CS Professor Geoffrey Challen Embraces Teaching—Introducing Students to Computer Programming and the CS Community

“Programming is the most powerful skill on Earth. If you want a general purpose problem-solving skill, programming is it. Computers are by far the most powerful problem-solving tool we’ve ever built, and until you learn how to program, you can’t really fully use them. If you really want to unlock their full potential, learn programming.” – Geoffrey Challen

Geoffrey Challen working at his computer in his Siebold office.

March 14, 2019

Geoffrey Challen recently heard a quote that got his attention: “Two codes that students need to learn: one of them is the constitution; the other is how to program.” While he didn’t comment on the first code, it’s pretty clear that he wholeheartedly agrees with the second. However, as passionate as he is about programming, there’s one thing the Teaching Associate Professor in Computer Science (CS) at Illinois is even more passionate about…teaching students how to program.

While originally focusing on research earlier in his career, Challen reports that, “Along the way I was really sort of discovering that I really like teaching,” telling himself, “This is really meaningful to me; and this is kind of what I want to do.” So now, he’s mostly using his research and programming skills in support of his teaching.

How'd he end up at Illinois? Although he’d applied to several different CS departments, he says, “This is the department that really stood out to me.” Several things about CS at Illinois appealed to him “Computer science is really well established here on campus,” he reports, and, “The progress they’re making in gender diversity was really important to me.” Another aspect that intrigued him was the department’s CS+X program, which he calls, “pretty cool.” (In case you aren’t familiar with CS+X, it’s a degree option that allows students to pursue a flexible program of study incorporating computer science with technical/professional training in the arts or sciences, such as CS + Chemistry or CS + Advertising.) So he picked Illinois.

Two CAs help a CS125 student (left).

When Challen arrived in Fall 2017, he took on the challenge of teaching CS125: Introduction to Computer Science. Challen has wanted to teach an intro-to-CS course for a long time. For one, he feels they're “ground zero for a lot of the problems that we have in this field.” He shares his course goals.

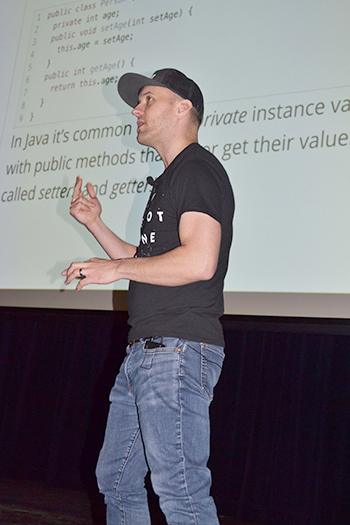

“Intro is where things start, right? And I think that in our intro courses, we kind of have a responsibility to make sure that, first of all, we give students a feeling for what the major is like, but also that we provide them with a good foundation for success later. We need to make sure that they understand what it takes to succeed in the field.” In addition to helping students learn enough so that they go on to succeed, he hopes to give them a sense of what it’s like to be computer scientists.

CS125 is for CS majors, plus students who have a serious interest in coding. What’s interesting is that the vast majority of students taking the class are not actually CS majors. For instance, of 600 students taking the course this semester, only 10 are CS majors. Why so many non-CS students in his course? “I think there’s a huge amount of interest in computing, right, even outside of our major,” he says.

Geoffrey Challen interacts with a student.

For example, of 1500 students who’ve taken CS125 over the last two semesters, only 20% are CS or CS+ majors. Of the rest, some are undeclared or from PREP, the Division of General Studies’ Pre-Engineering Program which allows highly qualified students not currently in Engineering to prepare themselves for possible transfer into the College. Plus, a lot of students want to transfer in to major or minor in CS. Others want to learn to code because it will be useful in their field down the road. However, according Challen, it’s not only difficult to transfer into CS; registering for CS courses is tough because the department is at capacity. So he advocates using fewer professors to teach more students.

For instance, in 2017–2018, around 1300 students enrolled in CS125 which was taught by three instructors in multiple lectures; two in the fall and one in the spring. However, when Challen took over the class, his goal was to not lecture more than once a day. (“Once is enough!” he admits.) To accomplish this, the class moved to Foellinger in Fall 2018, which allowed them to not only have just one lecture, but also to grow the size of the class. So in 2018–2019, 1500 students enrolled in CS125 all total with just two instructional units: Challen, who taught the class by himself, both last fall and again this spring.

The idea he’s implementing in the course is called Teaching at Scale, which he defines as: “Bigger classes, fewer resources.” So his goal is to educate large numbers of students and give them a common experience, using technology to make it more efficient. “Whatever we can do to do higher quality instruction through technology, I think, are things that are going to benefit students.”

Geoffrey Challen at his computer in his Siebold office.

