I-MRSEC Workshop Seeks to Help Researchers Improve Their Public Engagement

The program addresses the needs of scientists who are motivated to engage but lack the resources to develop their skills and create plans for action.” – Gemima Philippe

Gemima Philippe, an AAAS Public Engagement Communication Associate from the Center for Public Engagement with Science and Technology, presenting the workshop via Zoom.

October 23, 2020

Intent on improving their scientific communication, particularly public engagement, 22 folks, mostly researchers from I-MRSEC (the Illinois Materials Research Science and Engineering Center) participated in the Center’s Science Communication and Public Engagement Fundamentals workshop on October 16, 2020. Presented by Gemima Philippe, a Public Engagement Communication Associate from the Center for Public Engagement with Science and Technology at the AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science), the online workshop addressed the importance of Science Communication, then tackled key areas participants should focus on in order to improve their own.

An interactive experience, the workshop, held via “Go to Meeting,” was comprised of brief lectures by Philippe, whose video was prominently displayed at the top, followed by opportunities for participants to use the “chat” component of the web platform (similar to a group text) to communicate with each other about themselves, their personal experiences, goals, etc. Periodically, Philippe even invited participants onto the “platform” to share—meaning the entire group could both see and hear them displayed next to Philippe. Otherwise, small videos of participants’ faces were ranged in rows below, similar to an audience.

Workshop content involved Philippe first delving into the value of public engagement about science, citing the importance of key elements she’d identified: identify your goal, define your audience, develop your message, determine your public engagement type, even evaluate then refine your message. After each topic, participants had the opportunity to contribute via chat. Plus, near the end, one participant even got to briefly practice their presentation then receive helpful critique. In addition, at the close, Philippe armed participants with tools and resources they could draw on to further improve their public engagement.

MatSE Associate Professor Andre Schleife. (Image courtesy of Andre Schleife.)

According to Philippe, her workshop gives scientists and engineers opportunities to “reflect on their public engagement interests and experience and think critically about what they want to accomplish and how to achieve it. The program addresses the needs of scientists who are motivated to engage but lack the resources to develop their skills and create plans for action.” Similar to that of I-MRSEC, her center’s vision is “for science and society to engage in conversations and learn from one another.”

One challenge Philippe believes most scientists face in communicating science is that they don’t necessarily “feel trained in a specific area before they are comfortable venturing out on their own. This can be a paralyzing obstacle,” she continues, “but we can help them overcome it. People communicate about things that are important to them every single day—and having conversations about science should be no different.” She says in addition to providing basic communications training, their workshops help to “demystify the process a bit and help scientists to recognize their innate ability to effectively share their research.”

Why did the workshop participants attend, and what did they hope to gain? Kathy Walsh, an MRL (Materials Research Lab) senior research scientist specializing in scanning probe microscopy and profilometry shares why she participated: “I'm looking to improve my fluency in talking about science at a range of accessible levels,” she explains. “Some of what I do is very easy to relate to. Other aspects of my work are harder to identify with since they deal with submicroscopic size scales beyond the realm of everyday experience.”

A faculty member, Andre Schleife, Associate Professor in Materials Science and Engineering (MatSE), attended the workshop to “build a framework for how to think about public engagement.” He reports “The workshop definitely accomplished that. I have a better idea now of what questions to ask and how to approach a new public engagement activity.”

Illinois grad student Kisung Kang. (Image courtesy of Kisung Kang.)

Also participating in the workshop was Kisung Kang, a grad student who works in Schleife’s lab researching the simulation of magnetic materials. Kang shares why he got involved: Before the pandemic, he had participated in various I-MRSEC outreach programs. Mostly involved K–12 students, he had visited Franklin STEAM Academy, a local middle school, to help with the lecture and hands-on activities in an outreach about batteries. He also participated in a virtual reality experience about materials visualization during a tour of MRL. “Whenever I met diverse people and students,” Kang admits, “I felt a small obstacle that might distract us from effective communication. I am curious about what causes this feeling, but I couldn't find the answer.” When he learned about the AAAS workshop, he signed up, hoping to “find the clue and improve my communication skill.”

