At NGS' Science & Engineering Fair 2017, Every Student Is a Winner!

March 6, 2017

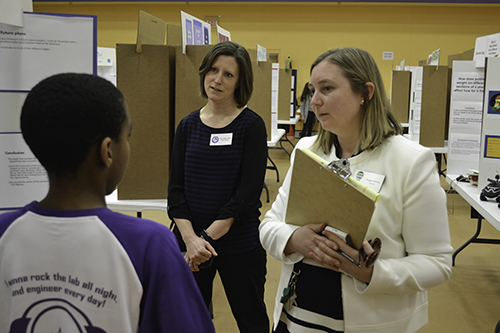

An NGS student presents her research to MCB Ph.D. student Mara Liveszey.

Friday, February 17th, 2017 wasn’t just any day at Next Generation School in Champaign; it was the day of the much-anticipated 2017 Science & Engineering Fair. And just as in previous years, it wasn’t a competition— no individual student or team won a ribbon or prize for having the best project. All the students were winners: they designed and completed a research project, learned the scientific or engineering method, and prepared a poster. Then, after working on their project for weeks, students finally got to present them to community experts, many from the University of Illinois, who provided not only positive comments about what students had done well, but ways they needed to improve, and even suggestions regarding further research they might do in the future.

Head of the School, Chris Bronowski (center), and Angela Nelson (right), director of NGS' after-school STEAM Studio program, listen as an NGS student discusses his research project.

In choosing this year’s project, the students had been encouraged to choose something that was relevant to them—something they were interested in. According to STEAM Studio director Angela Nelson, who served as one of the community experts who helped evaluate the kids’ projects, this is one thing that makes the Fair so special.

“I love seeing the range of products that these students come up with,” she acknowledges. “Their interests that show up—you might not even realize where their interests lie, and all of a sudden they’ve created this amazing project and product that they’re so proud of related to topics that they enjoy.”

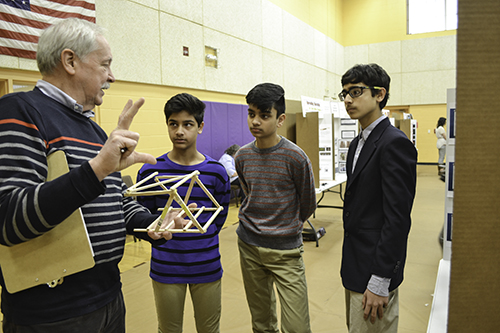

Left to right: Illinois expert Bill Rose, of the Applied Research Institute, discusses their bridge engineering project with three NGS students who participated in the EOH Bridge Challenge.

In regards to choosing their project, one thing that was different about the fair this year was that a number of the kids built bridges. Students were made aware of the opportunity to participate in a challenge sponsored by the College of Engineering at Illinois called the Engineering Open House (EOH) Bridge Challenge. So several groups of NGS students not only got to design a bridge and create a model which they presented at NGS’s Science Fair, they will also get to present it some of the thousands of visitors who will visit campus at the EOH in March.

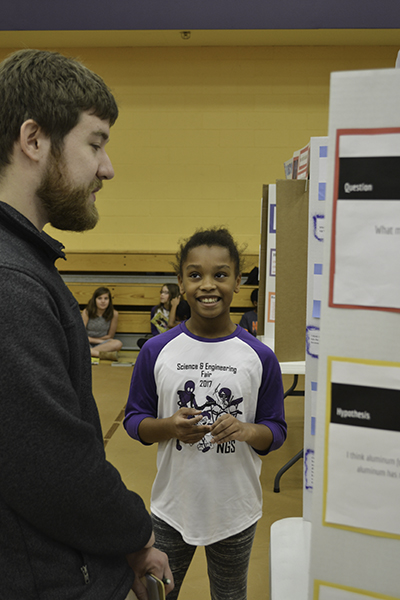

An NGS student presents her esearch project to Illinois biochemist Maxwell Baymiller (right).

According to Bronowski, the middle school science teacher, Bryant Fritz, learned about the challenge through an email and thought, “That’s so cool! Lets see if we can incorporate it!” They gave kids the option of doing it, and “A few of the kids jumped on it!” she says.

After choosing a research subject that intrigued them, students researched their subject in depth, designed their study, then conducted the research project. Of course, in addition to performing their experiments, another key aspect of the project was learning how to make a high-quality research poster. And of course, for the pièce de résistance, they got to present their project to a local expert.

