MechSE’s Amy Wagoner Johnson Teaches Grad Students How to Communicate Their Science

“Science isn’t finished until it’s communicated. The communication to wider audiences is part of the job of being a scientist, and so how you communicate is absolutely vital.” – Sir Mark Walport

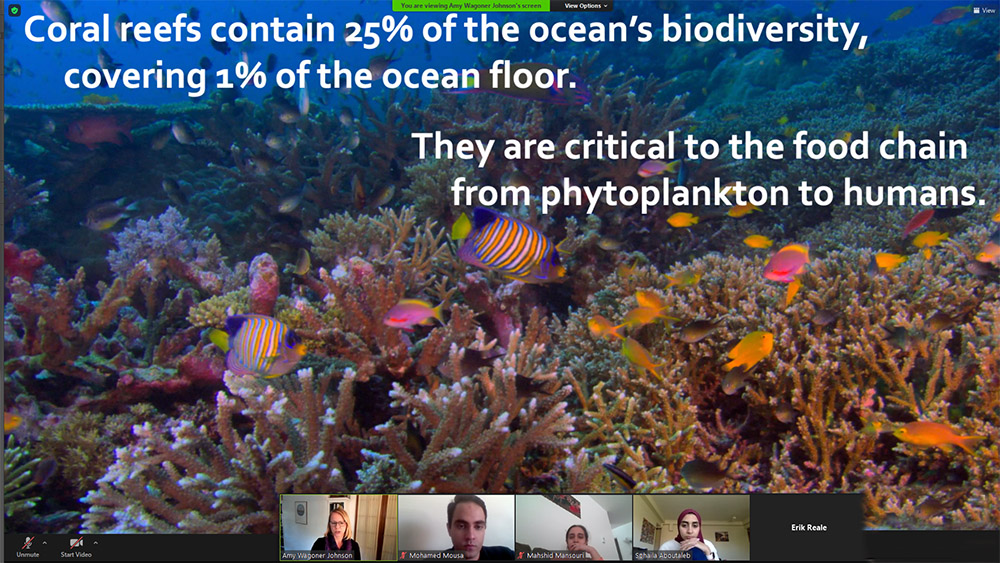

MechSE Professor Amy Wagoner Johnson interacts with her ME598 students via Zoom.

October 12, 2020

The above assertion by Sir Mark Walport, Chief Scientific Advisor to the UK government, is a favorite quote of Mechanical Science and Engineering (MechSE) Professor Amy Jaye Wagoner Johnson's. In fact, it might be considered the philosophy behind her ME598 AWJ Science Communication course. A while back, she decided that one aspect of graduate students’ education that was sadly lacking was communicating their research—both to colleagues, fellow engineers/scientists, and to Joe Blow (or Josephine), the average citizen on the street. So she began to explore science communication, augmenting her own knowledge and skills, then passing them on to her students. Today, the Science Communication aficionado teaches her course to grateful graduate students who count it a crossroads on their journey to more effectively communicating their work.

The Fall 2020 semester is the second time the MechSE professor has taught the course at Illinois; the first time was spring 2019, when it was a one-semester, 4-credit-hour course. However, beginning this fall, it’s a two-semester continuation course: two credit hours in the fall and two in the spring. Why make it longer?

“For science communication,” she explains, “I feel like sometimes you need time to develop, and I thought it could be interesting to give them a bit more time to develop. They're doing a portfolio where they have four elements to it, and this would allow them to do some things that could be a little bit more sophisticated than if they only had one semester.”

Rishee Iyer responds to a fellow student's suggestion as to how he might improve his presentation.

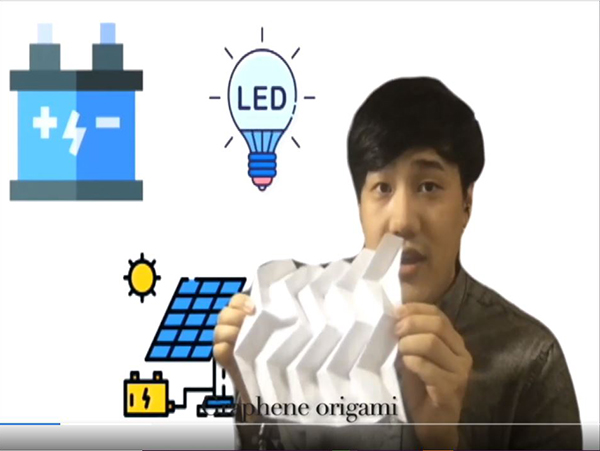

As sophisticated, for example, as the video she figures some students might want to include in their portfolio. Thus, she recommends that they turn that one in at the end of next semester “so that they have more time to learn about it, and they might have a better product at the end.”

