I-STEM Evaluators Serve as “Critical Friends” for STEM Education Programs

I-STEM evaluators Emily Gates and Sarai Coba check out data during an evaluation of I-STEM affiliate Gretchen Adams' Instructional Strategies workshop.

June 4, 2015

A trait most human beings share is that we love to receive praise about something we’re doing right, but sometimes take umbrage when we receive even constructive criticism. And folks involved with STEM education programs are no different. But when it comes to the evaluation of these programs, I-STEM evaluators work hard at being objective, describing themselves as “critical friends.” While they are pleased to inform those involved in the programs about the things they’re doing right—similar to the proverb that begins, “Better are the wounds of a friend”—they’re also willing to tell them about things that need improvement and how they could do that.

I-STEM evaluators Ayesha Tillman and Marlon Mitchell at an evaluation of a Family Day Event of the REEEC Title VI Center's program at the Savoy Head Start.

According to I-STEM evaluator Ayesha Tillman, “The purpose of evaluation is to judge the quality of a program, whether that be a STEM program, an arts program, any type of program.” I-STEM, however, evaluates mostly STEM education programs. “It’s such a hot area,” Tillman adds.

STEM education—and its evaluation—is indeed a hot topic nationally. In fact, I-STEM itself was created in response to a national mandate to divert more youngsters into the STEM pipeline: part of I-STEM’s vision is to prepare “a highly able citizenry and diverse STEM workforce to tackle pressing global challenges.” And closely related to the need for a highly able STEM workforce is the need to prepare them well—thus, the increased emphasis on the evaluation of STEM education programs.

“I think we’re at a point in United States education system where we’re trying to increase the access and quality to STEM education,” explains I-STEM Director Lizanne DeStefano. "We’d like more students to be interested in science, technology, engineering, and math, and when they’re interested, we want them to have a better experience. So I think evaluation is important for telling us, ‘Are these programs working?’”

DeStefano indicates that the second aspect of I-STEM’s evaluation approach, related to increasing the diversity of the STEM workforce, should answer the question, “Are these programs working for whom?”: “Know that there are some gender gaps in STEM education,” she continues, “that women tend to have less interest in STEM. We also know that there are many underrepresented minority groups in STEM. I think, in particular, we’re interested in understanding how these special subgroups are perceiving education, and what we can do to make STEM more interesting and engaging for them.”

I-STEM evaluator Gabriela Garcia (right) hands an evaluation form to a student enrolled in a Digital Forensics pilot course, which is part a multi-disciplinary curriculum being created by the Program in Digital Forensics, which I-STEM evaluates.

Here’s another reason STEM Education evaluation is such a hot topic: “There’s a lot of money being thrown into STEM,” says Tillman. For example, in light of the national mandate to increase the STEM workforce, a great deal of federal funding is being allocated to STEM areas; to ensure that funders, such as the National Science Foundation, who are liberally doling out taxpayer dollars are getting the biggest “bang for their buck,” they require evaluations.

While STEM educators obviously want to make funders happy to ensure future funding, most are passionate about their subject matter, extremely conscientious, and want to do a good job.

According to Tillman, evaluation “helps you know, ‘Are you doing what you think you’re supposed to be doing?’ It helps you answer the question, ‘Is this program working? Is it not working?’”

I-STEM evaluator, Jung Sung, experiences the Blue Waters supercomputer up close during a tour of the university's Petascale Facility. Sung evaluates the Blue Waters community outreach programs.

Tillman explains that to systematically judge the quality of a program, I-STEM evaluators ask questions focused on four main areas: implementation, effectiveness, impact, and sustainability. Tillman elaborates on each:

- Implementation: “Is the program being implemented in the way that it is supposed to be? Is the program following what they said they were going to do in the grant funding or the program theory or the program’s planning?”

- Effectiveness: “Is the program effective? Is it working? What’s going well? What’s not going well? How can we improve some of the things that aren’t going as well?”