Philippe maintains that one key to understanding how to communicate with non-scientists is to grasp their perception of who/what a scientist is. Consequently, after asking participants to briefly describe a scientist, they came up with this list. Responses ranged from a scientist’s exceptional characteristics (curious, examiner, expert, investigator, smart); their role (experiments, explore interesting problems, nature); and, of course, their stereotypical accoutrements (flask and goggles, lab coat, and specialized equipment. Thankfully, no one suggested the general public’s epitome of a scientist—an older white man with crazy hair…the Einstein-esque mad scientist.)

So, why does Philippe insist science communication is important? She contends that science and society converge on several issues, like healthcare, the economy, and climate change.

“Scientific evidence can inform these issues,” she maintains, “but evidence alone cannot answer value questions—the ‘whether’ or ‘why’ questions—related to these issues. Scientists need the tools to be able to effectively discuss these issues with other members of society.” She says that’s where their workshops come in.

Imparting why they feel science communication/public engagement is important, several workshop participants, including the I-MRSEC PI, Nadya Mason, shared slightly different views. For example, Mason says: "I think science communication and public engagement are integral parts of our jobs as scientists. For one, much of our research is federally funded—the I-MRSEC is supported by the National Science Foundation, for example—so the public and policy-makers should have a sense of where their tax dollars are going," she says.

According to Mason, that leads to an even more important point: "We need to better communicate our science so that the public and policy makers can make better choices – about whether to support the science, about the implications of the science, and even about the use of science and technology in their daily lives."

Adding that public engagement even goes beyond voters and policy makers, Mason mentions a key emphasis of I-MRSEC: "We also want to educate and inspire the next generation of scientists."

Andre Schleife (right) enjoys exposing a student to virtual reality during a visit to MRL. (Image courtesy of Andre Schleife.)

MRL scientists Kathy Walsh feels it allows non-scientists, even scientists in other disciplines, to keep on learning. Indicating that she does physics for her day job, but reads history for fun, she continues, “If it had been the other way around, I would have loved the opportunity to continue to engage with science as an adult. Not everyone who loves science does it as their day job, and not everyone who has a day job as a scientist does what I do. I love to learn new things, and I know others do, too.”

Underscoring what he perceives as a general a lack of communication or agreement between scientists and the public, Andre Schleife feels strongly about the need for better communication. In fact, that’s why he attended the workshop:

“I am very concerned about a seemingly growing disconnect of ‘the public’ and scientific results,” he reports, citing why he was motivated to become more active in public engagement. “I am also concerned about an apparent lack of understanding of ‘the scientific method’ in the general public and the increasingly common misconception that a personal opinion is of equal merit to a scientifically proven, evidence-based result that contradicts that opinion.”

(Inserting a caveat about his above statements, Schleife indicates that he’s not sure if this disconnect is actually happening and is based on actual data, or if this is just his impression. “But it seems to be what is happening a lot on social media these days,” he maintains.)

