NanoSTRuCT Introduces BTW 3rd Graders to Nanoscience and Nanotechnology

December 9, 2014

A BTW 3rd grader participates in one of NanoSTRuCT's hands-on activities about biotechnology.

In 2014, Illinois graduate students have been sharing their expertise in nanotechnology with Booker T. Washington STEM Academy (BTW) 3rd graders as a part of a student-created/student-led outreach program called NanoSTRuCT (Nanoscale Science and Technology Resources for Community Teaching). The brain child of two Ph.D. students, Alex Cerjanic and Brittany Weida, NanoSTRuCT is partnering with BTW to do what its name suggests—teach the community (especially youngsters) about nanotechnology.

Since NanoSTRuCT has lots of bioengineers, fall 2014 outreach sessions at BTW emphasized biotechnology, and weekly visits each had a theme. For example, “Body as a Machine” looked at the body/organs as a coordinated system; then students discovered how the eye is like a camera by disassembling a digital camera to compare its components to an anatomical model of the eye. The “Blood-Pressure-Cuff" activity during the “Science of Medicine” session about how diseases are developed, diagnosed, and treated, taught students the importance of measuring blood pressure, what it means, and healthy strategies to lower blood pressure. The 3rd graders learned how scientists model organ systems and miniaturize laboratory diagnostics in the Lab/Organ-on-a-Chip lesson. The final lesson emphasized Tissue Engineering (TE): stem cells, scaffolds, breakthroughs and challenges in TE, and the Tissue-Engineered pancreas.

Bioengineering graduate student Brittany Weida, NanoSTRuCT co-founder and leader, shares a lesson about the pancreas with a group of BTW 3rd graders.

In addition, Weida says that last semester, many BTW students expressed interest in Diabetes because family members have the disease. Thus, they incorporated activities related to it in the lessons, such as one about the pancreas and another about how to measure blood sugar with a glucose meter.

Spring 2015 lessons will emphasize nanotechnology: electroplating, fabrication, copper-plated nickels, and fabricating self-assembly alginate molecules.

While the bulk of NanoSTRuCT’s volunteers are from the CMMB IGERT and M-CNTC training grant, Weida and Cerjanic have recruited students with a STEM focus across a broad range of STEM disciplines: Engineering (BioE, Mechanical, Electrical, and Chemical), Chemistry, Biochemistry, Neuroscience, and Pathobiology, plus a VetMed student and a couple in the Medical Scholars program.

So why would grad students in the throes of acquiring their Ph.D. degrees and involved in important research, such as Weida, who is working to understand pancreatic cancer, and Cerjanic, who is studying how microvasculature changes with age, take the time to work with third graders?

To “give kids a little bit of early exposure to nanotech,” says Weida, but mainly to “get them excited about STEM and the sciences in general.”

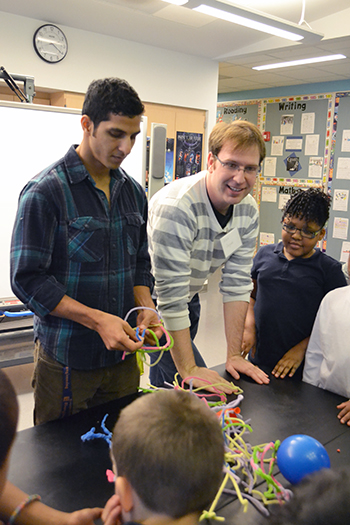

Illinois grad student Rishi Singh (left) and NanoSTRuCT co-founder and leader Alex Cerjanic (center), who is in both the MD [medical doctor] and Bioengineering programs, use a hands-on activity to teach students about nanotechnology.

Cerjanic agrees, then adds that he’d like to expose the students to scientific thinking.

“The most important thing we can do is give them a better sense about research and science and the advances going on…what that thinking looks like in terms of asking questions, making hypotheses.”

He also wants to help teachers pique kids’ curiosity and interest in science—something that he didn’t have as a youngster.

