Building a Bridge to a Better Tomorrow:

The 2018 National Student Steel Bridge Competition

A member of the Kenesaw State team helps construct their bridge on Bardeen Quad.

June 1, 2018

Would you participate in a national competition to build bridges simply for braggin’ rights? Barkin Kurumoglu, the National Co-director of the 2018 National Student Steel Bridge Competition (NSSBC) and a student here at the University of Illinois, certainly seems to think so. He claims “The unspoken goal is for schools to show who is better at civil engineering.” Lafayette College walked away with that honor, followed by California Polytechnic State University - San Luis Obispo in second place, and École de Technologie Supérieure in third place. The participants of the 42 teams in this year’s competition came from all over the nation, based on their scoring in the regionals. Plus, the competition should possibly be renamed the International Student Steel Bridge Competition, given that a number of teams were from other countries, such as Canada, Mexico, and China, along with one from the U.S. territory, Puerto Rico.

Barkin Kurumoglu, the National Co-director of the 2018 National Student Steel Bridge Competition.

Kurumoglu himself hails from Turkey, where he organized events for his high school Model UN team. He credits that experience for landing him his current role of being in charge of administration for the NSSBC competition, which was hosted on the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign campus this year. He worked with the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) board to handle logistics for the competition and provided an organizational perspective, while his co-director Jacob Cross was on the Steel Bridge team and worked from that standpoint.

Kurumoglu's passion for his role is obvious: “I genuinely enjoy putting something together for other people to enjoy,” he says. He believes that while some may avoid it due to the sheer amount of responsibilities involved, he is driven by the thought that when the event is over, the 650–700 people who attended will look back on the occasion as a solid affair, whether they are locals from the University of Illinois Civil Engineering Department or come from countries as far-flung as China or Latin America.

A member of the NYU steel bridge team paints their bridge with finger nail polish.

The competition itself is sponsored by the ASCE and the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC). In fact, the NSSBC started out as a student organization that was aided by the ASCE and the AISC and eventually evolved into the competition that has been running for at least 30 years now. The purpose is to build a bridge based on guidelines prepared by the American Institute of Steel Construction (AISC). The bridges are usually 3 by 17 feet, which is so big that even though they're brought to the competition as parts, most schools have to use trucks to drive them down. Some even ship their bridge, or as in the case of the California State Polytechnic University, Pomona team, fly their bridge to the competition.

The participants were primarily from civil engineering programs, although students who are not studying CE but simply find the subject matter interesting are also welcome to be a part of the event. The competing teams are usually 8–10 builders, but a lot of schools bring their entire Steel Bridge team for a fun time.

In the first event of Saturday's competition, the "Speed of Construction" category, the “builders” only have their tools to aid them as they race against the clock to put them together. The actual event involved running to and back from a box containing the parts. The building time is multiplied by how many builders are on the team, so it is in the team's best interest to have the fewest builders while still ensuring they can complete the task at hand. The New York University team used just two builders to capitalize on this rule.

Two judges (right) watch to ensure that no team members from the District of Columbia step into the "river."

Also, teams could get penalized if they dropped a part on the floor because the competition simulated the bridge being built over water, in which case dropping a part would mean losing resources like the money invested in acquiring that part. Even walking on the blue tarp that denoted the river meant that builder “died” and could not help his team build anymore. Kurumoglu jokes that we should think of the water as lava like in the ‘floor is lava’ childhood game.

The Illinois bridge team adds weight to their bridge for the vertical load test.

Other scoring categories included weight, display, efficiency, economy, and stiffness. While schools do have some leeway in terms of what grade of steel they want to use and the exact kind of bridge they want to build, it does have to be made of steel. Kurumoglu did not think that it would be too beneficial to change the grade of steel, because each kind has its advantages and drawbacks. For instance, he commended the durability of the 904L, but said that it was harder to work with than the 316L, which is basically common stainless steel. The bridges are subjected to a lateral load test to measure stiffness, wherein the bridge cannot deflect past a certain point or the team gets penalized. They also undergo a vertical load test in which the bridge has to hold 2500 pounds. For the economy score, judges made an economic calculation based on the building time, and construction and maintenance costs, as well as an analysis of the costs and benefits of the project.

A member of the Milwaukee School of Engineering steel bridge team attaches a weight onto his bridge for the lateral load test.

The bridges were assembled twice, with the first time being on Friday afternoon, May 25, 2018 on the Bardeen quad, where the teams explained their process in reaching the end-product. The judges walked among the displays and gave points based on the design's aesthetics and the poster board presentations brought by the competing teams. The second time was on Saturday, May 26th, when the teams started early in the morning and set up to present depending on a preset competition order with assigned time slots.

Paige Oursler ( in the front row on the left) and her teammates on the Missouri S&T Bridge Team.