- Impact: “What is the impact of this program? What are some outcomes? What are some short-term outcomes, long-term outcomes associated with this program?”

- Sustainability: “Are pieces or components of the program being institutionalized? I think that’s really important, especially for funded programs,” she adds. “What’s going to happen with this program when the money goes away?”

Tillman calls the first two questions formative, which she describes as “to give feedback along the way so changes can be made,” while the last two are summative: “What overall happened at the end,” she explains, then adds: “At I-STEM we are strong in both areas.”

“But, one of the great things about formative evaluation,” she continues, “especially for these multi-year programs, is that when they are being implemented the first year, it’s never going to be perfect, but you have a chance to get it better the next time and the next time.”

Values-Engaged, Educative Approach

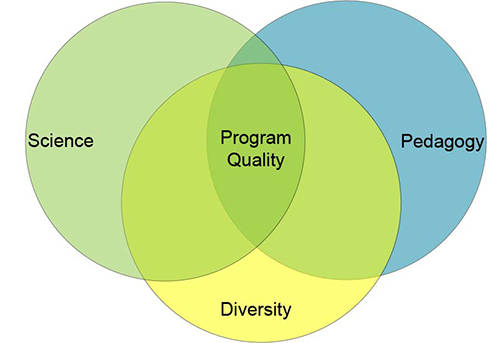

What makes I-STEM’s evaluation philosophy unique is its emphasis of the Values-Engaged, Educative Approach (see the figure to the right), which I-STEM director Lizanne DeStefano and Jennifer Greene co-authored. Of the approach’s two components, the first engages with values.

“Every program has intrinsic values,” says Tillman. “These are derived from the types of things the PI’s, program managers, and evaluators think are important. So one thing we always try to look at when we’re judging the quality of the program is ‘Does the program have high-quality science content’? ‘Does the program have high-quality pedagogy’? and ‘Is the program attuned to issues of equity and diversity’?

I-STEM Director, Lizanne DeStefano

DeStefano further develops the first dimension: “As a research-run university, and a university that excels in science and engineering, we hope that the content we put in our STEM education program is cutting edge and represents the best thinking.” Regarding pedagogy, she adds, “We’re trying to make sure that the way we deliver the content and the way we engage students in class is highly effective.” DeStefano cites some questions an evaluation might ask regarding the third dimension—diversity: “‘Are all groups in the class benefitting from this instruction?’ and ‘How are underrepresented groups benefitting from the class?’ So by looking at cutting-edge science content, effective pedagogy, and diversity, we think that we’re getting a pretty well-rounded, nuanced view of the programs.”

What’s also unique about I-STEM is that many of its evaluators come from under-served populations themselves, which sometimes gives them a slight edge when performing culturally responsive evaluations.

For example, when I-STEM evaluator Lorna Rivera was asked whether the fact that she is both Latina and a woman has had an impact when performing culturally responsive evaluations, she responds, “I would say it makes a huge impact.” She indicates that being in the age group of the target population of many of these evaluations has been helpful as well.

For instance, many programs Rivera evaluates have outreach components that target underrepresented minority students (URMs): “Many times during meetings or when we’re presenting data,” she says, “I’m able to shed additional light on the figures that we’re presenting that you wouldn’t necessarily get if you didn’t have someone from that community discussing them.”

I-STEM evaluator Lorna Rivera

Rivera shares an anecdote about a series of focus groups with URMs (a large percentage of whom were Hispanic), where her ethnicity was extremely beneficial.

“Since I came from that community, I was able to discuss my personal experience with them, and they opened up to me…In a crazy way!” she exclaims.

“They would say, ‘Well, you know how it is,’” she continues, “and I did know! Whereas, if you’re not coming from that community, the students just kind of feel like there’s no point in talking, because you don’t understand.”

So what happens when the values of the evaluator and the values of the PI or the program manager at NSF or another funder aren’t the same?

