LaViers' RAD Lab Uses Robots/Dance to Study Movement, Provide Automation

“Human movement is a very complex thing, and we can’t create it in an engineering system. But we can start understanding it; that’s what we are trying to approximate.” Amy LaViers

September 8, 2016

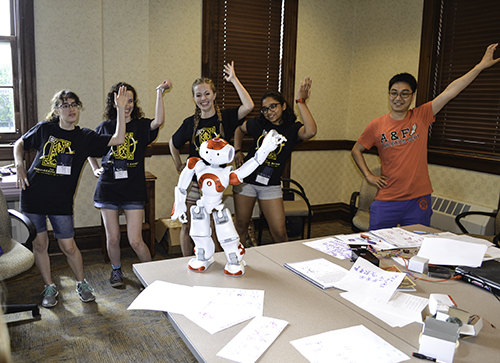

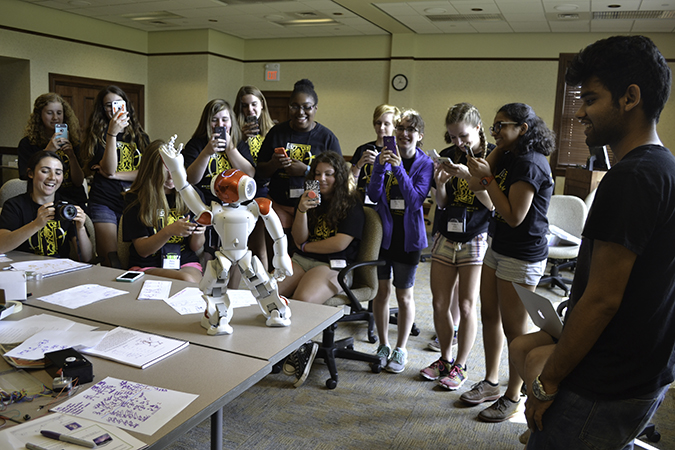

A team of GAMES campers, along with the RAD Lab grad student, Hang Cui (right), who had helped them with their choreography, form a chorus line beind NAO to do the routine with it.

Surrounded by a crowd of laughing, cheering GAMES campers, NAO, an adorable little white and red robot, strutted its stuff, doing the moves the girls had choreographed and which it had been programmed to do. Then, like a chorus line, the team of high schoolers who had developed the routine lined up behind NAO and performed it along with the robot, amid gales of laughter.

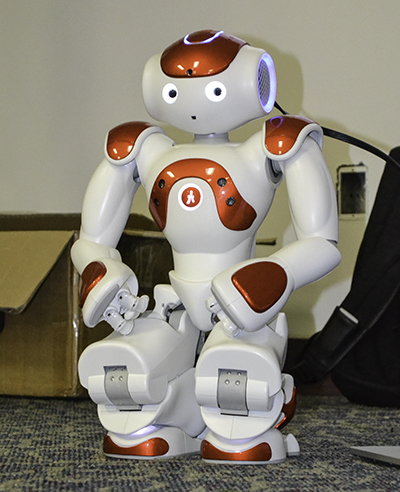

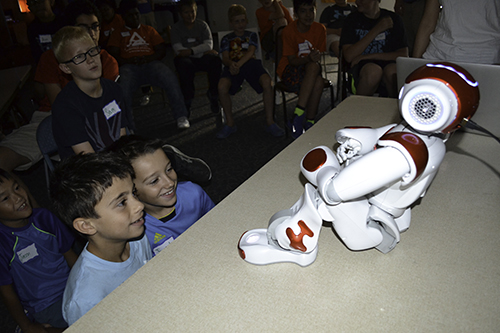

NAO waits in the wings to be presented at Ctrl-Z's robotics camp for local youngsters.

