POETS Seeks to Change the Attitudes, Shape of Students in the STEM Pipeline

March 18, 2016

Andrew Alleyne, Professor in Mechanical Science and Engineering and PI of POETS

Andrew Alleyne, PI of the NSF-funded Center for Power Optimization of Electro-Thermal System (POETS), says the Center’s educational components are “all hypothetical at this point” and just “plans in people’s heads.” However, his plans and those of POETS’ Co-Directors of Education, Fouad Abd-el-Khalick (K-12 students) and Phil Klein (undergraduate/ graduate students), and Education Coordinator Joe Muskin appear to be well thought out and seek to strategically strengthen the education of targeted populations along the STEM pipeline.

Alleyne says POETS’ educational program is comprised of three strategic thrusts which target K–12, undergraduate, and post-Baccalaureate students and are designed to ameliorate certain weaknesses in engineering education for these targeted groups. In addition, the overarching emphases of all education components are to break down silos/foster interdisciplinarity, plus be sustainable, intergenerational, and engage underrepresented minorities.

Change K–12 Students’ Attitudes

POETS’ first goal—change K–12 students’ attitudes towards STEM—seeks to help students understand why STEM is important and relevant. Alleyne hopes to take the “mystery” out of STEM.

“At the very least,” he says, “we want it to be understood that it’s important and it’s not something to be feared. You hate to hear a person say later on in life: ‘I could never be an engineer because I was never any good in math or physics.’”

Here’s another mindset Alleyne and company hope to change among students who end up going into non-STEM fields: “Sometimes they tend to discount STEM as not relevant to them,” he admits. So one of POET’s strategies is to communicate to students early on that STEM is “important, valuable, nothing to be feared, and hopefully to be enjoyed, if you do it right,” acknowledges Alleyne.

POETS Educational Coordinator Joe Muskin teaching during a recent teacher workshop.

Joe Muskin, who is helping design and implement some of POETS’ educational components, says one K–12 program they envision for down the road is a Young Scholars Program. Around 2–6 high school students would come onto campus to do research in Illinois’ labs for several weeks over the summer.

Another program in the works, which would obliquely impact K–12 students, is a Research Experience for Teachers (RET), which Muskin calls “novel and interesting.” In traditional RET programs, teachers do complex research, then try to write curriculum around it. “Unfortunately,” Muskin explains, “what they try to take back into their classrooms is the procedure they did or the very specific thing that they worked on. Lots of times, it doesn’t really relate to the content they’re teaching.” So POETS’ RET will try to develop curriculum related to thermal and electrical processes that’s aligned to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). So the first two portions of the RET will be in-depth training on the NGSS followed by introductory lab experiences in several labs. “It’s not the depth, but instead it’s more of the breadth,” explains Muskin.

During the research portion, teachers will wrestle with, “How do we take something we really like, that we think would be aligned with the NGSS, and figure out how to do it in a classroom?”

For the first year, the RET would most likely be very limited: probably two teachers at each of POETS’ four institutions (Arkansas, Howard, Stanford, and, of course, Illinois). “We’re all going to try this out and see what works and what doesn’t work, and then we’re going to ramp it up for future years,” explains Muskin.

I-Shaped Undergraduate Students

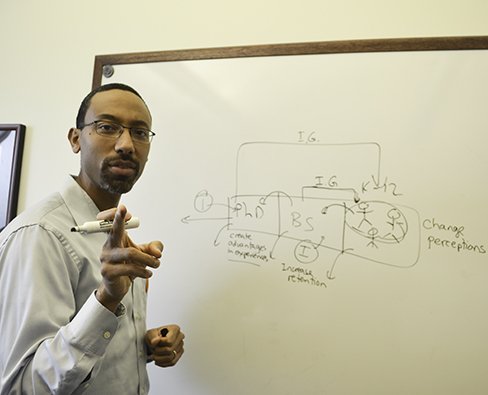

In teaching mode, Alleyne draws a model of POETS' three educational thrusts, how he'd like to shape each population, and the intergenerational "loop backs" he sees happening.

Alleyne's goal for the middle thrust, undergraduate students, is retention through interdisciplinary, sustainable, and intergenerational programs.

Alleyne describes his vision for undergraduate education as I-shaped: “Broad at the beginning, then they go into their individual departments and it narrows in the middle…then at the senior level you broaden out again and do interdisciplinary senior design projects.” To achieve this broader beginning, he proposes a more interdisciplinary, project-based freshman curriculum.