“I think that we’re very lucky,” admits DeStefano, “because this framework was developed with National Science Foundation support. It is very in line with NSF’s values, and if you read the program announcements from NSF, they are interested in those three domains as well. I think one of the reasons I-STEM is very popular and people want us with them is because we do reflect NSF’s values, and NSF is a very big funder on this campus.” In fact, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign receives the most NSF funding of any university in the U.S.

She acknowledges that sometimes program staff or PIs may not share all of the values noted above, but most eventually come to value those as well.

“But we do not yield on those,” acknowledges DeStefano. “We continue to look at those three lenses; we continue to give them information, and I would say that, in some cases, that does seem to shift their focus to one of those areas that they may not have had much interest in, like pedagogy, ‘Are we using the most effective pedagogy?’ or diversity, ‘Are we getting the most diverse group possible?’ or ‘Do we have ways of attracting underrepresented students in our programs?’”

Regarding the second piece of the Values-Engaged, Educative Approach—being educative, DeStefano reports that it is “not just accepting people where they are, but trying to bring along their program understanding and to help them see how these three domains are a useful way of thinking about their program.”

I-STEM evaluators never know where an evaluation might take them. Above, Sallie Greenberg and Lizanne DeStefano suit up to enter a coal mine as part of an evaluation conducted for the State of Illinois' Department of Commerce and Economic Opportunity.

Adds Tillman, “We really want to teach our stakeholders or our clients about their program, because sometimes you have an idea in your mind, but once the program is being implemented, it may take a completely different shape, a completely different form…we also try to help our stakeholders [that’s an evaluation word]—our clients—think evaluatively. We want them to be able to come up with metrics and to be able to think, ‘Well, if I give this workshop, what are some reasonable outcomes that I’m hoping to have emerge?’ Working with them...we can see over the years how it improves.”

DeStefano indicates that part of an evaluator’s role is to help stakeholders understand how evaluation is valuable to their program:

“I think sometimes people don’t see the utility of having an evaluation,” she comments. “It costs money, and they maybe would rather use part of their budget to pay for supplies or another research assistant or something. I think they sometimes question the value added. Are they really going to learn anything from this? Is it worth paying for this evaluation? I think that’s a challenge to evaluators. You have to make what you provide worth the cost, and I think for many of the programs that we work with, people end up agreeing that this was actually a good investment.”

I-STEM evaluator Lorna Rivera (left) and her husband prepare to fill out evaluation forms during a preview of the CADENS project's Solar Superstorms documentary at Parkland Planetarium.

Regarding I-STEM’s evaluations being worth the money, Rivera agrees with DeStefano: “The proof is in the pudding,” she claims. She explains that in one very large, multi-site evaluation, the I-STEM team was originally evaluating only one small part. Then their work got noticed, and gradually has expanded. For next year, they have been asked to take on the evaluation of the entire $121 million project. “You prove your worth,” she says, then adds, “When you care about what you’re doing, it’s hard not to do a good job.”

Also key to a good evaluation is objectivity. Rivera alludes to projects where, in order to save money, the project coordinator evaluates the program. According to Rivera, this evaluation will most likely not be extremely helpful, because the coordinator is seeing their program through rose-colored glasses: “I think it’s also bad when a program manager is the only one evaluating that program, because, naturally, they’re biased,” she says.

I-STEM evaluator Christine Shenouda hands out surveys at a showing of "Solar Superstorms," a visualization created as part of the CADENS project.

Rivera goes on to describe how an objective, external evaluation is beneficial to the high-stakes program she evaluates: “You have this external member who is doing their best to objectively look at the program and offer advice to ensure that it’s successful and sustainable.”

She goes on to explain challenges large, multi-site programs with large investments face: “They’re constantly pushed to be innovative and implement new novel techniques, ideas, programs, whatever, and they’re expected to have fantastic outcomes, because it’s taxpayer dollars. And they’re expected to do this in a year.”

