OUR Seeks to Change the Perception of What Undergraduate Research at Illinois Looks Like

June 4, 2018

Karen Rodriguez'G, Interim Director and Associate Director of the university’s Office of Undergraduate Research.

Karen Rodriguez'G, Interim Director and Associate Director of the university’s Office of Undergraduate Research.

Exactly what is undergraduate research at Illinois? Is it one undergrad working in a lab? Is it a research-focused course with a capstone project? Is it not just a project, but a process? To all of the above, Karen Rodriguez’G, both the Interim and the Associate Director of the university’s Office of Undergraduate Research (OUR) says, “Yes!”

Rodriguez’G wears a couple of different hats at OUR. As Associate Director, she oversees the day-to-day function of the office. But as Interim Director, she describes her role as “forward facing for the campus—I am essentially the person in the office that faces everyone on campus.”

For example, she works with higher ups, such as the heads of the university’s eleven research institutes, to discover what undergrad research looks like for them, what sort of partnerships can be put in place, and how her office can help to provide opportunities for students. Plus, she serves on several committees that address these issues as well.

At the other end of the spectrum, she and her team work with students, encouraging them to get involved in research. Even incoming freshmen. For instance, she and the OUR team participate in units’ admitted-students days, where they talk to students and their families. “They’re very excited,” she acknowledges. “They want to participate right when they get here. And they can!”

According to Rodriguez’G, because of the size of the campus, one big plus is that there are lots of opportunities for research: “The thing is that this is a very big campus,” she admits. “There are eleven research institutes beyond the programs and departments and students' majors, which is great because it provides a lot of opportunity.” Many disciplines, including the sciences, such as chemistry, and engineering have really robust programs to support undergraduate research. “Research has always been a part of their education,” says Rodriguez’G.

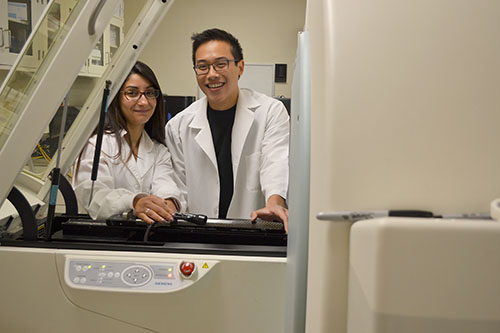

Engineering student Than Huynh (right) with his grad student mentor, Jamila Hedhli, conducting his undergraduate research in Bioengineering Professor Lawrence Dobrucki’s imaging lab.

Engineering student Than Huynh (right) with his grad student mentor, Jamila Hedhli, conducting his undergraduate research in Bioengineering Professor Lawrence Dobrucki’s imaging lab.

Conversely, the minus is, “That it's a very big campus!” she reiterates, which sometimes makes it difficult for students to get hooked up with the research experience that’s right for them.

So she and her team do what they can to help students figure it out. They do workshops, addressing everything from how students can get started, getting them to think about what their research questions are, and helping them to find faculty. “It's actually not that easy to find faculty on this campus,” she admits. “Some departments and programs are actually better set up for that. College of Engineering is great.”

OUR’s workshops help students get started by breaking the process down into manageable parts. The first step is for students to identify what their research interests are.

“You can't just assume, ‘I'm a bio student; I'm interested in biology,’ she says. “Well, what does that mean? Biology is a big field. Are there particular things you're interested in? You want to cure cancer? Work on mosquitoes? What is it you want to do?” So they help students come up with a small list of those.

Next they teach students how to search for faculty, both in and outside of their departments, in research institutes, or even in the research park, where OUR has connections.

Something else to consider is how students contact faculty—particularly those they don't have a class with. ”There is an art to contacting faculty via email,” she acknowledges, “being professional, laying out why students are interested. It shows they've actually taken the time to research what the faculty member actually does, instead of a generic email.” She adds that students also have to be persistent, show motivation, and exhibit commitment.

One of the keys for undergraduate students, especially those not in engineering or science, is learning how to write a research proposal—to “actually articulate what their questions are,” Rodriguez’G explains.

Then, once a student gets a research project, OUR also helps support it. The office has two research support grant cycles every year and also supports conference travel grants. And they’re always dreaming up ways to do more.

