Cena Y Ciencias: Supper and Science…and Role Models, Courtesy of SACNAS

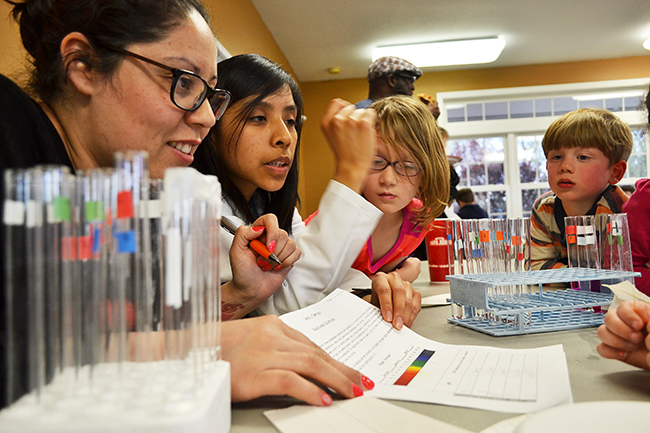

During Cena y Ciencias, Madeline Lopez, a PhD student in Microbiology and member of SACNAS, works with a student during a hands-on activity about acids and bases.

May 18, 2015

The program, called Cena y Ciencias (it’s Spanish for Supper and Science), meets on Monday nights once a month. For dinner, there is pizza. The science is presented by Illinois grad students (and undergrads) who are all SACNAS members. This particular Monday night in April, the science involved a hands-on activity about acid-base reactions. Wearing the conventional garb of scientists—white lab coats—the students shared their passion for science with the excited young students who were clustered around them, eagerly learning about acids and bases while glibly chattering in Spanish.

Sponsored by NSF funding awarded to faculty in Chemistry, Microbiology, and the PEEC program at the University of Illinois, Cena y Ciencias is unique among the many outreach events held in our community. What sets it apart? It's done solely in Spanish. And what was even more amazing to this reporter when she visited: the Hispanic kids weren’t the only ones fluently speaking Spanish; African-American and White kids were too.

Left to right: SACNAS members Kimberly Sam, an undergraduate in MCB, María Bautista (in the back), a PhD student in Microbiology, and Ariana Bravo (center), work with Cena y Ciencias participants during a hands-on activity about acids and bases.

Even Ariana Bravo, President and an Outreach Coordinator for the Illinois student chapter of SACNAS (the Society for Advancement of Hispanics/ Chicanos and Native Americans in Science) admits, “The first time we did this, we were so surprised to see all these White Americans and Black students all speaking Spanish fluently, even though they are first graders, second graders.” She confesses that when debating whether SACNAS should be involved in the project, she and other members told themselves, “‘It’s not going to work!’…We thought we were going to have a language barrier. But, no, it’s not an issue.”

It’s not an issue because the students who participate are part of the Dual-Language Program at Prairie and Leal Elementary Schools. Dr. Amanda Harris, the program’s Family Coordinator at Leall, explains what makes her program unique:

Dr. Amanda Harris, Family Coordinator of the Dual-Language Program at Leal School in Urbana.

“It’s geared towards both groups to be bilinguals. Whereas in previous models of Spanish language and ESL services, the goal was for the Spanish-speakers to speak English; in dual-language, the goal is for all students to be bilingual.” And if Cena y Ciencias is any indication, it appears that they are.

According to Harris, the school makes Spanish the source of knowledge in the classroom in the early years, but by the time they get to fourth and fifth grades, “It’s 50-50,” (half English, half Spanish). And the youngsters, who have been in the program since Kindergarten, are bilingual, which makes a program like Cena y Ciencias possible.

What also makes the program possible is the presence of the SACNAS folk. According to Brenda Andrade, a Chemistry Ph.D. student and Vice-President of SACNAS, their mission is “to diversify the sciences and to make science accessible to everybody.” They particularly want to make science accessible to Hispanic youngsters and are thrilled when given the opportunity to participate in dual-language activities like Cena y Ciencias, which allow them to serve as role models to these youngsters. “So they see that we speak Spanish; we are from Hispanic countries, and we want to share that with them, and that it’s attainable for them too.”

To further reinforce the idea that people of color can be scientists, all Cena y Ciencias role models must look the part. According to Harris, they all wear the traditional attire of scientists—white lab coats—because “We wanted to open up the visual image that the word scientist connotes for kids,” explains Harris. “By putting the authority of science and professionalism and also putting the image of scientists of color…it opens up the possibility for these kids to imagine themselves as scientists, to imagine themselves going to college and to grad school.”