Wagoner Johnson believes the portfolio gives an indication of the breadth they’re covering in class. It has four components: two are oral, and two are written, and not only that, but two components are directed toward a lay person, while the other two are directed toward a technical audience. (This reporter lauds that provision, having sat through many a talk replete with scientific jargon that zoomed right over my head.)

While students’ portfolios must meet the above stipulations, Wagoner Johnson insists the overarching goal of the course is that they “choose what is going to be most useful to them.” Students can include any combination in their portfolios—a short written technical report and a long, lay audience oral, for example—as long as they satisfy the four elements. “So that gives them flexibility to really try to learn a lot about these different types of communication,” she acknowledges “but also to end up with something that's useful to them.”

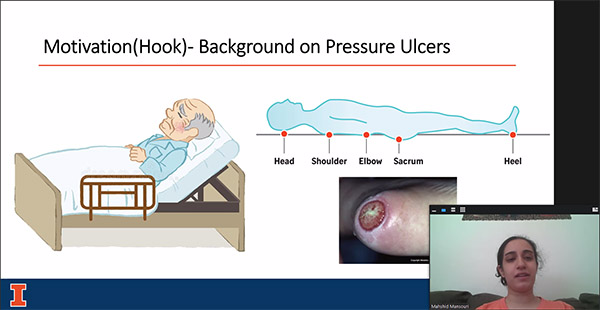

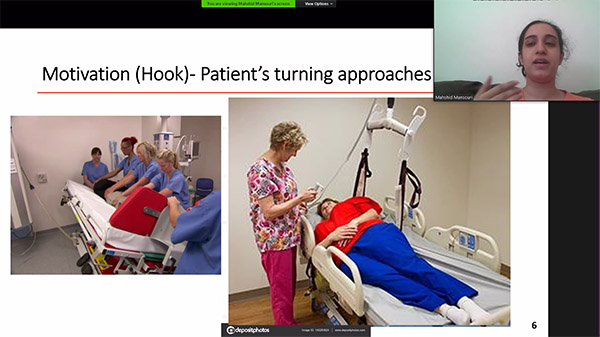

Above and below: MechSE grad student Mahshid Mansouri, who works in Professor Elizabeth Hsiao-Wecksler's Human Dynamics and Controls Lab, presents two slides that are part of the "hook" (how she is connecting with her audience) in her presentation about her research titled: Autonomous Morphing Bed Mattress for Patients with Limited Movement Ability.

Regarding students netting something useful, she shares an anecdote about how four or five students wisely took advantage of this proviso the first time she taught her course. Going to the same conference at the end of the semester, the students worked on their presentations for the conference as one of their portfolio elements. “And the timing was just perfect,” she admits, “because we worked on those a lot. Then the semester ended, and then 10 days later, they went to the conference. I also happened to go to the conference, and so I got to see them do their presentations in front of the real target audience. So that was pretty cool. So that's kind of the final product that they get from the class.”

Her course covers numerous communication techniques. For instance, the first day of class, she had them “sit there and write an abstract from scratch. ‘Just write it right now!’” She didn't grade it right then, but encouraged students, as they learned different writing strategies and began formulating their idea or their story strategies, to revise their abstract, which they've revised once or twice now.

Having also addressed writing mechanics in class and given students a checklist of common writing issues, she’s having students read each others’ abstracts and identify some issues. “This phrase is redundant, or this term you're using is elevated, or imprecise, or not specific enough,” she explains. “And so that gives them a chance to see these kinds of things in someone else's writing, because I feel like it's easier to see it when somebody else writes it than when you write it. And so the idea is that, hopefully, through that exercise, they will also be able to see that in their own writing, which will help them make a better product.”

Another form of communication she addressed this semester was elevator pitches. First, she had students work on one of their own, then record it. After watching a video of somebody critiquing elevator pitches, students were to identify some mannerisms or problems with their pitch, then rerecord it. Then they talked to the class about it, answering “What did they learn about their own communication when they were seeing themselves give their elevator pitch?” Wagoner Johnson calls the exercise “Really interesting. A lot of them were assessing themselves and trying to identify for themselves what their issues are in terms of communicating their ideas.”

