Local Biology Teacher to Introduce her Students to Research on Quantum Dots

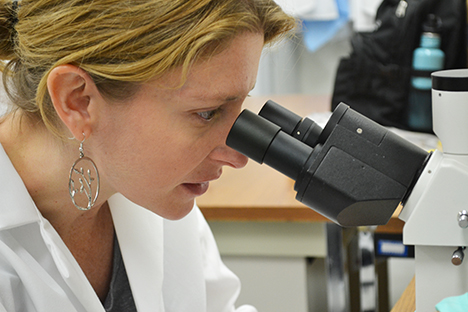

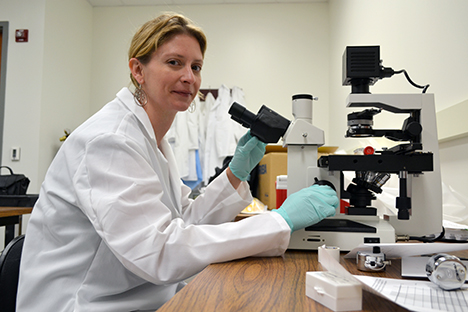

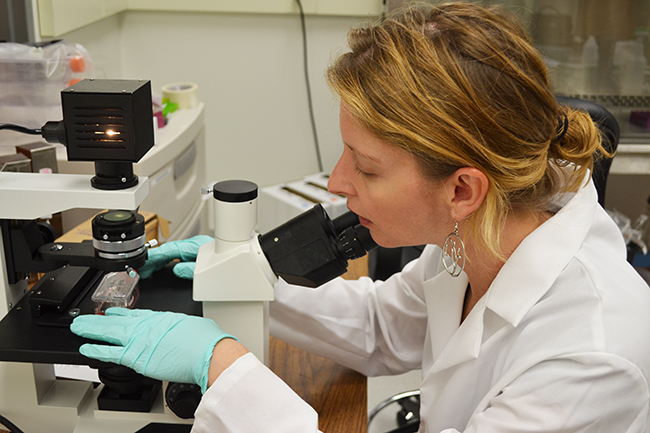

Biology teacher, Aubrey Wachtel, a Nano@Illinois Research Experience for Teachers participant.

July 10, 2014

“I teach in a very small school with limited resources," says science teacher Aubrey Wachtel, "so one of the best things that I can do is have experiences and then bring them back to the classroom." So this summer, Wachtel is experiencing nanotechnlogy while researching quantum dots.

Biology teacher Aubrey Wachtel from Villa Grove High School is participating in the NSF-funded Nano@illinois RET during the summer of 2014, where she is helping to conduct cutting-edge research in nanotechnology (quantum dots, to be exact), and hopes to adapt some of what she is experiencing for her students back at Villa Grove High.

No stranger to university professional development, Wachtel, who also teaches freshman physical science, participated in NanoCEMMS and really appreciated the hands-on projects she could use in her classroom: "I love watching the kids sort it out," says Wachtel. "It's really fun."

Why did Wachtel join this year's RET? For one, she's interested in the subject matter: "I think it's really cool that we're doing this HERE." And of course, there's the stipend. But also, after spending the first few summers of her teaching career vacationing, she finds she needs more:

"I need the change of pace to come back refreshed…Eventually I'm going to start seeking out some kind of experience. What better way to do it? Why am I not going to take advantage of an opportunity right here in my own town?"

What does she think of the RET so far? She calls it "an adventure."

Her research this summer involves methods for integrating quantum dots into human cells. (According to Wikipedia, "A quantum dot is a nanocrystal made of semiconductor materials small enough to exhibit quantum mechanical properties.") Once the dot is inside a cell, scientists can use its fluorescence to image the cell.

Wachtel is currently comparing quantum dots whose outside coating is likely to stick to what's inside the cell to dots whose coating is not likely to stick. She indicates that a couple of different ways to get them into the cell have already been established, "and we're just evaluating another method for getting them integrated into the cell without killing the cell."

In addition to unique research, she just plain likes learning. "I've been doing a variety of different trainings and lectures that don't really apply to my research, but are wonderful experiences, like I'm not going to get it anywhere else. I've really been enjoying that."

How helpful will her RET experience be in her teaching?