“People think it’s so cute!” admits Mechanical Science and Engineering Assistant Professor Amy LaViers, referring to NAO, the autonomous, programmable, humanoid robot her RAD (Robotics, Automation, and Dance) Lab uses in its research. Exhibiting the tendency people have to anthropomorphize robots, this reporter, who kept calling NAO “him," asked if they thought of NAO as a "him" or a "her."

“We prefer not to use a gender," LaViers stresses. "It is a machine. And we try to educate people about the fact that it is a machine. And the coolest thing about it is that you can design its movement!”

The fact that this little robot is programmable is what makes it valuable to LaVier’s lab. She says, “The GAMES camp activity was a little more interactive, and people could really see, “Yea, I can decide what it does. And that’s the power of robotics to me.”

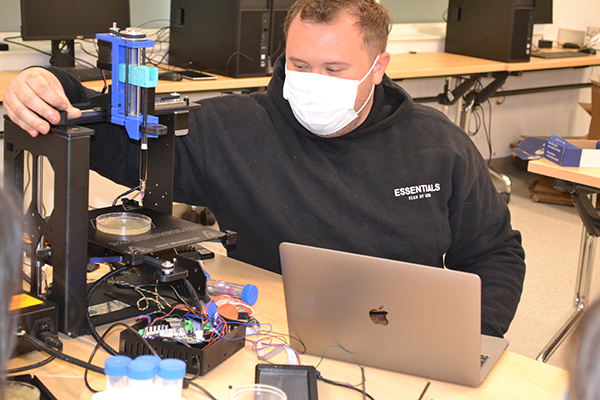

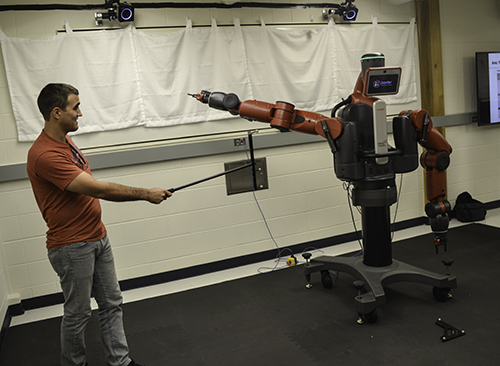

During RAD Lab's recent Open House, Eric Minnick, CEO of AE Machines, a young company that designs tools to make automation design accessible (and LaVier's husband) makes Baxter lift its "arm" using a wand-like electronic controller.

NAO’s "older brother,” Baxter, RAD Lab’s other robot, is not quite so endearing. Rather than legs, the much larger, more imposing robot, is attached to a pedestal with wheels. Rather than a “face,” it has a monitor (which I understand can be programmed with a sort of face, though). However, like NAO, because it’s a robot, it’s still intriguing to us humans. For instance, during RAD Lab’s recent open house on August 19th, visitors were tickled to be able to control both of the robots’ movement simultaneously using a wand-like controller.

“It’s surprising how interesting it is to watch them now,” LaViers says, regarding our fascination with robots, “because its movement is so much simpler than ours. It has so many fewer degrees of freedom and so much less control of the dynamic quality of movement. But, yes, people find it very interesting to watch. “

Young robotics aficionados express their appreciattion when NAO does something we humans do without even thinking, but which is a major feat for the little guy...sitting down.

Because of this fascination with robots, RAD Lab’s research lends itself to outreach activities quite naturally. In addition to the GAMES camp, the RAD Lab students did another outreach over the summer, where they demonstrated NAO’s capabilities to a group of robotics enthusiasts at a camp run by Ctrl-Z, one of FIRST’s local robotics clubs for 8th–12 graders.

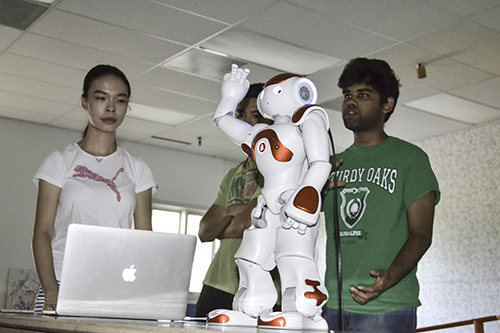

RAD Lab grad students present NAO to Ctrl-Z, a local robotics club for youngsters.