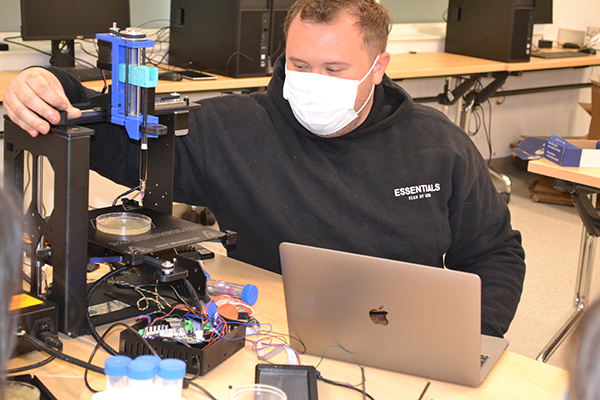

Erik Reale, a MechSE grad student who is a researcher in Assistant Professor Kyle Smith's lab, comments on a fellow student's presentation during ME 598.

Regarding the need to improve one’s writing, Wagoner Johnson recalls personally dealing with that issue. “That was something that I really struggled with when I was a new assistant professor,” she admits. “I worked really hard on a proposal, and I gave it to my mentor, and he handed it back and was like, ‘I have no idea what you're talking about!’ Though she responded, “Are you serious?!” (to herself, of course), she confesses, “That made me realize, ‘I have to look at this differently,’ because here I had this great thing I was giving him to read, and really it just wasn't what I thought it was.”

Given her personal experience, she’s picked up a few tricks she tries to pass on to her students. One is this: they really have to feel like they're looking at their work as someone else and not themselves—trying to see it from someone else’s perspective. “If you can keep this in mind,” she exhorts, “then this is going to help you in any kind of science communication or other communication.”

Another stratagem she emphasizes, somewhat similar to the above, is empathy. “I talk about empathy a lot, and I really believe that if they can have empathy for their audience, and know their audience, then they can go pretty far in their ideas about how they're communicating their science.”

One scientific communication guru Wagoner Johnson admires, whose principles she has studied extensively and adopted into her own strategies, is Alan Alda. She credits him for both the empathy emphasis plus another technique she intends to employ with her students during the course—improvisation. “Alan Alda does improv with scientists to get them to have more empathy in their communication,” she admits, adding that she would love to have Alda come, or even do a workshop with him herself. “He's so amazing. But in fact, the empathy idea is from him; I have to give him credit. He has a book where he really talks about empathy, and how that's important to science communication.”

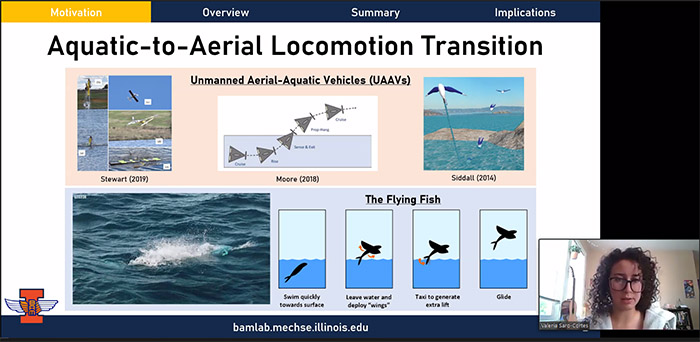

MechSE grad student Valeria Saro-Cortes, who works in Professor Aimy Wissa's Bio-inspired Adaptive Morphology (BAM) lab, presents her research, which is motivated by the development of an Unmanned Aerial-Aquatic Vehicle capable of locomotion in both water and air. It's bio-inspired by a flying fish, a creature capable of transitioning seamlessly from high-maneuverability aquatic locomotion to long-distance aerial travel.

Taking a page from Alda, she plans to do the following improv exercise with her students: to put the titles or names of different people or roles into a hat and have students draw names, which could range from Diane Marlin, the mayor of Urbana; to an NSF (National Science Foundation) program manager; to an 11-year-old student at Urbana Middle School who is not interested in science; to one’s grandparents. After taking a few minutes to gather their thoughts, maybe even looking something up about that person, students have to go around and say, ‘Okay, my person is Diane Marlin, and she's the mayor of Urbana.’ Then they will give their spiel about their research, answering several questions, including: What are the interests of this person? Why would they want to hear about your science? What is your goal in talking to them about your science?

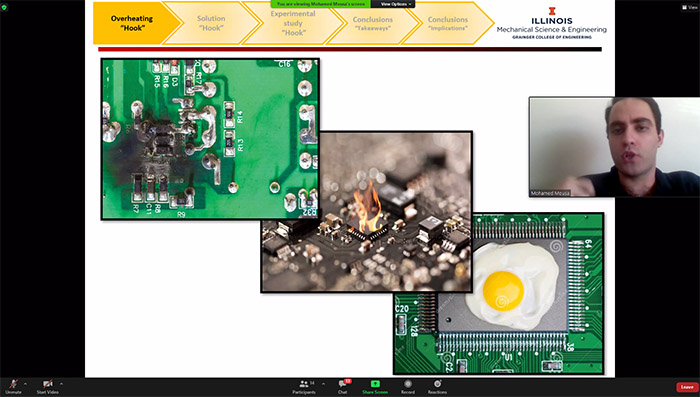

MechSE grad student Mohamed Mousa, who works in Professor Nenad Miljkovic's lab, shares his "hook" about how electronics can overheat in an effort to educate his audience about the evaporation field in heat transfer.

