2nd graders, 5–8 year olds), older kids (grades 3–5, ages 8–11), or the whole K–5 range. In the first hands-on activity, the kids were using different tools (their hands/senses, an aquarium thermometer, and a digital thermometer) to measure the temperature of three different rods, made of copper, plastic, and wood. The second activity involved kids rubbing some liquid from two different bottles on their hands: one bottle contained hand sanitizer, the second, water. After having a little liquid placed in their hands, they were to either blow on them or wave them around. Blowing on their hands after applying the hand sanitizer was supposed to make them seem colder than after using the water. But in reality, both liquids were at room temperature.

Florez, who worked with kindergarten through 2nd graders, explains the concept behind the March 2nd hands-on activities.

Lina Florez shows children a digital thermometer reading during a Cena y Ciencias activity.

“So the kids were touching things, and they were feeling maybe one thing is hotter, or cooler. But we were trying to show them that overall, the temperature was the same. Our bodies can be deceiving, and so that’s why scientists develop instruments to specifically test everything, just so that we know that we’re a little faulty or misguided in how we perceive things. That’s why we develop tools to help us in the bigger picture.”

Florez believes the kids were receptive to the lessons, admitting that while it’s sometimes hard to get their attention, “When they sit down, they’re very receptive. They definitely want to play, and they definitely want to learn. It’s a great environment.”

Florez likes participating in outreach events like CyC because of the impact similar events had on her as a child. “I personally benefited from outreach, so I definitely want to help and make sure everybody has access to science and learning, and having the opportunities to explore what is out there: that’s what I do. I’ve benefited so I want to give back.”

Two youngsters listen while a lesson about heat and temperature is presented.

CyC planners also seek to provide something purchased or that kids can make during the lesson to take home to continue learning about the night’s topic. Addressing this idea of something youngsters can repeat at home was third-year Physics PhD student and CPLC BESO student Luis Miguel de Jesus Astacio.

“Usually we try to design the activity in a way that it can be easily transported to their house, so if they are still curious after Cena y Ciencias, they can just go through their house, play with stuff they find around their house, and they can just keep on learning. We try to use materials that can be found anywhere. It doesn’t have to be here or in a lab to be able to do these kind of things.”

Another theme taught earlier in the semester included: “Today’s Technology for Tomorrow’s Humankind.” The February 3rd activities were designed to give kids an appreciation of size scale, from atoms to galaxies, vacuum science, and materials for space travel, such as high pressure, temperature, etc. Later in the spring, CyC will address “Clean energy for all and everything” (May’s theme), which will deal with renewable energy, solar energy, batteries, etc.

Paul Ruess has fun with a youngster who's reading the temperature on a digital thermometer during a Cena y Ciencias activity.

However, while monthly lessons are related to science those who suggest the various topics are studying, carefully prepared according current pedagogy, and designed to engage various age groups, Menanteau says there’s an over-arching goal that’s even more important than communicating science content. “The principle of these sessions is not to create scientific literacy with the Latino kids,” but to “inspire potential scientists.” He explains that CyC’s main goal is Latino PhD, Master’s, even undergrad student volunteers serving as role models for Hispanic youngsters. Menanteau says CyC addresses a much-needed niche in the community.

“"I think this program helps repay the debt that the University of Illinois has with the community. We are one of the best universities in the world,” he continues, “and we interact very little..." We are one of the best universities in the world,” he continues, “and we interact very little with our communities, which suffer from poverty, immigrants, and the disadvantaged. Some of them rarely see themselves as potential scientists.”

So one goal of doing sessions in Spanish, according to Menanteau, is to inspire youngsters, many from Guatemala, Panama, or from Mexico, “who would otherwise never assume that they could be scientists. We don’t expect them to become scientists, but we want to give them the opportunity and role models, so that they can potentially see themselves, not just as landscapers or bus drivers. They can see themselves in the faces and skin tones of grad students or scientists who speak the same languages.”

Luis De Jesus discusses a thermometer reading with young children during Cena y Ciencias.

Agreeing with Menanteau about CYC’s providing Hispanic role models is Luis De Jesus. “I think it’s very important for the kids to get involved with science beyond classrooms. And specifically, in my case, I think it’s really important for the kids to see other Hispanics in scientific roles, so that they can project themselves in that context as well. I don’t think every single kid has to be a scientist in the future, but I think it’s very healthy for people to have a scientific intuition and just to be curious in general. I think activities like this one encourage both curiosity and help with scientific thinking.”

Regarding the impact of the March 2nd activities, De Jesus reports, “I think it helped them see the concept they might have been studying in their classrooms in a more practical setting.”

De Jesus, who got involved with CyC three years ago, has never met an outreach program he didn’t like. He’s involved in a number of others, such as CPLC’s BESO program: “I think events like these are very important. Right now, we are doing our best to expand and have many more schools [that] have similar programs. Last semester, we started a similar program at IPA (International Prep Academy). I think it’s important just to keep going, and see that there’s more to science than just learning and exams.”

Two Illinois students, Damián Castañeda and Deirdre Stone, show young visitors two bottles of liquid, rubbing alcohol and water, in preparation for a hands-on activity with them during Cena y Ciencias.

Like De Jesus, Joaquín Rodríguez-López is also committed to outreach. “I decided to become a professor because I love to teach and help others pursue questions about the world and how to better it through science. CyC allows me to do that with children that are starting to marvel and ask questions about the world.”

Rodriguez-Lopez also agrees with exposing young Hispanic children to the idea that there are scientists of color and that they, too, could become one. “ I think it’s important to be a role model, and to let children know that it is great to explore all these questions growing in their minds, and that if you pursue these, you may discover something new. Then, they realize they are scientists – in fact, when I am on stage with them, I call them “the scientists” – and that age, or skin color, or language has nothing to do with becoming accomplished scientists.”

He also believes another benefit of CyC is that students get to share the science they learned with parents and other family members.

Guadalupe Herrera (right) helps youngsters who are enjoying reading a thermometer during an activity.

“CyC is also about creating a supporting community around them, that helps them nurture their scientific interests,” he explains. “They see happy and accomplished graduate student volunteers, and professors, and university staff enjoying scientific activities. The pizza dinner is the catalyst to get them all engaged, but the real reward is getting the families involved and building the notion that exploring scientific curiosity is a great life choice.”

Cena y Ciencias Lesson Plans

Below are two 2019-2020 Cena y Ciencias sample lesson plans courtesy of Joaquín Rodríguez López:

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: Cena y Ciencias, I-MRSEC, K-6 Outreach, SACNAS, Underserved Minorities, 2020

For other I-STEM articles about Cena y Ciencias, see:

- Cena Y Ciencias Exposes Hispanic Elementary School Students to Materials Science at MRL

- Polímeros! Cena y Ciencias Program Teaches About Materials Through a Supper & Science Night

- Leal Science Night Exposes Local Youngsters to STEM, Role Models

- Cena Y Ciencias: Supper and Science…and Role Models, Courtesy of SACNAS

Children at the March 2nd Cena y Ciencias watch Felipe Menanteau perform a demonstration about heat and temperature.

Children at the March 2nd Cena y Ciencias watch Felipe Menanteau perform a demonstration about heat and temperature. An Illinois student, Edzna Garcia, has placed rubbing alcohol on the hands of young visitors during Cena y Ciencias.

An Illinois student, Edzna Garcia, has placed rubbing alcohol on the hands of young visitors during Cena y Ciencias.

.jpg)