“There have been studies that point out if you silo people, they feel isolated,” he says. He goes on to explain that those in technical fields often don’t feel connected to the broader community. “There’s a segment of the population that, even though they are bright, they can become disengaged, feel that this isn’t for them.” So Alleyne and company hope to prevent this disengagement early on via a cross-disciplinary, first-year experience. “Studies have shown if you do that common first-year experience, the retention rate in the first year goes up significantly.”

Alleyne’s a huge fan of a common (or undeclared) first year, which he claims gets better retention numbers “because people have a year to figure out whether they really want to be a computer scientist, electrical engineer, physicist, etc. That first year, people tend to track into things that suit them better.”

While Illinois has undeclared engineering students, it doesn’t have a common first year; being undeclared is optional, not a requirement. So Alleyne proposes to “take the current structure, where we have departments, and institute cross-disciplinary, first-year experiences,” adding that, “We want to do the pilot to make sure that will work.”

They envision freshmen taking first-year design courses that introduce them to a number of engineering disciplines to see if this increases retention. He proposes to “start with a pilot group, have them work through a semester’s worth of design topics, and see if that cohort has higher retention numbers. I anticipate that they would, because we try and create authentic experiences—something somewhat realistic they can see in everyday life.”

In line with their overarching emphasis on sustainability, Alleyne would like to see the first-year interdisciplinary emphasis instituted college-wide. “When you’re starting something and you’re trying to make it last and be sustainable, you want to get some very key tangible wins early. If we are able to demonstrate among these key departments that we can actually get integrated design experience, then we can start to institute and decide if we want to broaden this, make this a policy across the college because we’ve seen the numbers and have the data to make our decisions.”

So plans are underway to get some projects in place, do some curriculum design, then hopefully pilot a course in fall ’16 with around 5% of the engineering freshman class. “That’s a healthy number to start with. That’s a strong evidence to try and make something more institutionalized.”

According to Alleyne, making the first-year initiative sustainable, or institutionalized, is “the critical part of the middle piece…POETs is built to stick around. Going to take time to make sure to get it right. Because we’re trying to build this thing to last, we don’t feel that we have to get results to write an article or a paper in year two or year three. The goal is bigger than that.”

So they intend to take their time and do it right. “We want to run that [first-year experience], get the learning assistants’ feeding back, get the intergenerational thing built up. Then the people that did it their first year, we would want to give them a similar type of experience their last year to bookend that.”

Getting rich data regarding the effectiveness of the first-year program will be crucial. “If it works,” acknowledges Alleyne, “we’re asking the College of Engineering, one of the top five engineering programs, to change how they do things. They’ve worked pretty well for a long time, so if we’re not pretty thorough in how we gather the data to make that suggestion, there’s far too much risk to change what works very well.”

Contributing to the first-year program’s sustainability would be another key emphasis of POETS—intergenerational experiences. For instance, Alleyne envisions older students “looping back” to impact the freshmen. “First year experience is bolstered by people that do well in the first year experience and really like it. When they go to their second and third year they loop back and interact with the first-year students as learning assistants.”

To further contribute to undergraduate retention and to engage underrepresented students, POETS intends to implement a Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU), which would go beyond traditional activities, exposing participants to not only research and reporting results via posters, but how to write graduate research fellowship applications. This summer's REU would probably start small, around 4 or 5 students in each of POETS’ institutions.

Another undergraduate research program being considered is a continuing REU program. They envision that it would eventually involve 20–25 campus undergrads who’d be housed in the POETS office and involved in an ongoing, year-long REU experience. By alternately engaging these students in both research and working with industry, students would hopefully learn some additional tools and eventually end up with a good toolset.

T-Shaped Post-Baccalaureate Students

POETS PI Andrew Alleyne (center), with Pramod Khargonekar, NSF Assistant Director for Engineering and NSF Director (left), and France Cordova (right) during POETS' fall 2015 kickoff event.

POETS’ third thrust is shaping post-Baccalaureate or graduate students who are comfortable in an interdisciplinary environment. “Our goal there would be the T-shaped engineers that people talk about. They have depth in one area. You go to grad school to gain some depth and become an expert in a particular area,” Alleyne acknowledges. But in addition to depth, they would also like their students to have breadth: “to become experts, but also be relatively broader than the average engineer. They will have to understand that coming in. It will take a while to build that culture, but this will be the culture we are trying to build.”

One strategy to encourage this seems fairly simple on the surface (although it might involve some infrastructure changes): “We’re going to go with an open office type of plan, which we don’t have here on campus very much. Open office—you don’t have walls or dividers; it fosters collaboration. You get to learn about what other people are doing by osmosis. You have to be willing to work in that environment to succeed.”