So how did Wagoner Johnson get interested in scientific communication? A scientist herself, she studied material science as an undergrad, then got her PhD from Brown in engineering, with a major in material science and minors in solid mechanics and applied math. So she’s undoubtedly called upon her knowledge in the area to improve her own presentations about her research in the areas of biomaterials and biomechanics or applications related to health (bone repair and regeneration and preterm birth) and the environment (coral regeneration restoration).

However, her passion for the subject was mostly born out of frustration at having to repeatedly cover the same ground when mentoring her own graduate students. “I felt like I had to teach them how to write and how to give presentations,” she admits. “And it was really frustrating, because I felt like I was teaching every single student…I felt like I wasn't well equipped to do it, and it just felt so inefficient.” So she applied for a grant and had a famous engineering science communicator, Michael Alley, come and do a workshop on scientific presentations, which she says was a big success.

In her presentation, "Engineering: How Math and Science Can Be Fun," MechSE grad student Kellie Halloran uses a clip about the Flux Capacitor from Back to the Future, Part 1. She hopes to intrigue the K-12 audience she's targeting with the idea that engineering can be innovative yet fun.

While the Alley workshop was a one-time shot, she acknowledges that, over the years, she began to realize that all of her hard work was paying off. “I found that my students who graduated would contact me, and they'd say, ‘I'm so glad that you made me work so hard on that paper, because now, when I write reports for my boss, he uses my report as an example. And it was really hard when you did it, but now I'm really glad that you did!’”

In fact, she shares an anecdote about a student who had gotten his PhD then went to Notre Dame to be a professor. An undergrad he was mentoring wanted to come to Illinois to do the same exact thing that he had done…have the same advisors and everything. When she arrived on campus, the undergrad relayed to Wagoner Johnson what her Notre Dame professor had told her—that his former Illinois professor had been really rough on him for writing. “So that's what I want!” she had declared.

MechSE grad student Sohaila Aboutableb, who is conducting a bone scaffolds research project in Wagoner Johnson's lab. Her goal is to maximize bone growth in the scaffolds after implantation.

“So I got this feedback that my students were valuing that,” Wagoner Johnson recalls. This prompted her to study it more in depth, then ask if she would be allowed teach a course like that.

“I think, more and more, people are really understanding the importance of science communication and are valuing it. I think that probably 10 years ago, if I'd have proposed to do this course, I'm not sure it would have been very well received by people who assign the courses in the department.” However, she says that now, there’s a lot more emphasis on science communication. “So I think it's valued more,” she reiterates.

Wagoner Johnson admits that she finds the course quite rewarding. In addition to having fun herself, she claims, “I just saw this kind of transformation of some of the students; some who started didn't have a lot of confidence, and I saw that change over time."

To improve her course, she did an end-of-the-semester survey, asking students about every activity they had done: “‘Did you value this? Would you recommend that I do this activity again?’ I asked them to be really honest,” she says, “because if I teach it again, I want to know, did this work, or did this not work?” Wagoner Johnson got a lot of positive feedback. For instance, some students said every grad student in MechSE should have to take this class.

MechSE grad student Sohaila Aboutableb shares her future steps at the end of her presentation.

Regarding another student who defended his thesis a few months after taking her course, a colleague on both his preliminary exam and thesis defense committees reported seeing this big change between his prelim and his defense. He had completely changed how he was presenting his science, which was really complicated to talk about, comprising huge amounts of data. Acknowledging that some topics are hard for people to relate to, Wagoner Johnson says those students have to work a bit harder to make it super interesting to other people. “So I was pleased to hear that he did a good job of changing the way he was doing things.”

Wagoner Johnson’s course is geared toward PhD students, not Master’s, “because I do want them to get into technical detail, and I want them to have gotten far enough into their research projects that they really have something they can talk about in detail.” She wants them to know the background, plus have done literature reviews, experiments, and/or computational work, “so they have some results that they need to find a way to present in a way that tells a good story.”

ME598 student Tawfiqur Rakib suggests to the student who just presented ways to improve their presentation.

Why is it important to emphasize scientific communication? Walport's “Science-is-not-finished-until-it’s-communicated” statement above might be considered Wagoner Johnson's credo.