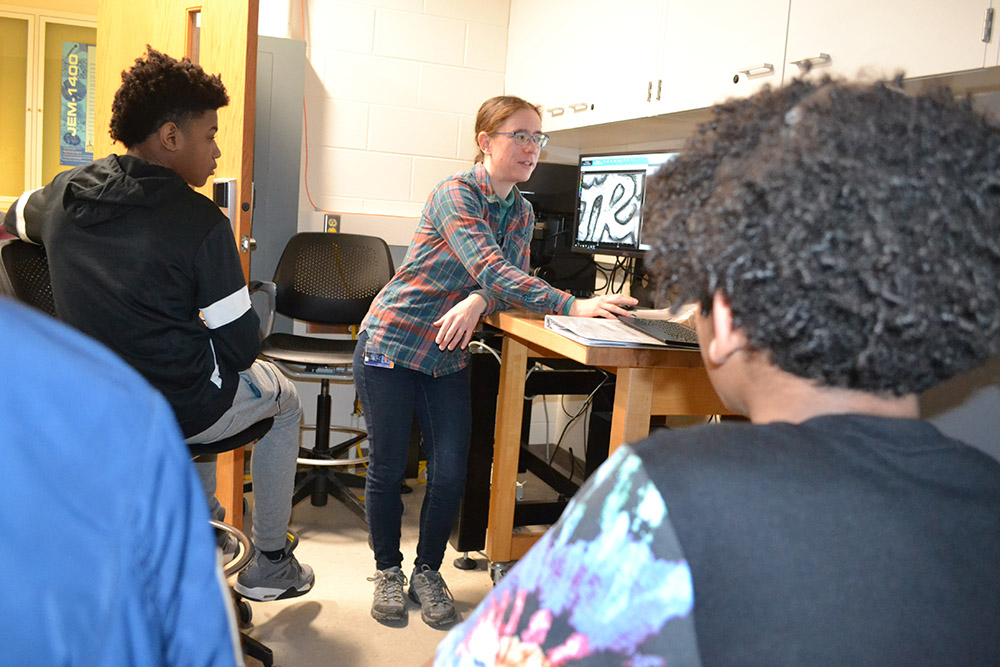

Kisung Kang interacts with a Franklin STEAM Studio student who's experienceing Virtual Reality during one of the school's field trips to MRL.

Continuing in this vein regarding the disconnect between scientists and the general public, Kisung Kang uses some creative metaphors comparing science to the air and science communication to the wind. “I think science is something like air,” Kang claims. “It is always around us,” but adds that sometimes, it’s not easy to prove its existence and understand its detailed information. “Scientific public engagement is the chance for people to face the science around them. Whenever people learn the importance of science, they become willing to support scientists and engineers.” Based on public support, Kang thinks scientists could feel more confident to continue their research and scientific discovery.

Continuing in a closely related analogy, Kang compares science communication to wind, indicating that the degree of science included might contribute to the disconnect. “As the wind might be a good way to feel the air, I think science communication works like the wind. If I deliver heavy scientific knowledge with professional terminologies, the public cannot enjoy the communication—like feeling strong wind or a hurricane.” He adds that this too strong delivery might even cause people to back away from science. He then compares somewhat superficial science communication to a paltry breeze which people can barely feel on a hot summer day, describing it as: “If I deliver too little scientific information, the students are barely inspired, and they don't realize the importance of science.”

Finally, he completes the analogy by describing a balanced presentation: “If I could deliver the appropriate science level with fun and important scientific messages, the students and people can enjoy the communication like the cool wind during hot summer. Therefore, effective communication is a key point for public engagement to draw and inspire the public and students.”

One key emphasis of the workshop was understanding one’s audience—figuring out their interests, level of understanding, attitudes, beliefs, etc. To help participants understand who their audience is, Philippe recommends that scientists do some research about them, then consider overlapping goals—interests they and those they'll be presenting to both have in common. She also encourages participants to consider what their audience will do with the info they receive. In fact, helping participants discern who their audience is so they can then adapt their public engagement accordingly is one of Philippe's favorite parts of her workshop.

“Personally, I love to really dig in to discussions about audiences during our workshops,” she states. “It’s important that scientists recognize the many facets of an audience’s identity and critically assess what they think they know about that audience.”

Adding that addressing community and representation are also important, she hopes one takeaway her participants internalize is this: “the importance of seeing their audience’s perspective when interacting with them.”

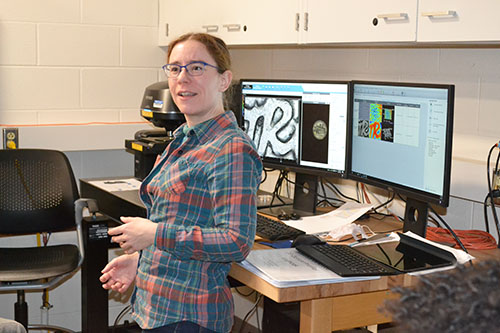

MRL Research Scientist Kathy Walsh interacts with Franklin students while demonstrating how a 3D Optical Profiler works.

Striving to understand and see from her audience’s perspective is Kathy Walsh, who describes her outreach as mainly tours and instrument demonstrations for groups and individuals, at levels ranging from schoolchildren through experienced professionals in different fields. She asserts that her target audience, in addition to kids who visit MRL on field trips, is comprised of parents, families, and chaperones, who share a common interest in helping their kids succeed.

“Some may not really be into science,” she admits. “Some have strong, hobby-level scientific interests themselves but have few opportunities to engage with labs in person, and some are scientists or engineers (so there are a wide range of backgrounds).”

