Kelsie Kelly Gives Back to the Community Via STEM Outreach and Mentoring

Community Health Ph.D. student, Kelsie Kelly.

March 30, 2015

Kelsie Kelly’s goal in a lot of what she does is to pay it forward.

A Ph.D. student in Community Health, Kelly has lofty career aspirations which appear to have been influenced by her own experiences. For one, she would eventually like to start a women’s clinic—no doubt influenced by the many outreach programs in which she participated growing up. Her other dream—starting a non-profit organization that mentors underrepresented students—probably came about because both mentoring and being mentored were so important early on in her life...and still are: "I have a bunch of mentors in Milwaukee whom I still talk to regularly to make sure I'm staying on track," she admits.

Kelly's goal, even in her educational choices, is to pay it forward. In fact, she hopes to eventually end up back in her home town, making a difference. Her plan is to “come back and make strides and make changes in Milwaukee.” When? “When I am ready,” she qualifies.

Kelly suspects her emphasis on mentoring—and paying it forward—was one reason why she was hired last fall to be the Brady STEM Academy program coordinator at Garden Hills School. Created by Dr. Jerrod Henderson, a Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering faculty member, the program seeks to make a difference in the lives of local African-American boys via mentoring.

Kelsie Kelly works with a Garden Hills student during the Brady STEM Academy after-school program.

“They loved my personal philosophy about working with younger generations and paying it forward and being a mentor,” says Kelly, “not just mentoring someone of my own gender or my own race, but being able to mentor a diverse group of people with an open mindset.”

Add to her great philosophy a ton of experience. She admits, “I like working with younger populations,” but has participated in outreach with all ages, ranging from K–4, middle school, to high school students, even adults and the elderly.

For example, in the Plain Talk program, she worked with parents, even grandparents who were “taking care of their kids’ kids.” The program’s main thrust was “encouraging care-givers to bring up the sex conversation in the home.” Kelly explains it was about "helping parents talk to their teenagers, because parents are not having that conversation.”

Involved in outreach and mentoring for years, Kelly’s been concerned with sexual health education and teen pregnancy since she was 12. In fact, her early forays into outreach in these areas may have influenced her to choose community health as a career.

“I’ve been doing it for so long that…it’s become a part of how I cater my research to think about things, sexual health and relationships, and how that affects healthy birth outcomes.”

Nor is she afraid to tackle the more difficult subjects young folks face: “I did a lot of work with HIV and AIDS, so I’m very equipped in those areas. I think this really helps in my being able to teach human sexuality at the university.”

When it comes to having the “sex talk,” Kelly had good role models: “My parents and my family didn’t shy away from it.” She recalls that they would say, “Ok, let’s all have this conversation now…so you can make healthy decisions.”

Another program in which Kelly has served as a mentor is Upward Bound, a college-readiness program for underrepresented students. Via the program, high school freshmen come onto campus during the summer to take classes that strengthen their understanding of core subject areas (science, math, and reading). Additionally, these students come on campus for tutoring and mentoring in after-school programs throughout the school year.

Kelsie Kelly works with a Garden Hills student during Brady STEM Academy.

Did any of the youth she mentored end up going to college? All of them did. Evidently the last holdout, who she’d been trying to talk into going away to school for a year or two, is now in college in Georgia.

Even back in high school, Kelly had embraced the students-should-go-out-of state-to-school philosophy. She admits to pushing them out of the nest and says a big part of her agenda was “to get them out of their comfort zone to go places.”

Her mantra was: “Apply everywhere. Don’t limit yourself to in-state because you want in-state tuition, but you’re investing in yourself. As long as you believe in yourself, you can go do whatever it is you want to do.”

She evidently persuaded ten close friends to go out of state. Most stayed there and finished school, but even the four who came back after one year, saying, “I can’t do it,” still ended up finishing school.

Kelly shares an anecdote about getting her best friend to try her wings: “I had to talk to her mom, her grandma, her dad, like everybody in order for her to go away to school,” she recalls.

But Kelly succeeded. Her friend ended up going to Howard, their dream university, while Kelly was down the road at Virginia State. However, her friend’s mom said, “'Okay, you’re not too far,’ even though we were across the country in Washington, D.C. and Virginia,” admits Kelly.

Glad that she went, her friend says, “I’m never coming back now.” Proud to have been the catalyst, Kelly boasts, “I got you out the nest! Because home is always there; you can come back anytime.”