Brenda Andrade (left) and another SACNAS member, Sandy Perez, an undeclared undergraduate, teach Leal students about acids and bases during Cena y Ciencias.

Harris indicates that Cena and Ciencias hopes to challenge the idea of the White-male scientist/doctor. “It shows them that scientist also means woman of color; it means Spanish-speaking man…so it really widens the students’ concept of what the social possibilities are, of what one’s individual possibilities are, and also that authority can come from many places that previously in society it did not come from.”

Andrade knows personally the impact outreach programs can have on a young person’s notion of who they can become. Andrade, who hails from L.A., reports that in high school, she and some fellow students visited a nearby university’s chemistry department on Saturdays and did experiments. This program instilled in her a love of chemistry and set her on her current career trajectory: to be a Chemistry professor and teach undergrads. “So I think that kind of opened up that possibility,” admits Andrade, “that ‘Oh, I can do this. This is easy!’”

Left to right: Alexander Palmer, a PhD student in Microbiology, and Ariana Bravo demonstrate to students how the color of the solution changes during and acid/base reaction.

Unlike Andrade, Bravo didn’t attend any outreach programs as a child growing up in Puerto Rico. She got engaged with science later on, in high school, when she became “fascinated with how complex biology systems were, and all of the things that I could understand if I knew more biology.”

However, Bravo knows all about role models; it was the influence of one in her own life that started her on her journey. Her best friend’s mom, a scientist working to develop a vaccine for HIV, motivated Bravo to choose a career where she could make a difference. “So it means that I could have such an impact if I have a career in biology,” she had told herself.

So, like her own role model, Bravo, a Ph.D. student in Microbiology, is also currently researching viruses in hopes of curing disease. “If we understand how viruses evade the immune response, then we are in a better position to develop antivirals and therapeutics and vaccines, and also learn more about the immune system and what kind of diseases there are.”

SACNAS member Elena Montoto, a PhD Student in Chemistry (center), demonstrates to participants how the color of the solution changes during and acid/base reaction.

And like the impact her own role model had on her, she hopes to have a similar impact on some other young person’s life:

“That’s when I decided to inspire someone else. So even though I didn’t participate in a program like Cena y Ciencias, I would have loved to—just have someone as a role model. That’s why all of our volunteers, that’s their goal: to be role models for these students. To have them say, ‘I could be like you.’"

Now, as a part of SANCAS, both Bravo and Andrade are heavily involved in outreach. And they acknowledge that part of their motivation is to get kids hooked on science and possibly even recruit them into their own fields. “Yea, yea, yea. Definitely,” admits Andrade. She says programs like this are “huge” in helping SACNAS members fulfill their mission, which is to diversify science.

“So these children are being exposed to science for whatever reason. Because if they don’t have examples in their family, or they don’t see the sciences as a career choice, then we expose them to the sciences, and give it a fun component, they’ll be more likely to choose science as a career path.”

Falling short of getting them to choose science, she hopes to at least get them to consider “just that college is accessible, and that they can do it too, no matter what their background is.”

Ariana Bravo at work in her lab researching viruses.

Like Andrade, Ariana Bravo also hopes to convince these youngsters (and their parents too) that college is in their future—just like it was for her:

“I think, for me, I’ve never had a doubt. It was like: high school…college.” That’s what my mom told me all the time. She encouraged me: ‘You can do whatever you want. No matter where you’re coming from, no matter your economic situation, you can go to college and beyond.’ And that’s what we want to tell these parents and the kids as well.”

And the parents appear to be getting the message. Bravo reports, “I have had parents that come to me or to the other volunteers and say, ‘I want my kid to be like you, to go to college like you. And it’s just so rewarding when they say, ‘Tell me what you did to be where you are right now!’”

She indicates that she and her SACNAS cohorts also try to give parents tips, like, “Our parents encouraged us when we were growing up,” then she rattles off her mom’s advice, like it was yesterday: “If you want to be something, whatever it is, be the best at it. Be good at school from the beginning, and that will open all doors, and you can go to college and be a scientist.” Or— like Bravo—a Ph.D. student at the University of Illinois researching how viruses evade the immune response.