“We’re always trying to think about, ‘What’s the next step? What can we do? Part of this involves having conversations with stakeholders, whether it’s students, staff, faculty, even possible corporate partners.” One of the questions OUR staff ask constituents regarding undergraduate research is, “What can we do to not just support students, but actually push things forward?”

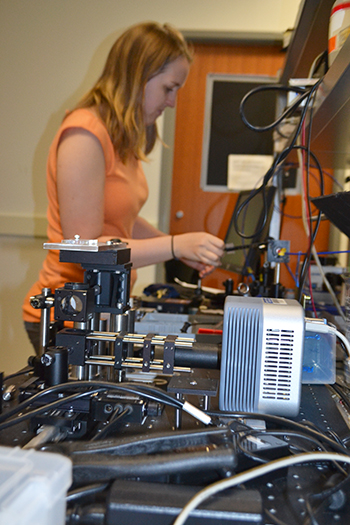

Undergraduate researcher, Elizabeth Woodburn working in the lab.

Undergraduate researcher, Elizabeth Woodburn working in the lab.

One way is to get more units involved. So every year, after the research cycles are over, she and her staff re-strategize based on what they’ve learned that year. They identify the gaps—units not involved in undergrad research—and brainstorm with their advisory board and faculty about how to address those. They’re also compiling a database of departments’ faculty liaisons in order to target those without representatives. For instance, they’ve identified one discipline—Business—for whom they don't see a lot of students, although that's starting to change. So one strategy might be site visits and talking to people. She also hopes to get someone from the College of Business on OUR’s advisory board.

Another strategy is to foster a campus-wide paradigm shift about what a research opportunity actually is. For instance, one stereotype she and her team fight is that it’s always only about one or two undergrads working with one faculty in a lab. So OUR is helping to create different kinds of research opportunities, such as one where students actually learn methodology and have a research project in, say, an introductory course.

OUR’s goal is building across the curriculum—striving for what's been called the connected curriculum. “That's really our goal,” Rodriguez’G admits. “That it's not invisible to students anymore. They can see a visible trajectory from introductory level course to their senior thesis or capstone project. Even between disciplines too.”

“Even in STEM,” she adds, “you're going to see pockets where it's not start to finish or made obvious.”

This is one area that interests Rodriguez’G—the program and curriculum development aspect of their duties. “I get excited when I see students are excited and faculty are excited about thinking and rethinking their curriculum and what that means, what can they do,” she says.

Also, to foster more research opportunities, OUR is attempting to get both grad students and faculty to think outside the box in terms of what undergraduate research is. So they’re trying to educate them to think about situations outside of the lab where they could use an undergraduate student. “I never thought of having an undergraduate student,” or “Oh, my gosh, when I was doing my dissertation research, I would have loved to have an undergraduate student,” are some of the responses they get.

Plus, Rodriguez’G emphasizes that, with the new design center going up, there's a real interest in fostering multidisciplinary projects and collaboration—design thinking.

She stresses that OUR’s role isn’t to provide research opportunities for students. “We don't provide any research opportunities ourselves,” she explains. “We just help students find them.” They also seek to “help programs and faculty provide opportunities so students have the ability to do research.”

Rodriguez’G and her team encourage units to make use of what is already on campus instead of reinventing the wheel—such as resources their office and others on campus provide. For example, while OUR wouldn’t be able to train an undergraduate student in a lab, one way they could encourage more faculty to apply for grants is to help take the burden off by providing components that would be important for an undergraduate student.

Karen Rodriguez'G, Interim Director of the Office of Undergraduate Research (center, foreground), listens as an Illinois undergrad presents her research durng the Undergraduate Research Symposium.

Karen Rodriguez'G, Interim Director of the Office of Undergraduate Research (center, foreground), listens as an Illinois undergrad presents her research durng the Undergraduate Research Symposium.

For OUR, key to serving as a resource is acknowledging what their office is good at. So they’ve learned to assess their strengths. “What does our office already do?” Rodriguez’G asks. “What do we have expertise in? Is it programs we already run?” “So what can we actually offer faculty who are applying for these grants so that they won’t have to do it themselves?” The idea is that her office would handle some of the more general things so faculty wouldn’t have to do them. She reports some of their strengths include substantial IRB expertise, plus training students in the ethics of research, as well as how a student navigates their mentor/mentee relationship.