Challen also advocates for Teaching at Scale in order to make college more inexpensive. He has serious concerns about affordability, indicating that college should provide a way for people to rise up in the class hierarchy in our country, especially students from a lower socio-economic status, often underserved minoritiesl.

“There’s supposed to be a way for people to enter the middle class, right? Work hard, get an education, you get out, you get a good job, and now, if you’re smart, and if you picked up things along the way, you may be able to provide a better life for your family. Once college stops being affordable, then that pipeline starts to shut down.”

In fact, the Teaching at Scale notion was another thing that drew him to Illinois. “I really think that we have to learn how to teach at scale, and how to improve instructional efficiency,” he claims. “This is something that our department thinks about.” For example, when CS interviews teaching faculty candidates, they’re asked to talk about effective teaching at scale.“ This is something that matters to us,” he continues.

Two students enjoy CS125.

When Challen says, “bigger classes, fewer resources,” he’s really talking about fewer financial resources, like instructors, because his goal is actually to provide his students with tons of resources: “Because we actually have a lot of resources available to our students,” he clarifies, “but they’re resources that don’t cost money every semester, right?” he explains. For example, Challen and his team have developed a number of electronic resources for the class. And while it did take a lot of man-hours to develop the materials, they can be reused over and over, semester after semester.

“We put together a lot of great systems that back up the class,” he admits. “There’s probably tens of thousands of lines of code now that are involved in running CS125 and providing that experience for the students. Again, those consume time to create, but now they just work.”

For instance, one thing Challen really cares about is enabling students to know how they’re doing in class. So he and his TAs built this grading site where students can see their progress immediately: “I want students to see, to be able to always know exactly where they are on the histogram…It shows them where they are relative to their peers. And then it also allows them to figure out, y’know, any mistakes they might have made.”

Two CAs (right) help a student in CS125.

These systems he’s developed are not just beneficial for the undergrads; they also help him and his TAs with grading by tracking lecture participation, homework, and exam grades. In fact, a student doesn’t just get credit for showing up and being a warm body during the lecture; he or she must open up the slides and follow along, because Challen’s program logs every time a student switches (or doesn’t switch) to the next slide.

“What we’re trying to do in CS125 is pretty innovative,” Challen claims. “Use code during class (in a browser!)”

His system also comes in handy when he or one of his TAs need to explain to students why they didn’t get credit. Instead of receiving a relative judgment call, his students can see why with their own eyes. “So when a student asks, ‘Oh, why didn’t I get credit?’ I’ll just send them to this page, and I’ll say ‘Well, you know, in this case, you missed a bunch of slide transitions, so you didn’t get credit for that,’” he explains.

He also designed a course forum which allows students to ask questions regarding concepts they might be confused about. “So we have a really nicely done course forum that I set up for students to use,” he explains. “People are asking questions on here all the time.”

Geoffrey Challen helps a CS125 student.

While many of Challen’s resources are electronic, he’s also got quite a few of the good old-fashioned kind—people. With 600 students in CS125, Challen obviously needs some help to keep the course running smoothly. He calls “this incredible group of people associated with the class” one of his favorite things about the course. Not only does he have nine grad students who serve as TAs; he has 150 CAs (Course Assistants), undergrads who are helping out with the class. “We couldn’t teach the class this way without the CAs,” says Challen. “This is the kind of resource that an online class can’t provide.”

In keeping with his Teaching-at-Scale mandate, CAs don’t get paid; they receive one hour of CS course credit. “They are doing this as part of a learning experience where they are learning how to help other people,” he explains.

He meets with his CAs, mostly freshmen and sophomores, once a week or so to train them to hold office hours which are officially Mondays and Wednesdays. But basically “Any day of the week, a student can come in and receive help in their own room,” he reports, referring to the CS125 room in the basement of the Siebel Center. Challen says he appealed to the CS community regarding his need for CAs and received a fantastic response.

Challen watches two students work. In the top right is the celebratory "Victory" sign.

About 20% of the CAs are actually students who took CS125 last semester and who are willing to come back and help out. Should be a piece of cake, right, since they’ve taken the course already? Nope. Challen says it’s quite challenging. “Trying to help somebody else with their code is incredibly hard,” he acknowledges. “It really pushes—Y’know, some of these students are superstars, right? Some of them were incredibly good when they took the class. But you put them next to a student who is struggling with a problem, particularly if the person has decided to approach the problem a slightly different way, and it’s hard! It’s hard.”

The level of difficulty they face is just one reason Challen is so amazed by his CAs. Calling them “fantastic,” he’s particularly impressed by how patient they are with the students. In fact, he brags that he has a handful every semester whom he classifies as “angels.” “They are so patient; they are so nice; they’re so supportive, y’know? They are constantly encouraging students. Students will ask and say, ‘Oh, this may be a dumb question,’ but the CA will say ‘No, there’s no such thing as a dumb question; you’re still learning.’ I always love that.”