Walsh’s goal for her public engagement is to connect scientific tools to common experience. “I've always loved science,” she says, “but almost went into non-science. I want to engage with people like me who took a different path. I hope they will see themselves as able to understand active scientific research (not to be put off by specialist terminology) and that they will feel welcome in labs. It would be nice to have more non-scientists (community collaborators) participating in research."

While Walsh mainly targets parents, one audience Schleife works with is high schoolers, such as periodically making presentations to summer camp participants who visit MatSE. Passionate about informing various audiences about the benefits of using computer simulations for materials research, Schleife’s research involves computational materials science/first principles simulations.

Kisung Kang teaches Franklin STEAM Studio students about Virtual Virtual Reality during one of the school's field trips to MRL.

Kisung Kang’s outreach efforts thus far have also involved programs for K–12 students, including serving as a guide during field trips, along with the public. Describing what he perceives as characteristics of a K–12 audience, Kang believes their interests originate from a “natural curiosity about the world,” but acknowledges that they might have difficulty “understanding difficult knowledge.” He also suspects they might need help in grasping “simple and straightforward scientific logic.”

Kang’s public engagement goals involve the interface between the public and scientists. “I hope the scientific interest of the public is promoted by this interface,” he says, adding that ‘Especially for K–12 students, I want to give positive insights to scientific careers as one of the choices.’”

What did participants glean from the workshop? One takeaway Schleife hopes to implement is the structured approach Philippe shared about how to plan, implement, then characterize a public engagement opportunity. “That was very helpful,” he admits, “and gives me a way to think about how I can approach this.”

Re Walsh’s favorite part of the workshop, she acknowledges that she benefitted from talking shop with two professors who do outreach activities with different scope from one another. “It's nice to see that even highly experienced science communicators still critically analyze their style, learn from each other, and try new strategies,” she says. “For me, the most helpful advice was Nadya Mason's comment in a break-out session about how many themes or points one can practically expect to communicate effectively in a given amount of time.”

Kang’s favorite part of the workshop was the message refinement. Upon learning that one’s message should be memorable and meaningful, he did an exercise in the breakout room. Having set his audience as K–12 students, he reports, “My original goal was to let the students learn that ‘Supercomputer calculations can be used for the research of antiferromagnetic materials.’” However, he realized that his message included professional terminology he would need to explain—antiferromagnetic materials. After discovering that the info he had originally wanted to deliver was “Simulation can be used for the research,” he reports: “I truncated some information and made it more straightforward. Finally, my goal became to let the students learn that ‘Simulation can be a part of materials researches.’”

Gemima Philippe. (Image courtesy of Gemima Philippe.)

Equally rewarding for Kang was contributing to the message of a colleague who wanted to share about her virus study and DNA analysis, but was finding it difficult to explain to the public about DNA, which delivers specific information about individuals. “I suggested using the barcode as an analogy,” he reports, “since people commonly know how the barcode works.” To his delight, his colleague liked his suggestion and planned to use it in the future.

What Philippe finds most rewarding about teaching science communication workshops is the lightbulb moments. Although as a facilitator, she leads discussions about the same communication and engagement practices during each workshop, she never tires of it. “The amazing scientists we work with make each workshop unique,” she claims. “I really enjoy those moments when a participant internalizes one of our concepts and a noticeable shift begins in how they talk about engagement.” Indicating that this lightbulb moment might happen at various points throughout each workshop, she calls it “super rewarding to witness.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

For more I-STEM articles about I-MRSEC fostering science communication, see:

- I-MRSEC’s Virtual Coffee & Cookies Hour Encourages Collegial Communication Among Researchers; Bake-Your-Research Contest Fosters Fun!

- Principiae’s Jean-luc Doumont Teaches I-MRSEC Researchers How to Deliver Remote Presentations…Remotely

- I-MRSEC’s Principiae Workshop Targets Improving Researchers’ Presentation Skills

- How Tweet It Is! I-MRSEC Workshop Helps Scientists Incorporate Twitter into Their Scientific Communication Repertoire

- I-MRSEC’s Alda Scientific Communication Workshop Trains Scientists to Relate to Their Audience

Kathy Walsh teaches Franklin STEAM Academy middle schoolers about scanning probe microscopy during a Franklin tour of MRL.

.jpg)