Next Generation School Pilots Project Lead the Way Elementary Curriculum

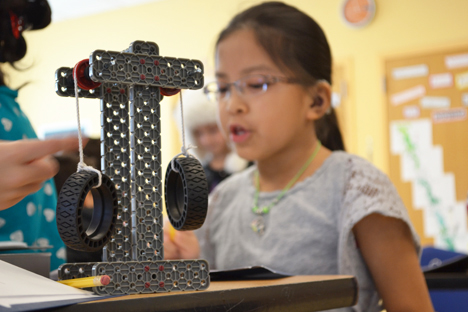

NGS kindergartener displays the structure she built as part of the LAUNCH unit.

November 20, 2013

When the Big Bad Wolf shows up at the Three Little Pigs' houses to huff, puff, and blow them in, some Next Generation School kindergarteners concerned about the porkers' plight might now be able to do something about it. With the engineering principles learned through LAUNCH, Project Lead the Way's (PLTW) pilot program for elementary students, kindergarteners attempted to construct houses able to stand up to gale force winds (or a box fan, at least), thus ensuring the swine's safety.

One of 44 schools nation-wide who are testing the program, Champaign's Next Generation School (NGS) is piloting the program and giving PLTW feedback. The basic idea of LAUNCH is less teacher-directed, more kid-directed, problem solving.

Kathy Feser, the master science teacher for grades K–5, says the curriculum teaches children to solve problems using a basic engineering design process: Ask, Explore, Model, Evaluate.

"Basically," explains Feser, "we're taking elementary school students through this relatively formalized process where they're asking questions; they're exploring information that we're able to give them; they're able to build physical models of something; and then they're testing them in some way and deciding if they have answered the question."

NGS science teacher Kathy Feser helps a kindergartener test her structure in front of a box fan.

For more kid-friendly learning, PLTW frames the problem within a story. For example, the Kindergarten unit: Structure and Function, addresses structures in two classic children's stories, Jack and the Beanstalk, and The Three Little Pigs, for which children were to address the questions: "What does structure mean?" and "What is the function of the structure?"

Feser describes the thought processes she and her kindergarteners used: "What was the structure of the beanstalk? Tall, strong, climbable. What was the function? To get him from place to place." Then, based on their analysis, students used pipe cleaners to build a tall, strong beanstalk that would hold a golden egg.

How did the children do? While PLTW's website says of its curriculum, "Students learn important, future-changing lessons, like it's okay to take risks and make mistakes," according to Feser, her kindergarteners struggled with the "it's-ok-to-make-mistakes" part. "Not everybody feels like they've created something that they are proud of," she admits.

NGS kindergartener proudly points to the second story of his structure, which withstood the box fan test.

However, this is one aspect of the curriculum that she likes—just like in real life, sometimes one fails. "I think that's one of the good things about Project Lead the Way—is that it is challenging." She continues, "It's not a warm, fuzzy curriculum. I think it is challenging for the children to a point where there is sometimes frustration, but we just keep saying, 'That's ok. All you can do is try.'"

For the "Three Little Pigs" section, children performed the same analyses. Then each constructed a house made of straw, sticks, or bricks, which they then tested in front of a box fan. Those whose houses "blew in" went back to the drawing board, then were given another chance to test their house.

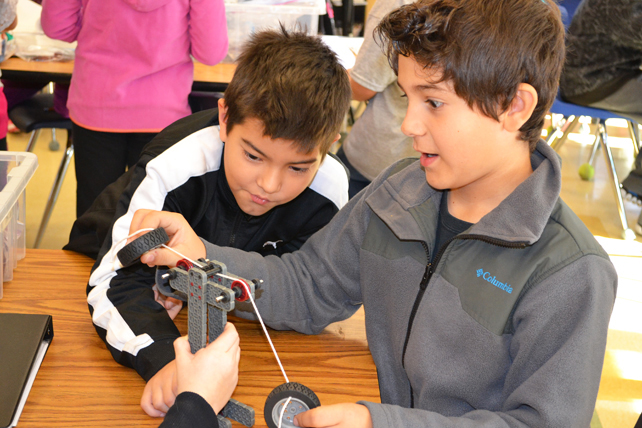

Fourth grader prepares to test the pulley to discover which works better: two pulleys or three."

The unit for fourth graders, Energy: Collisions, is also story-based. Students are introduced to three children in a bumper car. First, the unit addresses simple machines: a lever, pulley, and an inclined plane; then potential and kinetic energy; and finally, collisions. Then, using VEX kits, students must design a vehicle that protects an egg, which will be tested on an inclined plane.

Finally, after learning about insulators and how heat travels in the Materials Science: Properties of Matter unit, 2nd graders will be challenged to keep ice pops cold for a soccer game.

So how does PLTW's strong STEM emphasis benefit kids who aren't necessarily interested in STEM careers, but who are interested in maybe music, the arts, or writing? Quick to acknowledge that all kids may not be interested in STEM, but Feser believes they can still benefit from the curriculum.

"There are a lot of kids that maybe…science and technology doesn't necessarily float their boat. But you have to be able to solve problems. Whether you are going to be a scientist, or you are going to be a dancer, or you are going to be a minister, if you are living in the real world, you are solving problems. That's where I think problem-solving curriculums are really exciting. Some kids may not get excited about science, but they can still see why it's exciting to solve a problem."

NGS fourth-grader builds the pulley for the PLTW unit on Energy: Collisions."

Chris Bronowski, Head of School, also loves the problem-solving aspect of the curriculum: "I think that one of the things that is really neat is to watch the students go through the process. I was in the classroom and they started building their beanstalks. I watched this little girl, and she kind of had her ideas drawn out and just this intent focus of building, constructing. Then I watched her sit back, look at it, take the whole thing apart, and start again. But it wasn't like, 'Oh, I have to take this apart again. It's not right.' That's what I love about it."

Another thing Bronowski is pleased with? The fact that the curriculum is aligned to the CORE and the soon-to-be-released Next Generation Science Standards.

"That's one of the things we love about, is that it's so well researched. It's been our experience with the middle school curriculum as well, that Project Lead the Way, as a whole, is really well researched, well developed, and very thoughtfully designed, and they do their very best to make it accessible. They are continually reflecting on the curriculum that they provide so it's fluid in that sense. They make it easier for teachers to implement."

VEX pulley the fourth grader in the background and the rest of her team built for the PLTW Energy: Collision unit.

So how did NGS end up being a pilot school? After hearing a while back that the elementary curriculum was in the works, Bronowski lurked on the PLTW site and applied the minute she discovered that it was available. No doubt the fact that the middle school uses PLTW's curriculum also contributed to their being chosen to pilot LAUNCH.

What's it like being a "guinea pig"—testing a program that doesn't necessarily have all the "kinks" worked out, but may change as a result of pilot schools' input? Bronowski is used to NGS being on the forefront.

"It's really exciting, because it offers us the opportunity to be on the cutting edge, which is something that we are always doing and always looking for new ways to reach our students. So, in a lot of ways, we are the guinea pig, but we're just doing what we always do."

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: K-6 Outreach, Next Generation School, Project Lead the Way, 2013

Two fourth graders analyze which works better for lifting the tires: two pulleys or three.

.jpg)