Alleyne indicates that over time, students’ willingness (or lack thereof) to work in that environment might cause some self-selection. “The folks that want to do their own thing may not choose to come here. But I think there is a large enough section that want to be a part of something bigger than just what they’re doing.”

What Alleyne is proposing actually goes beyond changing the infrastructure; he calls it a culture shift. “There’s a big difference between being multidisciplinary through email versus you living and breathing in the same space with those individuals every day. You can tell the difference. The way we’re doing it is a culture shift. Right now, each grad student is in their own office...It's different than if we don’t have walls.”

“If successful,” he adds, “it will change the way we do things here on campus.”

Alleyne explains that their research revealed that what they hope to implement would take a certain kind of people: “a significant demographic shift in terms of age demographics about people that are more comfortable working in an open environment. Younger people, yes. Also certain cultures are not as receptive.”

So POETS has come up with several strategies “to generate that agile, interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary type of person—a person that’s comfortable in many different environments.” Alleyne says, “Training people to work in more open collaborative types of environments is part of the education.” They also hope to get students off-campus experiences with international partners, plus expose them to industry. According to Muskin, breaking down silos is “Not just interdisciplinary…So two big walls to break down. One is the departmental walls, but also the walls between academia and industry.”

Intergenerational Experiences

Regarding POETS’ intergenerational thrust, Alleyene offers a pithy proverb that epitomizes his philosophy: “The sales department in a company isn’t the whole company, but the whole company better darn well be the sales department.”

In other words, he expects sold-out engineers produced by his system to “sell” it to the younger ones. “The post baccalaureate will loop back and interact with first years and seniors in undergrad,” he envisions. “Some will loop back with K-12 to try and change the idea of what STEM means. People have a stereotype of people going into STEM. When you start bringing back advanced degrees they show that there are many types of people that can like this and be successful.”

And he intends that they become perpetual ambassadors of the program: “The hope is that it gives them a broader and richer experience. When they launch their own careers, they understand that they’re part of an organization. They understand that to be successful, it’s not just what they do, but what they do in a context of a larger team. Part of that learning process is how to communicate efficiently and effectively to people of different backgrounds.”

Reaching Out to Underrepresented Minorities

Another goal of POETS is to increase the number of underrepresented minorities that enter the STEM pipeline. A number of POETS’ programs, such as the REU and the Young Scholars programs, will be specifically targeting underrepresented minorities, as well as women.

According to Muskin, one reason is to increase the number of engineers. “It’s important to broaden the pipeline,” he acknowledges. “We want to make sure that we bring in underrepresented minorities. That’s a large focus on a lot of these efforts, because we really need to expand the number of people engaged in engineering. Unless we start engaging the underrepresented populations, we’re never going to have enough engineers.”

He also acknowledges that a diversity of perspectives is needed to solve society’s problems:

“Bringing in more people, you get a lot more solutions, a lot more creativity. People see things differently, and that’s so important. If we’re going solve the world's problems, we have to have people solving them from different perspectives. We have to have different ideas coming in, to get creative. You don’t get that unless you really expand who’s involved in engineering.”

Sustainability

One key emphasis for POETS, a 5-year grant with a possibility of renewing for five more years, is sustainability. “We’re putting the time and effort in so it’s built to last," says Alleyne. "Many of the decisions we’re making and have made were with sustainability in mind. Does that mean we will suffer on some other metrics? Yes, but that’s a strategic decision we’ve made consciously.”

Alleyne believes the interdisciplinary, adaptable graduate students POETS produces will ensure its sustainability: “We want our T-shaped engineers to be several years ahead of their competitors and peers when they come out. Sustainability. If we are able to generate students like that, people will want to see this continue. It will be easy to recruit partners because they will benefit from this.”

Does Alleyne want all of the students POETS impacts to end up with PhDs in his field, or at least end up in STEM? Not necessarily. He calls the STEM pipeline a “leaky bucket, leaky pipeline. There’s only so much you can do.”

But he does have specific goals for the young people his program works with. “You want to get as many people here that are capable of making that next step, but if there are people that decide to get off the STEM pipeline after 12th grade, at least they understand why STEM is important. Grad students, at least when they come out, they are able to work in interdisciplinary teams. They’re benefiting from this multidisciplinary type of working across different areas and cultures and teamwork. PhD, they have the T shape to them. It’s ambitious.”

Author/Photographer: Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: Funded, Graduate Education Reform, K-12 Outreach, POETS, RET, STEM Pipeline, Undergraduate Education Reform, Underserved Students/Minorities in STEM, 2016

For additional articles about POETS, see:

.jpg)