Head of School Chris Bronowski stresses how important meeting with an expert is to her students: “All of the children coming in this morning, dressed up, kind of nervous, and butterflies, but excited… and to see those interactions!”

And according to Bronowski, the impact of meeting and engaging with a real-world scientist is not just for the day of the Fair…and maybe the day after. “Students talk about their expert that they presented to for years. I mean years. So it’s a really powerful, powerful thing that they’re doing for us.”

An NGS student demonstrates his research project to Illinois researcher Marty Burke (right).

To participate in the Fair, most of these faculty and graduate students put their research and other responsibilities on hold for a morning in order to interact with the next generation’s budding scientists/engineers. And while the students know it’s an “expert,” most probably don’t have any idea the important research some of these folks are doing For example, this year Illinois Chemistry professor Martin Burke, whose research to create molecules more quickly will someday lead to cures for numerous diseases, could be found at the Fair, kneeling on the floor across from a young student, discussing his or her project with them. (Many of the experts tend to bend or squat down so they’re on eye level with the young scientist-to-be whose project they’re evaluating.)

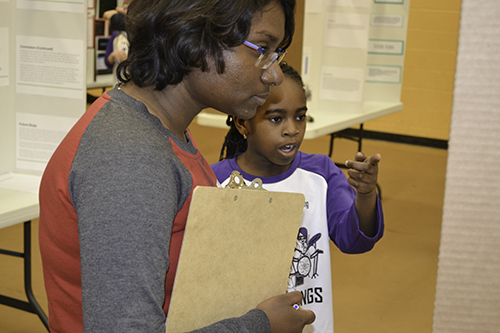

Madhura Duttagupta (left), a first year grad student in Illinois’ School of Molecular and Cellular Biology discusses an NGS student's project with her.

Another community expert was graduate student Madhura Duttagupta, who participated in the Fair as an expert for the very first time was. A first-year grad student in Illinois’ School of Molecular and Cellular Biology, her research looks at the formation and breakdown of cell cytoskeleton, specifically at the breakdown of a protein called actin.

Duttagupta recalls receiving an email saying, “This is fun; maybe you should try it!" from the MCBee outreach coordinator Mara Liveszey. So she thought, “Yea, I liked to do these kinds of things when I was in school.” She reports feeling “really out of touch, since grad school is very hectic. So we don’t get to see that fun aspect of doing science every day," she continues, "because we’re stuck in our experiments and literature. So I thought that this would be really fun.”

An Illinois graduate student in MCB listens as a student presents her research.

Duttagupta also saw it as a great way to get involved with the community. “I am kind of new here," she admits, "and I thought that going out and meeting with the kids would be a fun way of getting into and interacting with the community.”

STEAM Studio director Angela Nelson echoes the importance of the community experts: “I also love the connection with the community—that we have all of these guest experts that come in and work with the students and give them that feedback on all that hard work that they’ve done.”

An NGS student present his research to Brian San Francisco an Illinois IGB researcher.

But while the students most likely believed that presenting their research to an expert was their most important take-away from the Fair, Bronowski believes it’s the process they went through preparing for the Fair—and learning from their failures. She says that’s why they do it every year.

“Well, we do it because of what it gives our students. There’s a lot of work that goes into it, both on our end of things and on the students’ end of things, for parents. There are probably times when families probably feel like, ‘Why are we doing this?’ when it’s failed. But, through that, through those failures, through that process, they learn so much, and I think we have done a better job of helping students be ok with the process, and understanding that it’s not going to go the way that you expect all the time, and that that’s ok, and how do we move through it?”

Nor do the experts, many of whom are students themselves, who are busy doing their own research and working on their Ph.D.s, grasp just how appreciative Bronowski and her staff are of the people that volunteer their time to come in and be the community experts.

She sought to express her gratitude. “I’m sure that it is difficult for people who just come in—they talk to students, and then they leave—to understand how important their role is, and how much it means to the students, and how much it means to us to be able to provide that for our students. There’s no way to thank them enough for giving up their time to do that.”