She says it’s almost impossible for them to do that without somebody “taking a step back and truly evaluating what’s happening.” She says their tendency is: “You just keep plowing through and worrying about meeting deadlines and implementing activities, then you’re not going to have the time to sit back and look at things objectively.” So that’s the I-STEM evaluators’ role: to take a step back and look at the program objectively.

But a good evaluation involves more than just objectivity. DeStefano adds that once projects see the data, they begin to understand the benefits of evaluation: “I would say that they may not understand in the beginning why it’s a good thing to do,” DeStefano says, “but I think when they see some of the information we produce and understand the value of having a third party, someone who really understands how to do interviews, understands how to run a focus group, understands how to do a survey, some of the aspects of social science research that we use, I think that they see a benefit from it.”

I-STEM evaluator Sarai Coba chats with undergrads presenting at the 2015 Undergraduate Research Symposium as part of I-STEM's evaluation of TOPPRS' STRONG Kids program.

One PI who sees the benefit of I-STEM's evaluation is Professor Barbara Fiese, Director of Illinois' Family Resiliency Center: "We find the ISTEM team’s evaluation of our TOPPR’s program invaluable as we develop a new flipped classroom curriculum on obesity prevention. This transdisciplinary class is being developed as a multi-site project in collaboration with Purdue University and University of California, Fresno. Being able to rely on the I-STEM team to integrate classroom evaluations across these diverse sites has been invaluable as we plan for national dissemination."

But it’s not just the projects who benefit from I-STEM’s expertise. Lorna Rivera calls I-STEM a “Professional Learning Community.” While many of the evaluation team are Ph.D. students and have studied evaluation, Rivera didn't. However, when she first started working at I-STEM, several students took her under their wing: “I got to know the graduate students really well, and because they are studying this—that’s what they’re here for—they know how to help other people get started, because that’s what they do all the time.”

Left to right: I-STEM evaluators Ayesha Tillman, Dominic Combs, and Marlon Mitchel chat during an evaluation of a family appreciation event held in May at the Savoy Head Start Center. Families who attended had participated in one of the REEC Title VI Center's outreach programs which I-STEM is evaluating..

And students are constantly vying for the chance to be a part of I-STEM and be mentored by Lizanne DeStefano. A world-renown evaluator, she believes that, in addition to taking courses, the best way students learn about evaluation is via hands-on, in-the-trenches experience.

“There’s something unique about having students in the mix,” Rivera continues, “and giving them autonomy, and giving them ownership of projects, and watching them grow, and also growing with them. Yes, they’re at I-STEM, but they’re also studying, so you can take advantage of what they study; they love to share it with you—if you’re willing.”

Sergio Contreras, one of I-STEM's data specialists who is working on the XSEDE project, poses by one of Blue Waters's many cores.

Rivera learned first-hand about DeStefano’s mentoring approach, and how she’s constantly teaching. She shares an anecdote about the day she interviewed for the job at I-STEM. After the interview was done, DeStefano invited her to come back and help with a focus group. “She’s just comfortable, and wants to bring you into the process…she just wants to teach you something…So I think that’s pretty amazing about her.”

Rivera indicates that she did come back, was promptly thrown into the water in the deep end, but quickly learned how to swim. She helped DeStefano do a focus group with several retired professionals in the community. “At the end of the focus group,” continues Rivera, “it’s customary to ask the participants if they have any questions. So they raised their hands and they said, ‘Did she get the job?’ That was the big question.”

What did DeStefano say?

“She said, ‘Yes!’” replies Rivera.

Summing up her time at I-STEM thus far, Rivera says: "It's a lot of fun. I-STEM is a great place to learn and grow, whether or not you’re an evaluator. And if you’re a program manager, our mission is to educate others, so you will be educated.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: I-STEM Initiatives, 2015

Some of the I-STEM team members (Clockwise from the left): Betsy Innes, Ayesha Tillman, Lizanne DeStefano, Luisa Rosu, Christine Shenouda, Vijetha Vijayendran, Carie Arteaga, Gabriela Garcia, Jung Sung, and Lorna Rivera.

.jpg)