Local 8th Graders Build Solar Cars Courtesy of New POETS' RET Curriculum

May 23, 2017

An eighth-grade student is working on building her solar car.

After spending weeks designing solar cars, teams of eighth graders at University Laboratory High School in Urbana and Next Generation School in Champaign tested their cars to see if they would move when exposed to bright light—then were either exultant or chagrined based on the results. The project was part of the POETS’ RET program, during which a team of four local science teachers was tasked with creating a multi-week curriculum unit related to power, heat, and power density that was aligned with Illinois’ Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS).

The teachers, Uni High’s David Bergandine and Sharlene Denos, Next Generation School’s Bryant Fritz, and Centennial’s Jay Hooper, were part of a multi-year effort to create an extensive unit. According to Joe Muskin, Education Coordinator for the NSF-funded POETS (Power Optimization for Electro-Thermal Systems) Engineering Research Center, the spring 2017 classroom testing at the two schools represented the first tests of some of the unit. After testing it in Denos’ class, modifications were made based on the outcomes, then it was re-tested in Fritz’s class.

Joe Muskin helps a student test her team's solar car.

This summer, POETS’ RET teachers (some returning, some new) “will refine the solar car module and add to it with new material as the entire multi-week curriculum is fleshed out,” Muskin explains.

The goal of this project, according to Muskin, is to “create a well-designed unit in which students problem solve, design, and engineer. We want the students to practice real analysis and to really think. We also want them to have fun and to see what engineering is really like—how it is a creative field where people invent new things to solve interesting problems!”

Muskin explains that as a result of completing the projects, “students gained a sense that they could design a solution to a problem and then successfully implement that design, seeing the results, and feeling that success as their cars worked with the available light.”

However, to get to that point, the process didn’t always go smoothly. For example, the motors didn’t produce enough torque to propel their cars with the limited light in the classroom. To generate enough torque to get their cars to move, they had to design a gearing system and print it on 3D printers. “They had to run some tests and calculate the gearing ratio they would need, then design a system to give them the needed torque,” Muskin explains.

A Uni High student tests the solar battery she's working on for their solar car model.

A Uni High student tests the solar battery she's working on for their solar car model.Since the lesson was first tested at Denos' class at Uni High, while students learned a lot, some of what they learned was through failure.

"Overall, I believe the lesson taught at NGS was much better organized and efficient, based on a great deal of troubleshooting my students did," she acknowledges. "That is one of the many benefits of working with Uni High teachers and students. We have the flexibility in our curriculum to experiment with projects like this and our students understand that it may not always work out perfectly. In this case, I believe the students learned much more from all the ways in which the car didn’t work. Students here are encouraged to take risks, which sometimes pay off, as with the multiple solar-panel limo, and sometimes do not, as with the cardboard, direct drive “racer."

Uni High students work on their solar car model.

Uni High students work on their solar car model.In some of the comments Denos' students made regarding the lesson, they confirmed that while they had learned a lot, they also learned through failure. For instance, one students said, "I learned what repetitive failure feels like, and I also learned how to operate the type of 3D printer that we used. I also learned more about friction, torque, and efficiency." The same student also indicates: "I think I learned many things while working on this project. I learned to be patient especially when my wheels kept on turning out to be unsuccessful, and I tried not getting mad at everything that didn't go my way—for example like the rubber bands weren't the right length."

Uni HIgh students test solar car components under a bright light.

A plan for further development and testing of the unit is in the works, to not only do it again in these schools, but to expand the development of the unit in the coming year to Champaign and Tuscola schools as teachers from those schools do the summer development then test in the coming school year..

Also, according to Muskin, teachers at POETS’ partner universities, Arkansas, Stanford, and Howard, will be helping to develop components for this extensive middle school curriculum.

One teacher, Bryant Fritz, who is experienced at writing curriculum aligned to the Next Generation Science Standards, was excited about participating in the project. “I know there is not very much curriculum in existence that really follows the standards well. And then the idea of incorporating electrical engineering possibly in the science content practices also, we thought that was really neat.”

Bryant Fritz helps his students test their solar car under a light.

Fritz indicates that for his students, the unit provided “just the right amount of challenge for them. They definitely learn throughout the entire time that engineering is a process of redesigning and refining and continuing to change things and solve problems as they go through the whole process. They definitely had their frustrations and they’ve learned that if they want to be successful with this, or in engineering in general, that they have to find ways to troubleshoot those things."