Bravo also sees the outreach as an opportunity to educate the public: “We as scientists really lack the ability to communicate with our community, and that’s why the community is so afraid of science, afraid of vaccines, afraid of new discoveries, because we don’t communicate what we know, and they don’t understand what we do, and they think we’re doing horrible things in the laboratory, which is not true. As important as it is to have new discoveries in the lab, it’s important to tell the community just what we’re doing, and, 'This is why it’s great for you,' one-on-one, so they’re not afraid of us or of science in general.”

In addition to Cena y Ciencias, SACNAS members do a lot of other outreach events. Andrade reports that they don’t have to advertise either. In high demand, the group has carved out a niche for itself in terms of outreach to underserved population groups and is contacted frequently: “I think they see us as a way to get bilingual people involved,” she admits. And the group is delighted to help out: “Any opportunity that we get to do outreach, we do, even at the high school level.”

Two young Cena y Ciencias participants get a close-up look at an acid/base reaction.

For example, at a recent Latino youth conference, they not only did a chemistry demonstration (“Those are the exciting demos,” Andrade confesses. “We can make stuff blow up!”), but a workshop on applying to STEM majors in college. They educated participants on why STEM is important, what majors are considered STEM, and STEM career opportunities (not just chemistry, but also engineering, math, technology, etc.).

Beyond providing local outreach to K-12 students, the Illinois chapter of SACNAS also fosters peer mentoring among the local membership here on campus which, while comprised mostly of graduate students, includes undergrads too. Additionally, it is part of a national society whose mission is to advance Hispanics/Chicanos and Native Americans in science through a number of strategies, including access to a network that includes science professionals who are part of professional chapters of SACNAS. Students from the local chapter get to network with those mentors through the annual national conference. In fact, several local SACNAS members recently met a professional who works for MONSANTO, who invited them to visit the St. Louis plant, where they spoke with Latinos in the company and learned of job opportunities. “There was a real connection made,” says Andrade.

Left: A Cena y Ciencias participant enjoying the activity.

What kind of impact has Cena y Ciencias had?

“They learn!” exults Andrade. “They do. Like when they raise their hands, and they can remember things, they get super excited! And they take it seriously. They want the challenge. So that’s the one thing I see in them: they’re learning, and they’re challenged, and they’re engaged. You can tell. ‘Oh, I want to mix it!’ Even if they’re really shy. I had a little girl at my table who was really shy. But I was like, ‘Do you still want to mix the solutions?’ And she’d be like, ‘Yea, Yea.’ But you have to get them out of their comfort zone. They’ll still participate, and they’re engaged.”

According to Harris, Cena Y Ciencias gives young participants a sense of ownership. “If you think of it in the context of a society where all things are not equal, and we are vested in serving a social-justice education set of goals, and we are vested in correcting the historic underservice to certain minority groups, then you get that sense of ownership…that then creates success.”

A student gets familiar with test tubes, acids, and bases during a hands-on activity.

She goes on cite a scenario where a kindergartener participating in the program now might feel ownership down the road: “They were there the day we talked about density, so they know that matter has different qualities, that not every cup of water weighs the same. So when they get to chemistry when they’re in eighth grade, it’s not going to be 100% new, and they’re going to feel that ownership.”

Bravo believes that another impact is that the students are getting the message that they can follow in their SACNAS role models’ footsteps: “'You can do it! I’m Hispanic, like you, and I’ve come from the same places as you, and I’m being successful at what I’m doing so far.' So I think everyone is capable of doing whatever they want, even if it’s something as complicated as science.”

Harris says all of the participants, including the grad students, have benefitted.

“So it’s been great,” remarks Harris, “because it’s been beneficial to everybody involved. Obviously for our program and for our parents and our students’ needs, it’s been really great. But then, also, for them [Illinois students], it’s been fostering leadership and opening up the area of education to a group of people that previously didn’t really think about education—working with kids and such.”

More: Cena y Ciencias, K-6 Outreach, Leal Elementary School, SACNAS, Underserved Minorities, 2015

For another I-STEM article about Leal School and SACNAS see:

Left to right: Brenda Andrade, Sandy Perez, and a couple of Cena y Ciencias participants. Andrade explains about having the students performing tests with ph paper during the lesson about different tools for observing chemical reactions: “We were mixing different acids and bases and getting reactions. Now, these are things that they can see, so it was either gas-forming reactions, color-changing reactions. So the visual thing is so that they see that something is happening, but they were also using ph paper to see the difference. That’s to demonstrate to them that even though we can’t see something happening, the ph changed.”

.jpg)