While the robots themselves are enough to pique one’s interest, another integral part of the lab is dance. Says LaViers, “I think there is a very natural connection between what we were just talking about, which is, ‘I get to decide how this machine moves,’ and 'What do we do in dance? We decide how other people should move.” What she’s referring to is the fact that in many types of dance, such as ballet, modern dance, even ballroom dancing, someone else often choreographs the movements of the dancer.

RAD Lab grad students take NAO through some movements during their activity with GAMES campers.

What interests LaVier is the process: “How a person might articulate a desired movement pattern or how we might transfer an existing process movement in a person to a very different platform—the simple robots that we have.”

And while their robots can currently do some standard moves based on the standard software that came in the box, the goal of LaViers’ research is to improve the software, to enable the robots to perform more complex moves. Her mission? To “design algorithms for robotic control” says LaViers, to “leverage existing tools in order to create high-level, supervisory controllers that define more complex behavior."

LaViers says her lab uses use a number of tools—mathematics, supervisory control, optimal control, and information theory—to conduct their research on movement, But one of the main tools they use to describe movement is a taxonomy called Laban-Bartenieff studies, which she describes as “a very compact and descriptive and qualitative language that people use to describe and analyze movement. It’s a formalized version of a choreographer’s language.”

According to LaViers, Laban was a choreographer and Bartenieff was both a dancer and a physical therapist who worked with polio patients and people who were losing capabilities in movement. Bartenieff also worked with folks who had similar patterns of tension and limitations that were a result of their own training—ballerinas.

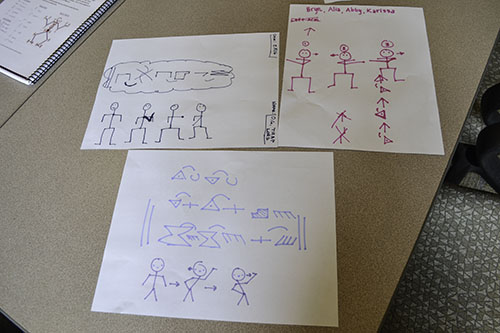

Routines the GAMES campers designed using the Laban-Bartenieff taxonomy.

During their recent Open House, one of RAD Lab's grad students, Umer Huzaifa (right), explains about their lab to a visitor.

During the activity she and her students did with the GAMES campers, they taught the girls some Laban-Bartenieff taxonomy so they could use it to describe the movements they wanted the robot to make.

“The activity is much richer if you don’t just say, ‘I want you to make up a movement phase, but I want you to name, and describe, and think about what is each movement, so that you can start to specify,” LaViers explains.

To further elucidate what she’s talking about regarding her research, she instructs me to make a movement by raising my arm up from my side to make a fist.

“The robot can’t do just what you did," she continues, "So we have to make choices about what is important. So that’s really where that training and that dance background that I have really pushed me into this direction. So hopefully people who do this outreach with us get a little taste of being conscious about what movements are.”

It makes sense that LaViers would incorporate dance into her research. She’s been dancing practically her whole life. She started dancing when she was three, and for most of her life has had at least one dance class a week, or been in companies which practiced several days a week. She was even involved with dance as an undergrad and during grad school. What kind of dance? You name it, she’s done it: ballet, tap, even modern dance and contemporary dance. “It was just always there,” she says. “It was just a natural connection with the work I was doing in robotics.”

So what is the connection between robots and dance? She and her team’s goal “isn’t to have dancing robots, although we would take that!” she admits. “But we are interested in creating lots of movement so that we don’t have a robot that does the same thing over and over again.”

Left to right: Baxter the Robot and Amy LaViers, on hand to both demonstrate and explain RAD Lab's research during their recent Open House.