A CS125 student listening to Challen's lecture.

In addition to the cadre of CS-savvy class assistants, Challen felt it was important for his students to have their own space. “Students in my class know that there’s a room in the basement of Siebel that they can go whenever they have a question, whenever they need help, whenever they’re struggling. Whenever they want to do some work on the class, they can come in and sit down. They have other people around them that are in the class that are helping them out. They’ve got CAs there to provide encouragement and guidance.”

Plus, as an incentive, sometime Challen sends some Insomnia cookies down to the room“for fun.” Or the students can turn on the stereo system. Plus, Challen (who has an electric sign fetish) has installed a “Victory!” sign which lights up briefly to celebrate when students successfully complete an MP (machine problem)— these are projects thatmake up a large part of the course.

“For me,” Challen adds, “this is also a part of ushering them into what I consider to be the community of people who are involved in computer science and how we work together…how generous people are with their time.”

Challen goes on to share that having CAs works because of the sense of community in CS. “Computer science as a field has an unusual community component to it,” he explains, citing that across CS there’s a generosity and willingness to help each other. “You go online and you find all these great resources. You go online and you find all these people sharing code with each other…One of the things I’ve always liked about computer science is it has a real communal feel to it.”

And it’s not just his CS125 students who are learning about community, but the CAs as well. Challen says he always tells them, “‘This semester it’s you answering the questions sometimes, but next semester, or a couple semesters from now, you may be in a class, and some of these same students may be helping you.’ That’s how it works in tech. Some people know some things, and they don’t know other things. Sometimes I ask people for help, sometimes people ask me for help.”

CS125 students listen during a CS125 lecture.

While Challen might have chosen teaching over research, he’s still a researcher at heart when it comes to improving his course and the instruction. For example, he’s started a multi-semester project gathering as much data as possible about the class, which involves building a lot of their own tools. In Fall 2018, they launched the IntelliJ Plugin, which tells them how long students are spending on assignments. He’d like to get to the point where he records every student interaction with the class and the material. “So any time a student is working on one of our assignments, what did they submit, and what was wrong with it? Any time they look at a slide.” He adds that they already have a data set about slides from last semester of “like 10 million slide views that we are starting to look at to kind of understand how students view the slides.”

Another tool they’ve designed is an app that will record when students go to office hours. Students will install it on their phone, and when they come to office hours, a Bluetooth proximity beacon will record whether or not the student’s phone is in range of that device.

It won’t be Big Brother in Orwell’s 1984; Challen insists that they won’t know where students are the rest of the time, and won’t track their location all over campus; all they’ll know is when they’re in office hours. Their goal is to “not only understand how that relates to students’ success,” but they want to understand how to “be able to do things better,” by answering questions like, ‘When should we hold office hours?’ and ‘How many CA’s should we assign?’ and ‘Which CA’s are effective and which CA’s are not?’” Challen claims that once they’re done, it will be the most detailed data set about a class at Illinois.

Geoffrey Challen lecturing to the class.

Down the road, they also hope to get precise data regarding exactly how much time students spend working on MPs. They’re also seeking to know whether they’re focusing too much on assessments and to figure out what they might be able to do differently. (While he deems tests to be important, he sees them as a necessary evil: “Testing environment is a scary place!” he claims, regarding not focusing on assessments too much). Luckily, they don’t have to build a system to access those data. Prairie Learn tracks how much time people have taken on a particular assessment.

However, were they to rely on course technologies, such as Moodle, to supply the data they need, they’d be missing many important pieces. That’s why they’ve had to build so many custom tools. So far, his team knows when students work on homework, every time students submit it, what was submitted, and what was wrong with it. They know when students work on assignments and how long they spend on them. Challen and company also built a special plug-in that integrates into Visual Studio to tell them when students start working and when they run test cases.

Why is it so important to know how much time students are spending on course components? For one, Challen wants to make sure they’re doing the work.

“I really firmly believe, and I tell the students this all the time, programming is a skill, and you get better at it through practice. And if you do the work, it will pay off.”

He also wants to help students succeed in the class by ensuring that they’re engaging in the kind of behaviors they need in order to succeed, such as spending the time on the quizzes; starting the MP’s early enough so that they can finish; coming to office hours when they need help; going on the course forum when they have a question. “We can do a huge amount more in helping students learn how to succeed by the behaviors that are associated with that,” he claims. “It’s the same thing with our forum. There are some students that never use this, and some who use it all the time.”

Another reason to track time spent is to gauge CS125’s level of difficulty. He admits that this is one of the things he and his team think about a lot. “I wanna make this course as hard as I can without it being too hard,” he confesses. “And where is that line? Part of that is figuring out how much time students are spending on things.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Computer Science, Undergrad, 2019

.jpg)