“So that depends on what your goal is,” she claims. “And for many academics that means writing a paper, but more and more, the same is true for other audiences, like the lay audiences. And so I would say it's almost like you really haven't even done anything if you haven't communicated it to someone outside of your advisor.”

For one, she believes it’s important for developing policies that can help in healthcare and in the environment—those kinds of applications. She says science communication is also crucial to help populate the STEM pipeline. “It's important to get kids excited about science so that we can have more doctors and engineers and scientists who are taking care of people and inventing things that can help people and the environment,” she insists.

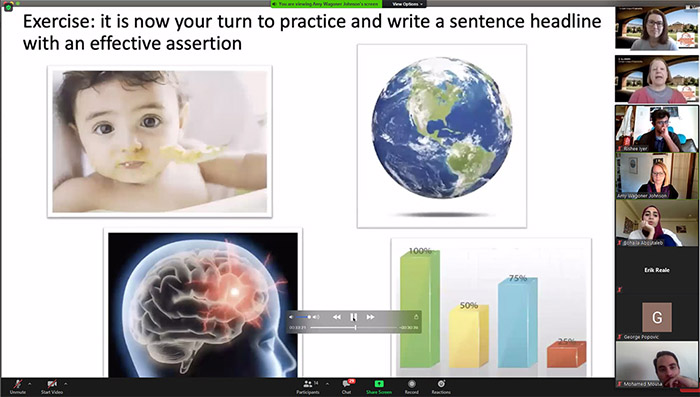

During Amos and Brunet's video, Wagoner Johnson paused the presentation to allow her ME 598 students to write an effective assertion.

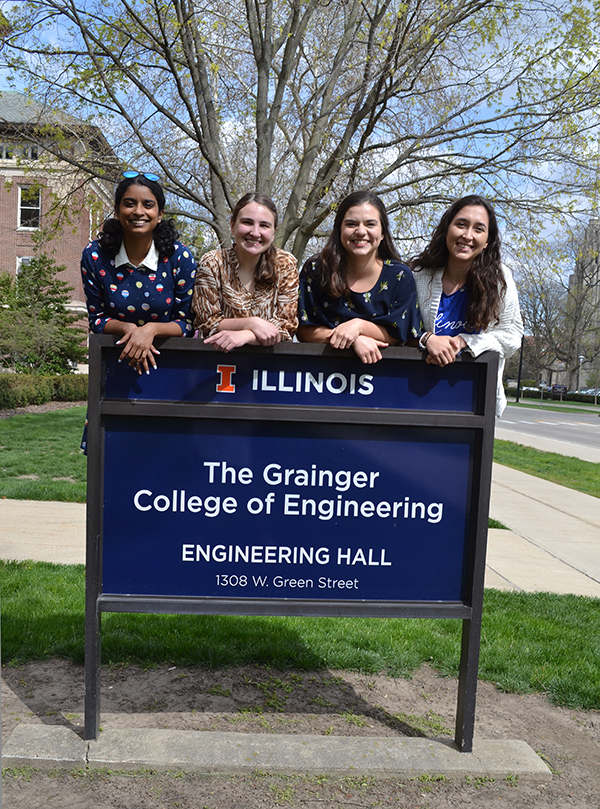

On a final note, in addition to Alan Alda and Michael Alley, the science communication experts acknowledged above, Wagoner Johnson gives a shout out to Engineering's Jenny Amos and Marie-Christine Brunet and their Assertion, Evidence-Based Presentations teaching developed for their work with the Grainger’s Engineering Ambassadors. In 2019, they presented to her class, and this year, she will present their recorded version. “I feel like this is a really important part of the students learning how to make effective presentations,” she asserts, “And so I just wanted to make sure to give them credit for that because I really rely on the way that they present this idea, and I really appreciate their efforts. My efforts on that would not be as effective if I didn't have their contributions to that.”

Author/Photographer: Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: Faculty Feature, MechSE, 2020

For additional I-STEM web articles about MechSE faculty, see:

- Local Children “Make” Nanodiamond Molecules at the Orpheum Courtesy of MechSE Professor Lili Cai

- Mattia Gazzola’s Paper2Tree: A 3-Step Program to Give Back to Your Community: Publish a Paper ➜ Plant a Tree ➜ Perform a School Outreach

- MechSE’s Joe Muskin Enlightens Local Youngsters About 3D Printing During Champaign Public Library Event

This slide Wagoner Johnson presented during class is an example of the Assertion/Evidence style; the statements at the top are her assertion; the large image of a coral reef and the many sea creatures inhabiting it is her evidence.

.jpg)