Kelly explains why she is so sold on students going to out-of-state schools: "It was the best thing ever for us to get away from home…You have the opportunity to learn about yourself, and what you’re good at, and how you can give back if you’re going to come back.”

Kelly acknowledges that another motivation was to one day return and give back to her community: “I think one of the things that a lot of people were scared about when we left was, we’re not going to come back. But our end goal, we already had set in our minds: ‘When I’m done, I have to come back and give back to the place that raised me. So, how am I going to do that?'”

Another plus about going to school so far away was that it got her mom out of her comfort zone. “She was afraid of flying,” Kelly confides. “She’s afraid of heights, but she had to fly to see me.”

Another perk to being far away: it cut down on extemporaneous visits. She knew when her mom was coming: for the obligatory Homecoming and Mom’s Weekend visits; there was no showing up spontaneously.

“I’m leaving,” Kelly had announced. “You’re going to have to plan a trip to come see me; can’t just pop up on me and be like, ‘Let’s have lunch.’ That was not going to be the deal!”

However, when it came to going to grad school, Kelly changed her tune: she wanted to be closer to family. “Sometimes you just need to go and cry on your mom’s lap and be like, “I can’t do this” and you need the encouragement that you can’t necessarily just get from a phone conversation.”

So where does Kelly want to end up? She loves it out East, so she’d like her first job to be there. But then she wants to return to Wisconsin and give back to her home town—possibly involved in a program much like a 10-week Saturday science academy she went to as a child. She describes it as an Upward-Bound-type program focused on low-income kids who wanted to go to college.

During the program, she did more than learn about science; she developed perseverance. They had promised to pay the youngsters, with one caveat: participants had to attend every one of the sessions. “So having to get up early on a Saturday morning to catch the bus to a Saturday academy was like a whole lot,” she admits, then boasts, “But I did it, and I successfully completed it.”

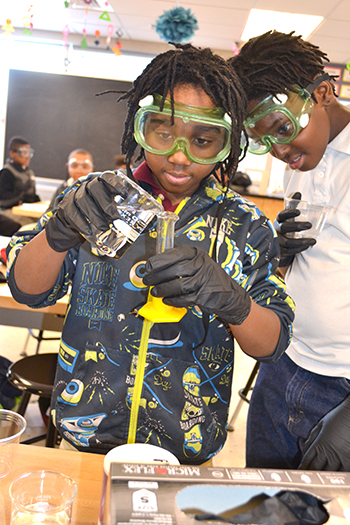

A REACT chemistry student (left) helping out during Brady STEM Academy teaches a Garden Hills student how to measure chemicals correctly during a hands-on activity.

And got paid, but even more importantly, discovered that she was good at science, and it gave her a head start which has paid dividends throughout her entire school career.

“I didn‘t even know I was good at some things that had to do with science…I found my strengths and weaknesses and what I was good at. And it helped me excel in high school in my science classes.”

It also gave her a head start in college. When taking science courses she’d taken previously in high school, Kelly reports, “I understood the basics of it because I had the class before at a different level.”

Her early experiences also familiarized her with labs and how to use microscopes. "Sometimes, it’s people’s first time even touching them in college, so I think it really, really helped.” For one, she became a classroom helper. “Which probably helped me get my A’s,” she gloats.

Was that early Saturday morning science program a turning point that set her on her career trajectory in STEM?

Somewhat, but she mostly attributes her choice of a STEM career to her mentors, who came from various STEM backgrounds. She says their input helped her settle on her area of specialization—via a rather circuitous route.

Initially, one mentor had advised, “You should just go to medical school and be a psychiatrist…just be done so you can write prescriptions.” So she had decided, “I gotta’ go be a psychologist,” but then told herself, “I don’t want to write prescriptions. I hate medicine.”

However, while getting her Master’s in public health, she worked at a hospital and had friends in medical sciences, and realized, “‘I could’ve done this.’…So I think it helped me be very versatile in how I pursue my education because I had that background.”

Kelly feels that every experience—from going to camps to working in her community—has contributed to her love of outreach and mentoring. Ironically, she didn’t initially know it was outreach.

“It was just what I enjoyed. I like working with people, so I found my niche. I’ve been doing outreach for such a long time and didn’t know it until I had to put a title on what I did.”