"I teach in a very small school with limited resources," she says, "so one of the best things that I can do is have experiences and then bring them back to the classroom. So I try to find things to do over the summer so I can bring back those experiences and share with the kids."

And the fact that she herself will have done what she expects her students to do will give her credibility with them. "But it's also a matter of being able to say to the kids, 'Well, when I was doing it…' It helps them to be able to internalize it, and it makes it real and kind of brings it down to earth for them. So that's really important to me."

However, unlike previous workshop experiences, when she took ready-made lesson plans/activities back to her classroom, one of the RET components is developing one herself, which she appreciates:

"I love that. I really enjoy curriculum development and coming up with ideas for activities…of exploring the possibilities: 'Ok, what can we do, and how are we going to make that happen?'"

A local science teacher, Aubrey Wachtel, performs research on quantum dots in an Illinois lab.

How is the module development going? Whachtel says she's still in the learning phase:

"I'm looking at materials and processes and procedures that I don't necessarily know how all of it works yet, so I'm having to do a lot of learning along the way."

For one thing, she needs materials appropriate for high school classrooms.

"First of all, is it safe to use these chemicals with these kids?" she asks. "Then, is it affordable? …Will it work? If I say, 'Let's use a chicken's egg as a model of a cell. What chemicals will pass through the membrane that surrounds the chicken's egg to make it so that we can do this? Or what chemicals will mimic the behavior of the quantum dots?' And we can still just use regular old cheek cells that you scrape and put on a slide. So those are all things I need to try out and see before I can develop an actual activity related to that."

One thing Wachtel's currently working on is osmotic gradients: "putting the cell into a concentration of the solution that causes the water direction to the cell and hopefully the particles will go into the cell."

This is something she'd like to take back to the classroom: "Ok, how can I develop a simulation of this, or a model of this that the kids can do that integrates some of the same principles of imaging?"

She believes her work in the RET will dovetail with her curriculum's section on cell osmosis and tonicity, which refers to the effect of a solution on a cell.

"So I'm looking at, 'Ok, well how do I integrate that into that part of my curriculum?' A lot of this will easily go into my biology curriculum about cells and how cells work."

What's another challenge? Being a student rather than a teacher: "It's been an adjustment to go, 'Ok, I'm going to sit and listen,' instead of being the one that's up there doing the talking," says Wachtel.

However, while Wachtel might believe the "teacher" in her is on hold for the summer while she is "student" and "researcher," this is not the case. As she rattles off 10-dollar words describing her research, the "teacher" in her comes out as she automatically defines terms, gives examples, and explains how she intends to adapt it for her students:

"In order for the outside of the quantum dots to be sticky, they're treated with a molecule that's amphiphilic: water-loving (hydrophilic) on one side and fat-loving (lipophilic) on the other side."

Wachtel goes on to explain that molecules in soap are amphiphilic, giving it the ability to "wrap around the grease on your hand and wash it away. So we talk about that in our lessons on the cells because the cell membrane is made up of amphiphilic molecules."

So with the program's six-week time-frame to learn the subject matter, conduct the research, then develop a module, what are the expectations in terms of research? Wachtel has discovered that research has its ups and downs:

"Part of what we're doing right now is developing an idea of what's a reasonable thing to expect to get done during this time. And that's hard to say, because things don't always go the way you want them to on the first try, so we're going to give it a shot, and in the meantime, I'm getting a better understanding of how this stuff works and what it is we're trying to do. And then develop a modular module that represents that work."

Always thinking of her students, Wachtel says this kind of trickle-down program is one of the best ways to expose them to cutting-edge research.

"I do think that this is the way to go when it comes to getting kids exposed to this kind of cutting edge content because you have to get that into the classroom and there are two options. Either you teach the teachers how to bring it into the classroom, or you gather up a group of people that take it to the classroom and do the activities and demonstrations with them."

Of the two methods, Wachtel says the teacher is more sustainable: "What I learn and bring to my classroom, if I integrate something in, I make it a part of my curriculum for years."

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Faculty Feature, MNTL, Nano@illinois RET, RET, Summer Research, Teacher Professional Development, 2014

For additional istem articles on the Nano@illinois RET, please see:

Wachtel places a slide containing Quantum Dots on a microsope in an MNTL lab (which this reporter later got to view).

.jpg)