Like robots in factories. “If you want to see a cool robot, go to a factory, right? We can make lots of cool things; we can control them. But they do the same things over and over again.” While she acknowledges that that’s the goal of a factory robot—“We are interested in that precision, because we want every MacBook to look the same”—she hopes to be able to program robots to do more complex movement. “But when we move those robots out of a factory for a human-facing scenario, the world changes more frequently. It’s more dynamic, and we need a lot more diverse movement capabilities that we can quickly access.”

What are some real-world applications for her research? LaViers says one would be manufacturing. She describes a couple of scenarios. The first is a BMW car factory, where “Every car is the same, and they make, let’s say, 10 million cars that are exactly the same. They are constantly in motion, twenty-four hours a day making these cars.” But what about a different kind of factory, where an order comes in from a customer who needs fifty cars that look a certain way, and then a month later, a different guy needs a different shape? “So there is a big nationwide push to move towards bringing automation into small-batch manufacturing.”

Understanding that a robot can do nothing without the software that controls it, the Ctrl-Z campers crowd around to get a peek.

LaViers says another application would be in coal mining or industrial cleaning, where every job is a little different. She says robots could be used to clean chemical plants, which are dangerous for people, and where there’s a lot of variability. For instance, these plants might come in different shapes and sizes, and the chemical buildup isn’t the same everywhere. There are many variables that come in to play. “It probably won’t be fully automated in the near future, in my opinion,” says LaViers, “but we can make them to assist the cleaners.”

Amy Oetting, an Illinois Computer Science grad student studying Human-Computer Interaction enjoys having one of her own with Baxter the Robot as she makes it move during RAD Lab's Open House.

LaViers says the Baxter robot would work in small-batch scenarios. Whenever a manufacturer wants automated or mechanical help in a complex way, a robot could be brought in and automated to do the job. However, she calls creating the specific programming “a fairly work-intensive process” that requires a lot of new tools.

Why are LaViers and her students involved in outreach? “Outreach is a very natural thing for the lab to do,” she says. In fact, she feels it’s her responsibility to do so, in order for the public to experience what “their” robots can do.

“We have really started from reminding ourselves who buys our equipment and who funds the research in the lab. In nearly every case, it is from taxpayer dollars…So I think about the burden we have to take care of the equipment and also the burden to try and share it with the people who it’s for, and who own it.”

LaViers admits that she and her team are also involved with outreach to recruit others into their field.

“We need people to be interested in studying this area, because we need more and more people—hopefully more and more diverse people that study this area.”

MechSE Assistant Professor Amy LaViers

And LaViers believes her research on robotics and movement is a great recruiting vehicle. She says it provides “an unusual inroad into very traditional engineering concepts. It is really fundamental stuff…So if you can become interested and take that class, for other reasons than just to play train or automobile, which is why a lot of students become interested in mechanical engineering…the very moving activity that we do is a very big piece of what mechanical engineering is. If you weren’t attracted before, you might be attracted through one of our types of activities or our approach to engineering.”

One of LaVier’s outreach goals for the future, in addition to doing GAMES camp again next summer, includes doing a robotics program back in eastern Kentucky where she’s from. She hopes to do a few workshops with them, then help them get a grant to buy their own robot.

“This is something that could engage a lot of students who don’t get that kind of exposure there. And whenever you go back home you always feel that you should be helping the place, and I think that’s the next project I have….I want to find new areas and new neighborhoods where I can take this, and that is my goal.”

Author/Photographer: Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

For more related stories, see: Faculty Feature, FIRST, GAMES, GBAM, Graduate STEM Outreach, K-12 Outreach, MechSE, Women in STEM, 2016

Amy LaViers (right) works with a team of GAMES campers to help them troubleshoot the routine they choreographed for NAO.

Amidst a frenzy of photo-taking, NAO struts his (whoops! its) stuff for the GAMES campers.

.jpg)