“And also just being interested and curious about things in front of them. I know when I was in school at that age, I didn’t have that sense of science. I liked it, but it’s so hard to get that sense of inquiry and investigation because teachers have so many things to do, and their resources are limited. It’d be great if we could bring some things to inspire them.

But it’s not just BTW students who benefit from the partnership; the NanoSTRuCT folks do too, such as learning how to distill their research down so the general public understands it.

“If you can explain it to a third grader, you can explain it to anyone,” says Weida. “And just having to improvise and work under pressure—those are good life skills.”

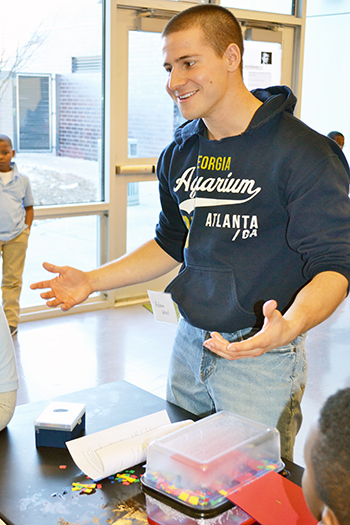

Illinois grad student Rishi Singh interacts with a BTW student during a NanoSTRuCT session.

Cerjanic also believes he and his cohorts have developed their leadership skills. He calls Ph.D. students “one of the cogs in a machine” in a lab. However, “If you go into industry,” he continues, “you’re no longer a cog in the machine; you have to lead the machine.”

“This is a great opportunity to take ownership,” he adds, “to build something up that is ours, that we can take pride in as something that students have designed, built, and led. Because these are the skills that we’re going to use if we become researchers.”

BTW third graders are eager to give input during one of the NanoSTRuCT sessions.

Cerjanic and Weida didn’t just wake up one morning thinking, “I’m going to start a new student organization dedicated to Nanoscience outreach today.” The idea was fostered through previous outreach opportunities.

Because the core of NanoSTRuCT is students from two NSF-funded programs, as a part of NSF’s broader impact mission, they had already done outreach: the Urbana’s Farmers’ Market on Saturdays, and Engineering Open House (EOH). However, rather than just meeting the public for very short periods; they wanted to do more than just give a cursory introduction to their research.

“A lot of us realized we wanted something that was more focused, a longer-term partnership,” admits Cerjanic. “We wanted something that was a longer, more extended sort of encounter with students, so that way we could actually go a little bit more in-depth about what we do.”

The idea of partnering with a specific school was planted during an after-school 4H SPIN club at Urbana’s Caanan Academy, where they developed and taught students four lessons, then, for the culminating event, brought students to campus for EOH—with a twist: normally Illinois students present to visitors. But NanoSTRuCT had Caanan students present what they had learned to the public.

However, in the fall of 2013, they had an epiphany: “All of us had so much fun doing [outreach],” admits Ceranjac, “we said, ‘Let’s see if we can make something of it!’” So they created NanoSTRuCT and, along with Dr. Irfan Ahmad, Executive Director of the Center for Nanoscale Science and Technology, who serves as the PI, and Carrie Kouadio, the Education Coordinator for CNST, applied for and received a Public Engagement grant for 2014.

NanoSTRuCT graduate student Claire McGhee shares a lesson with BTW students with one of the tablets the group purchased with the Public Engagement Grant funds.

Using grant funds, they purchased 10 tablets to provide visual aids, such as videos, during outreach; supplies for hands-on projects; and bussed the kids to EOH in 2014. They worked with BTW 3rd graders in spring and fall 2014, and hope to do additional modules again in spring 2015, culminating with EOH.

How’s the outreach been going? For one, the team has encountered the realities of working with K–12 students. For example, one day, two teachers were out sick, and the kids succumbed to the substitute teacher syndrome and had been acting out.

“We got a little bit of first-hand knowledge of that. This is part of working with students like this. You just have to be willing to kind of roll with the punches.”