So for some units, this is where a partnership with their office could come in handy. For instance, OUR could do workshops to help students to understand what an IRB is, what research ethics are, have students think about what it means to ask a research question and then follow that through. “This sort of idea,” she says, “kind of taking in a different way what we already do for our workshops. Since the office’s budget is small, she admits that they’ve “been more creative about encouraging partnerships with programs and institutes, so we're not the only ones that are paying for it.”

Another group they’ve been targeting is non-academic units. For example, they’ve had conversations with research institutes and NCSA, asking, “How can we help with our expertise so that your research scientists actually want undergraduates in the lab?”

One challenge they’ve encountered is that the structure of some institutes and labs is not already set up for an undergrad. For example, while some units might have the money to fund undergraduate research, they don't necessarily have the infrastructure for it. Since research scientists in some of the research institutes aren’t faculty, don't teach, and aren't part of the curriculum, course-based research projects might be a problem.

So the OUR team is constantly asking themselves, “What can we help do? How can we marshal our expertise to work with these?”

One strategy is encouraging mentoring through the U-RAP Apprenticeship program which OUR is partnering with the Graduate College to administrate. U-RAP matches undergrads with advanced graduate students, who will be the next generation of scientists. First, U-RAP provides training for grad student mentors via their “How-do-you-mentor-a-student?” workshop, which includes topics such as “How do you create a realistic timeline and a work flow?” and “How do you allow for the fact that you may actually have to train your student in what seems like fairly straightforward processes?”

For the U-RAP undergrads, OUR has taken material which used to be a workshop and created a class. “So we give them the big picture,” Rodriguez’G explains, so that they understand, ‘What is research in the larger sense, and across disciplines? What does it really mean?’”

“There are similarities across disciplines,” she continues. “Some things are a little bit more specific, but it is all essentially the same idea. You have to learn how to ask a research question. Once you have it, how do you go about answering it? What’s the methodology? What are the resources? What does it look like when you actually have your data? How do your organize it? Plus understanding the ethics of research.”

Another area they’re working on is something similar to U-RAP for the McNair Scholars, who already have their mentors.

Rodriguez’G reports that OUR, which was created five years ago, has grown a lot since she arrived in 2014, “Which shows to me the importance of undergrad research. There's a real push!” She also credits the more significant development grants they’ve been giving to faculty in the program, which they just started this year.

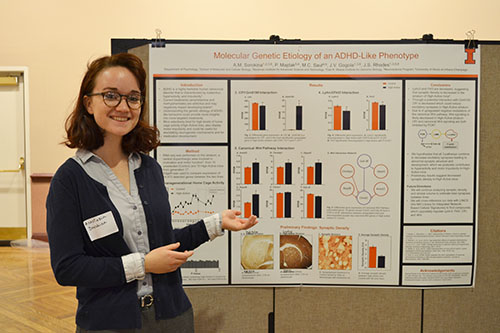

Anastasia Sorokina presents her research during the Undergraduate Research Symposium (image courtesy of Kristina Allen).

Anastasia Sorokina presents her research during the Undergraduate Research Symposium (image courtesy of Kristina Allen).

Of course, changing the face of undergraduate research on campus will also require additional funding. While in the past, most of the money given by corporate sponsors such as Monsanto, Technip FMC, the Stivic Foundation, and the News Gazette, has helped to sponsor the Undergraduate Research Symposium, their April event showcasing undergraduate research symposium. But according to Rodriguez’G, they’ve been thinking about soliciting funding not just for one event, but for undergrad research on campus as a whole. So over the last year, OUR has been creating “what we're calling, not necessarily best practices,” she clarifies, “but ‘What does an undergrad researcher look like? If we actually had to come up with an idea of undergrad research on this campus, what does it actually look like?’”

Part of this is a change in the perception of what undergraduate research opportunities look like, as well as a shift from just encouraging research to promoting the research process. “Because research process will include a research project, right? But it's a lot more inclusive, and it's actually bigger.” She hopes to promulgate creative thinking across campus about what students need to learn how to do, everything from asking questions, developing it to a research project, to the process of it itself. “For me, that's what's big,” she adds. “Thinking more creatively about what that means across campus.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Undergrad, Undergrad Research Symposia, 2018

For more I-STEM articles about Illinois undergraduate research, see:

.jpg)