nano@illinois RET Participant Tatiana Stine Hopes to Help Expose Youngsters to Nanotechnology

If you get them hooked early, the kids will think graphene is so cool, and that spark could make them the next big nano scientist.” – Tatiana Stine

September 6, 2016

.jpg)

nano@illinois RET teacher Tatiana Stine

A n instructional coach at a local school, Tatiana Stine is passionate about helping her teachers implement the Next Generation Science Standards—especially engineering. A participant in the nano@illinois RET program this past summer, she got to work with innovative nanotechnology while conducting research on graphene. And she not only learned a lot of new things, she developed teaching modules she plans to take back to her teachers. And one day, while waiting for gold nanoparticles to deposit on her device, she came up with a fun and novel way to teach youngsters about nanotechology—Gene the Graphene.

Stine, who has been teaching for 22 years, is currently an instructional coach for all grades and teachers at Robeson Elementary School in Champaign. When asked why she participated in the RET, she says, "My dream job in the future is to do science curriculum at a district level, primarily for elementary. Since nanoscience is becoming such a forefront in the academic and science world, you have to become familiar with it; you have to keep growing and learning…If my goal is to eventually be a curriculum director for an entire district, then I have to be constantly updating my content knowledge to keep up with the changing world of education.”

A step towards her dream job is getting to work on the Next Generation Science Standards for her district. “One of the goals for the Next Generation Science Standards is more engineering in the classroom,” Stine elaborates, suggesting that if teachers, “can be given practical ideas as of how to integrate engineering into the classroom, then it’d be done more often in elementary classrooms.”

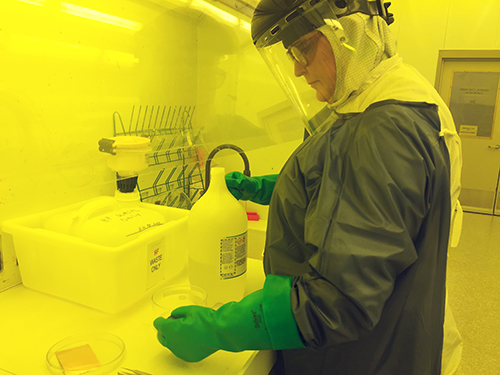

Stine at work in the clean room (photo courtesy of Tatiana Stine).

So her goal is to give teachers some practical lesson ideas. This is where her work in the RET program came in handy. By having the opportunity to complete research at Illinois, Stine was able to understand nanoscience better and, thus, be able to better translate this interesting, new science to teachers in her district. “So I’ve taken each step of my research process and made an elementary application for it," Stine explains. "So they could basically walk [students] through from synthesizing graphene to measuring data in a scaled-up version, with activities to represent every single step.”

Stine says the important thing is to get it down to the kids' level: “It’s taking a lot of these things and putting it at a 5 to 10-year-old level, and I think that’s the biggest thing that I’m going to take back are the ideas—the little tweaks—and you can take the world of nano into an elementary classroom. Obviously you can’t do the actual size, but you can scale it up and represent the same activities easily.”

One of Stine’s scaled-up activities was created to help explain the effects of strains on graphene circuits. In this activity, the students represent the graphene circuit: “They’re going to be passing balls in a circle, but then a strain happens, so you put an arm up because it’s deformed. Now what happens to your circuit?” While actively involving students, Stine’s activity helps to simplify a fairly complex concept to a level where young students can understand it.

.jpg)

Stine points to the image of Gene the Graphene on her poster at the end-of-the-summer poster session.

Working with graphene actually sparked another idea: “I was working on graphene," Stine explains, "We were sitting in a room one day waiting for our gold to deposit on our device, and I came up with Gene the Graphene …He’s going to talk about how he’s strong, and he’s flexible, no baths because he’s hydrophobic, all that, and he’s just wondering why nobody can see him, and so at the end of the story he gets discovered.”

Gene the Graphene.

Why Gene the Graphene? While piquing kids' interest in science, specifically nanotechnology, she hopes to inspire the next big scientist. “If you get them hooked early, the kids will think graphene is so cool, and that spark could make them the next big nano scientist.”

Gene isn’t alone in his journey, though. Stine depicts, “Gene’s friends in his classroom are like Bucky Ball and Flora Rine, and the teacher’s Mrs. Carbon-Nanotube, so they can all have their own stories eventually.”

Just like Gene, Stine wasn’t alone in this creation process. “A lot of people from the group I worked with want to expand and do more nano friends stories, so it could go places.”

Stine suited up to enter the clean room (photo courtesy of Tatiana Stine).

Stories on Gene and friends could be very helpful and educational to give students some background knowledge before learning about those scientific topics in class. Stine knows what it's like to not have the necessary important background knowledge; she experienced that coming into this RET. She reflects, “I was so overwhelmed at the beginning because of the content knowledge, I didn’t know anything about this when I walked in here.”

However, Stine admits that being overwhelmed was an epiphany regarding what students sometimes go through. The overwhelming and helpless feeling she experienced is something that some students encounter routinely; in fact, most can feel like this from time to time, especially with new, unusual material.

“The biggest lesson I learned is, you’ve got to remember that’s how those kids feel. The way I felt when I was being tossed all this stuff at me is how they feel. It was such a revelation to me, because a lot of times I felt afraid to ask for clarification, even though I didn’t understand what they were saying. Because I didn’t want to look dumb. And all of a sudden, bells are going off in my head, and I’m like, ‘That’s what’s going on with the kids!’ That was a huge take away.”

.jpg)

nano@illinois RET teacher Tatiana Stine presents her research on graphene at the end-of-the-summer poster session.

Stine stresses that it’s important for teachers to realize that all children are different: “You’ve got to go slow; you’ve got to take it into small pieces; don’t assume they all have this background knowledge. A lot of them won’t— specifically with science and specifically lower socioeconomic areas. I think that people assume that all their kids are coming in with the same background knowledge, and they’re not—just like people would assume that because we all have science strengths, we would’ve had this knowledge, and we didn’t. So it was a really good correlation for me to understand the frustration process with the kids as well.”

The nano@illinois RET is led and administrated by:

- PI Xiuling Li, Electrical and Computer Engineering

- Co-PI Lynford Goddard, Electrical and Computer Engineering

- Irfan Ahmad, Executive Director, Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology, and nano@illinois RET Program Manager

- Carrie Kouadio, Program Coordinator, Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology, and nano@illinois RET Program Coordinator

nano@illinois RET is managed by the University of Illinois Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology at the Micro and Nanotechnology Lab.

Story by Alexandra Anne Peltier, I-STEM undergraduate student, and Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photographs by Elizabeth Innes, except where indicated.

More: MNTL, Nano@illinois, RET, Summer Research, Teacher Professional Development, 2016

For additional istem articles on the Nano@illinois RET, please see:

- nano@illinois RET Teachers Discover Nanotechnology's Big Impact—Hope Their Students Will Too

- RET Teachers Experience Multidisciplinary Nanotechnology Research via nano@illinois

- 2015 nano@illinois RET Teachers Perform Nanotechnology Research, Make Modules

- Local Science Teachers Experience Research in NanoTechnology

- Local Biology Teacher to Introduce her Students to Research on Quantum Dots

.jpg)