But they have also experienced the rewards—celebrating with students as they grasped a concept and experiencing their exuberance. Weida shares an anecdote about a blood pressure activity:

“A lot of the activities, we try to get them to think a couple of steps ahead,” says Weida. So after taking the kids’ blood pressure with portable blood pressure monitors, they asked them, “What do you think will happen if you do 30 jumping jacks?” Once the kids had developed hypotheses, they retook their blood pressure.

So did the kids do 30 jumping jacks? And then some:

“The whole time; some of them just did it for fun,” admits Weida drolly, then sheepishly acknowledges: “that wound them up for the next class.”

To improve their program, they do self-assessment. “We have a little pow-wow after every visit,” Weida explains. “‘Did this activity work? Do you think we need more time for this?’”

Cerjanic also hopes to recruit a broader spectrum of grad students. While the program is currently interdisciplinary across STEM, he envisions an interdisciplinary element from across the university. “I think we need some education people involved; we need social sciences people involved.”

“Because none of us are trained to work with small children,” admits Weida.

Illinois grad students Anthony Fan (left) and Rishi Singh (center) do a hands-on activity with BTW 3rd graders during a NanoSTRuCT session.

Illinois grad students Anthony Fan (left) and Rishi Singh (center) do a hands-on activity with BTW 3rd graders during a NanoSTRuCT session.While NanoSTRuCT folks may not be “trained” to work with kids, their obvious passion for nanotech is contagious; during sessions this reporter attended, the kids were as engaged and excited as the mentors.

And even though Weida and Cerjanic still have a few years to go in their Ph.D. programs, they realize they’re not going to be at Illinois forever, and envision a “talent pipeline” to ensure that NanoSTRuCT continues even after they’ve moved on.

“Personally, I think we have to get a pipeline of people—to keep the interest going,” says Cerjanic. “Because it’s not my desire to see this die when I can no longer do it. So we’ve been really looking toward first year and second year students who are a little bit earlier in their program and are still ‘bright-eyed and bushy-tailed and idealistic,’ and we want to bring them in and get them involved.”

Illinois grad student Adam Wood shares his love of nanoscience with the 3rd graders.

One way they’ve been exploring to make NanoSTRuCT sustainable is to create an RSO (Registered Student Organization). Also, the two recognize that additional funding will be key. Both sing the praises of their Public Engagement grant. Cerjanic claims it has been, “so fabulous, because it’s really enabled us…none of this is possible without that kind of financial support.” So in the future, they will be looking at other mechanisms for additional funding.

Any chance either will abandon research for teaching?

Cerjanic says not. He feels he’s best at research but admits he’s learned a lot: “I think this has definitely deepened my appreciation for the work that teachers do, and it has also demonstrated that teaching is not what I am best at. It’s taught me a lot about teaching and what that commitment means.”

“But at the same time,” he continues, “I also enjoyed the opportunity to talk about the research, and to communicate it.” He believes that any teaching he does down the road will be tied to his research and educating the public.

Weida, who wants to get into industry, sees some type of outreach in her future. “I really do actually like working with children,” She says she’s taught ballet classes in the past, and tutored kids in math. “I guess no matter where I go, I’ll pursue similar opportunities.”

Both Weida and Cerjanic were quite proud of the investment NanoSTRuCT’s grad student volunteers made. During any given outreach session, around 8–12 volunteers ventured forth to work with the BTW students. For example, volunteers netted over 250 contact hours in the spring, 176 hours in the classroom at BTW from 29 different volunteers (not including EOH, which had 38 volunteer hours, including helping lead tours and chaperoning). Also, almost all volunteers made more than one classroom visit.

“They came back,” boasts Weida.

In fact, most volunteers came more than once, and a lot made more visits than that. “The commitment was really limited by how much time they had available, not necessarily by their interest,” says Cerjanic.

“I think it really just speaks to the commitment of our volunteers that they find this time, even though they have a million things to do,” adds Cerjanic, “…but they find the time to actually come and work with the students…without that, none of this would be possible.”

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Booker T. Washington, K-6 Outreach, 2014

Left to right: Two NanoSTRuCT grad students, Adam Wood and Claire McGhee, engage the BTW 3rd graders during a demonstration.

.jpg)