What is the appeal for students in participating in the competition? Paige Oursler, a senior in Mechanical Engineering at the Missouri University of Science and Technology, whose team placed first among the 13 teams at their regionals, lauded the hands-on nature of the competition. “You actually get to go out and do different things." she says, "You get to make things; you get to build; you get to design.” She believes that participating in such events gives students a leg up both in the classroom, when they learn concepts that they have worked with firsthand, and in real life, because they begin to understand the technical jargon engineers use in the industry every day.

Her teammate, Alex Schull, a senior in Civil Engineering and in his second year on the team, agrees, calling being on the team "an add-on to what the classroom had, a little reinforcing.” He believes that not only does participating in such events garner name recognition of their school from attendees and the other schools at the event, but it also shows that students at their university can actually apply what they learn in the classroom.

This was a common theme for many participants. Jacob Harris, a rising senior in civil engineering at the University of North Carolina-Charlotte loves working with his hands and credits the steel bridge team for “a way [for me] to learn a new skill involving welding and milling.”

Charlie Carter, AISC judge.

Even Charlie Carter, who works for the AISC and has been judging the competition for the past decade, cites the biggest benefit for students being that the competition is closer to real-life scenarios than anything they will face in the classroom. He points out the various innovations students have come up with, like creating special tools for this specific event or using the sliding dovetail, an old trick in woodworking that allows parts to just slide together and lock. This is another way students learn from this competition, Carter says, where “Teams can look at each other’s designs and go, ‘Oh yeah, we didn’t think of that. That’s a neat idea, maybe we’ll do that next year.’”

NSSBC judge, Bart Quimby.

Bart Quimby, another judge at the event, has been attending the NSSBC in that capacity since 1992. He says he keeps coming back because “It’s just fun to watch college students—the intensity with which they do things.”

A professor of steel design for 23 years, Quimby realized that incorporating the steel bridge competition into his class added some spice to the course and got the students excited. He would work with students to design bridges in class and have the ASCE student chapter vote on which one they wanted to compete with. The next semester would be spent creating the bridge and competing with it. Quimby found that the reputation of the Steel Bridge team in the local town got to the point that having an employee who used to be a part of the team meant that you had a great worker. This motivated students to participate in the team, because having that experience on their resume gave them an advantage in the local workforce.

Judge and the director of education at the American Institute of Steel Construction, Christina Harber.

Christina Harber, the director of education at the American Institute of Steel Construction, was also a judge. She calls the NSSBC one of the largest student events they have all year with the most reach. While she is actually an Illinois alum, she was rooting for teams who were competing nationally for the first time. Harber was particularly impressed by the University of Puerto Rico, Mayagüez team, who has competed before, but made it to nationals this year despite having no electricity for months after the hurricane and a condensed school year.

Members of the Universidad Panamericana team show off their bridge.

One of the teams new to nationals was from the Guadalajara campus of Universidad Panamericana in Mexico. They placed first ahead of the 17 schools that competed in their regional competition, including schools from both Texas and Mexico. This is the first time on the Steel Bridge team for Neftali Ramirez, a third-year in civil engineering, who is one of the “builders.” She says that her most important takeaway from this experience had been learning how to work in a team.

John Duguil, a senior in civil engineering from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona.

This sentiment was shared by John Duguil, a senior in civil engineering from California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, who found that the collaborative attitude of the team transferred to the classroom. Having people to take classes with helped his academics, and he helped underclassmen in turn when they had questions. The team has become more like a family to Duguil, who calls it his community on campus.

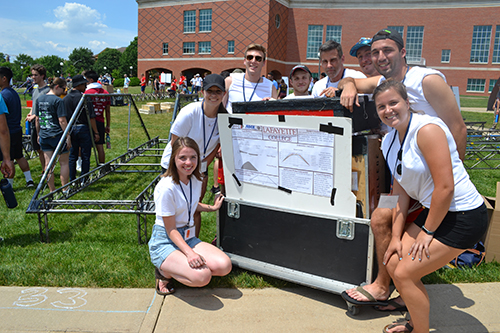

The winners of the National Student Steel Bridge Competition, Lafayette College.

The 2018 competition showcased the innovative perspectives of the next generation of engineers, while providing the students themselves with an outlet to explore their interests outside of a classroom without the fear of grades hanging over their heads. It shows how an extracurricular activity can go beyond augmenting classroom learning and in fact prepare students for the real world. The experience not only helped the participants develop their technical skills but challenged them to grow as creative thinkers and collaborators. Although it was only a two-day event, the days of work that went into creating the final displays show that the real achievement of the NSSBC is the spirit of determination it has instilled in its participants.

Story by Niharika Roychoudhury, I-STEM undergraduate student. Photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Civil Engineering, Engineering,

Undergraduate, 2018

Missouri University of Science and Technology steel bridge team with their bridge.

.jpg)