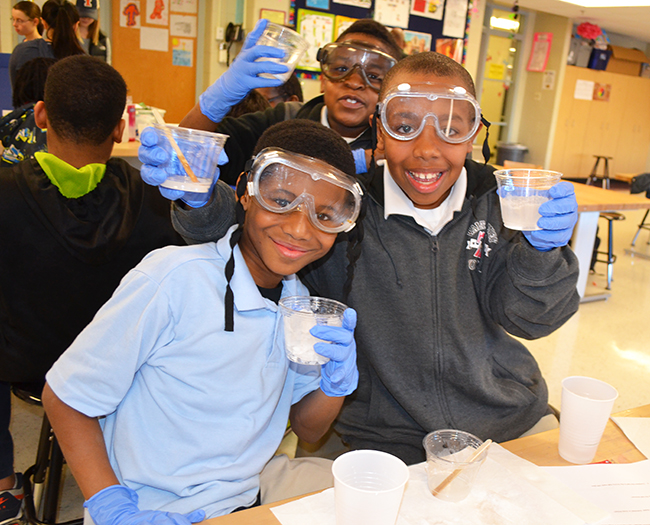

Garden Hills students doing a hands-on activity during Brady STEM Academy will soon be able to boast that they have mixed polymers.

While Kelly wouldn’t call herself an outreach expert, she does have some advice regarding helping kids learn. For one, she recommends using a variety of instructional approaches: “When it comes to STEM education, you should never do it one way. It’s multi-faceted. Because how I learn and how you learn may be different.”

Kelly thinks of her STEM education outreach philosophy as a big puzzle. “You have build on the foundation of what you’re trying to help someone learn. So it takes a piece at a time to put everything together. And if there’s one piece out of place, or missing, it’s not going to come together. So you have to make sure that you’re able to piece the puzzle together, because when you do that and use diverse technology, media, or a physical product, use people, things that we use daily, then that helps to fill in the space—where it’s just like ‘I didn’t understand how to apply that, but now I understand how these two things work together.’ So I feel like it’s a puzzle that we just keep building on.”

While it may seem a bit incongruous for a STEM program, she also emphasizes reading aloud. “Reading is fundamental,” she preaches. “It’s something I was instilled with at reading camps.” She goes on to explain that boys often, "don’t feel comfortable reading out loud.” But she soon has the boys vying for the privilege, which, unbeknownst to them, improves their reading skills. “Boys love to be competitive,” she admits. “It’s just how we ingrain them.”

Kelly’s gauge for whether a lesson was effective is whether the kids want to teach somebody else what they learned: “It’s exciting when the boys come back to the program and are like, ‘I taught my sister how to do this,’ or ‘I taught my brother how to do this.’”

She reports that they’re also proud when they can bragg, “‘Oh, we did this…” when they’re about to begin something in school that they already know how to do because they’ve done it already in STEM academy. “So they become the helper in class, versus being class comedian.”

Kelly indicates that her current outreach, Brady STEM Academy, is doing a lot of things right. For one, they’re engaging kids at a young age.

“Research has shown, the earlier the better as well, so having it at fourth or fifth grade for boys is just good because of those memories that they build.”

Kelsie Kelly interacts with a parent during Brady STEM Academy at Garden Hills School.

For another, they’re including parents, who are are excited about the program: “One of the days I missed, the mom was like, “You weren’t there; he said he was looking for you.”

She finds it rewarding when “the parents trust you with their kids because you’re helping them move forward and do something that they are not able to do because of other responsibilities."

The kids find bonding with their parents exciting too: “Having the parent there the whole time, learning and getting their hands dirty as well...I saw the father-son excitement in being competitive with each other and creating memories.”

Another thing Brady STEM Academy is doing right is “putting culture and science together.” She says that while the program is STEM based, it’s also culturally relevant. Each week they emphasize an African-American the students can relate to. “I think that’s what’s new, too, in STEM education; it’s mixing culture with science.”

For parents who would like to see their kids end up in STEM careers, or at least going to college, Kelly has a word of advice: get your kids into STEM programs.

“Don’t be afraid to put your child into those programs because although they may feel like it’s boring at the start of it, they make lifelong friends. It’s a learning opportunity and it’s a network for them to begin this early. So even if they stay in STEM or not, it’s a chance for them to learn and to make their learning capacity enhanced because of the skillset that they build in the opportunities offered to them.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Community Health, Student Spotlight, Underserved Minorities, Women in STEM, 2015

Three Garden Hills students proudly display the congealed polymers they made.

.jpg)