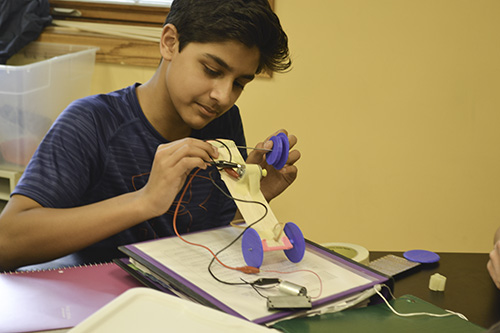

NGS eighth graders, Hadi Ahmad and work on their team's solar car.

Regarding the process and number of iterations students went through. Fritz admits, “we’re still going right now, with a few of them. I would say each group probably ran into a dozen problems that they had to fix, whether they were big things or small things. They had to go back and design the pulley; they had to change the sizes, reprint them, or try messing around with the spacing again. There were all sorts of possible things that could go wrong that they had to figure out.”

One of Fritz’s eighth graders, Hadi Ahmad, says the biggest challenge they encountered was “attaching the rubber band to this motor here and then putting it on the wheel. Because it was hard to decide how tight the rubber band had to be so that we could make it roll. If it was too tight, it would pull the motor, and it wouldn’t move, so I’m getting it to move. We’re still trying to overcome that problem, trying to get the rubber band to move the wheels.”

Evan Kuntz shares some things he learned about engineering through the project: “We have a lot of renewable energy sources like sunlight and that we could probably 3D print cars if we need to, which is kind of what we’re doing right now. If we could just make it much larger scaled, we could 3D print cars and make it much more affordable.”

Uni High science teacher Sharlene Denos works with her students on their solar car.

NGS eighth grader Abhinav Sattiraju reports encountering several challenging things. “After you put it all together, you have to decide after you test everything and see if it’s not working. That’s usually the case. You need to make several adjustments and you need to try different possibilities. After you finish it, that's the hardest part, because you need to make several adjustments to make it work.”

An NGS eighth grader, Tabeeb Khandaker, works on his team's solar car.

He also shares what he learned about engineering through this project, “I learned about speed and torque and the relationship—like more speed, less torque; more torque, less speed— things like that. Some little physics here and there. It's a lot of fun.”

Briana Bellard says she and her teammates, “learned a lot about how the gears function and how they work together. I feel like that was a big component of that. Learning about how to code and program stuff was really big too.” She learned to code in order to print in 3D. Bellard shares that as a result of this experience, she would most definitely pursue engineering.

An NGS eighth grader works on her team's solar car.

According to Banan Garada, the most challenging part was “probably trying to find the right wheel that wouldn’t fall off. Because a lot of the wheels kept falling off from it.” While they 3D printed the gears, the wheels were already printed for them.

Garada shares something she learned about engineering: “You can’t get things right from the first time. You have to keep trying. Don’t give up, keep trying and you’ll eventually get it.”

Anusha Muthekepalli says her team encountered numerous challenges: “There’s too many to count. There’s a lot of them. Some of them were easy to overcome, and some of them you have to fix the strength of rubber bands and there are a lot bigger problems that you need help on.”

As with many of the other students, Muthekepalli learned that engineering requires persistence.

“It takes more than one try," she acknowledges. "You just need to keep on trying. It doesn’t come easily. Sometimes you just have to ask for help, even if it hurts your pride a little bit."However, she evidently enjoyed it, because she says she will most likely end up pursuing engineering.

Two NGS students show off their solar car.

How’d the students do? According to Muskin, “There were so many different, yet well-working designs that the students came up with. The students saw that there isn’t just one answer, but as is often the case, so many interesting and creative solutions to a problem.”

Story by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, and Ashely Chung, undergraduate student, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photographs by Elizabeth Innes.

More: 6-8 Outreach, 8-12 Outreach, POETS, Next Generation School, RET, University Laboratory High School, 2017

For additional articles about POETS, see:

- POETS Seeks to Change the Attitudes, Shape of Students in the STEM Pipeline

- POETS, New NSF Center at Illinois, Poised to Revolutionize Electro-Thermal Systems

- National Science Foundation Award #1449548: Engineering Research Center for Power Optimization for Electro-Thermal Systems (POETS)

- POETS website

Two NGS eighth-grade students working on their solar car.

Two NGS eighth-grade students working on their solar car.

.jpg)