Desaray Shepston, the new NGS primary science teacher

While the kids might have been beside themselves with anticipation, it wasn’t just the youngsters who were excited. For Desaray Shepston, a new primary science teacher who has been teaching at the school for less than a month, this was the first time that she’d ever done a primary-level education science fair sort of thing. She reported, “I’m actually looking forward to it, very much.”

Specializing in environmental studies, Shepston came to Next Gen from the University of Illinois in Springfield with a Ph.D. in environmental geography. She indicates that the primary level (kindergarten to 5th grade) had a lot of “really impressive projects that students have been very creative in coming up with the ideas for what they’re doing.”

Illinois Chemistry instructor and Chemistry Merit Director, Gretchen Adams

And considering her penchant for environmental studies, it makes sense that she recommended that visitors to the fair catch the primary C (2nd grade) class which she claimed, “has done a really interesting project on pollution and plants, so that’s doing to be a good class to look for.” She also asserted that her older students in the independent levels, Primary D, E, and F (3rd through 5th grades), “just had a lot of very creative and very challenging projects, that they’ve done very well on.”

Shepston claims that one reason the fair is of benefit to the kids is that the projects deal with real-world issues and, of course, the kids have a chance to employ the scientific method.

An NGS student explains her project to Illinois MCB Ph.D. student Kristen Farley.

An Illinois researcher and an NGS student interact while she presents her research poster.

“It gets them really thinking about what it means to be a scientist. They get to think through things that they are interested in, but, also work on the scientific method, in what would be a real-world setting. If they go on into science and engineering, they will be continuing to do this sort of process throughout their lives.”

She also says that because it’s a different way of learning compared to in a classroom setting, it can help to interest kids in STEM:

“It also, I think, engages them in the material in a way that’s different than class. They get to think about it for weeks at a time, and they take ownership of what they are doing, and so they are highly invested in it. And I think that is something that can really pique a student’s interest in science, and technology, and engineering. So I think this is a really great opportunity for students at this age.”

Bronowski, who wears two hats (Head of School and, more importantly, Mother) gained some new perspective this year regarding the Fair's impact. She shares an anecdote about her kids which captures the anticipation and excitement students are sensing…sometimes years before they actually participate!

“I think this year, especially, for me, personally, was a bit of a revelation,” she explains, “because my daughter is in 1st grade this year.”

(As an aside, when this reporter teases her about how for years, as head of the school, she’s been “dishing it out”…but now, as a parent in the throes of helping her kid prepare for the Fair, she’s on the receiving end—she laughingly agrees, admitting, “I’m on the other end of things.”)

She explains that last year she went through the process when her daughter was a kindergartener, but now, she’s in first grade.

“And what has been so cool for me to see, is how…this year, she understands it at a deeper level, and she’s already starting to think about what her project is going to be, and she’s looking forward to when she gets her own board, to present. And she’s starting to look around. She rides horses, and so, now at the barn, she’s looking around, because she’s decided she’s doing an engineering project when she does her first project. So she’s looking around for things that she can improve, and problems that she can work on. So, to see her thinking in that way, and to hear her and my son, who is in kindergarten, so now they’re talking about it a lot…to hear the conversations that they have…this is why we do it!”

Left to right: primary science teachers Ashley Kozak and Desaray Shepston; Bryant Fritz, Middle school/ junior high science teacher; Kathy Feser, primary science teacher.

On hearing that this reporter had been hearing from colleagues whose kids go to NGS—not complaints, mind you, but honest assessments—about the amount of work that’s involved in helping their kid prepare for the fair, Bronowski laughs, then acknowledges:

“No doubt about it, it’s a lot of work! But that’s ok. Sometimes there’s just a lot of work that has to go into things.”

More: 6-8 Outreach, K-6 Outreach, Next Generation School, Science Fair, 2017

For additional I-STEM articles highlighting Next Generation School's partnership with the University of Illinois, see the following:

- 2016 NGS Science & Engineering Fair Fosters Research/Presenting to Experts

- 2015 NGS Science & Engineering Fair Called the "Most Successful" Ever

- Next Generation School's Science and Engineering Fair: Every Student Is a Winner

- Next Generation School Fair: Tomorrow's Scientists & Engineers Meet Today's

- Local Teacher Uses Project Lead the Way to Prepare Next Generation of Engineers

- MechSE Gives Back to the Community

Three NGS students discuss their science fair project about whether salt impacts the growth of plants with Illinois expert Max Baymiller.

.jpg)