iRISE Course Prepares Engineers for Community Outreach

Allante Whitmore Stanley presents her Water Filtration project to teachers during the PIFSE workshop.

July 2, 2013

Illinois graduate students who are interested in sharing their love of engineering with youngsters now have a new course at their disposal—ECE 598 EO: Community Outreach for Engineering Researchers—through which they can learn the ins and outs of outreach. Developed by iRISE (Illinois Researchers in Partnership with K–12 Science Educators), the course trains graduate students how to develop design projects then teach them to local middle school students, with the goal of creating classroom-ready teacher materials.

Of the 15 grad students who took the iRISE Engineering Design course in its debut in spring 2013, 13 were engineering students, whose fields ranged from electrical, civil, material, biological, and environmental engineering. Two non-engineers also took the course: a biochemist and an entomologist, whose research is in biomimicry. While an entomologist taking an engineering course might seem surprising, according to Sharlene Denos, the iRISE Project Coordinator and K–12 Education Coordinator for the Center for the Physics of Living Cells, biomimicry, a new science that studies nature's models and then uses these designs and processes to solve human problems, is the latest thing in cross-disciplinary collaboration. In this case, the biomimicry involves roboticists teaming up with entomologists to model robots after insects in order to build better robots.

Edison middle schoolers present the knee replacement project they made during iRISE students' visit to their classroom.

After developing the lessons, the iRISE students taught their lessons to AVID (Advancement Via Individual Determination) students at Franklin and Edison middle schools; after a test run to find out what worked well and what didn't, they then revised their lessons, then retaught them. After another round of revisions, the final lesson plans are being disseminated via teacher workshops, such as the PIFSE workshop, or the upcoming iRISE teacher workshop, Engineering a Better World, on July 25th. Teachers will also be able to download them through iRISE's website.

Even though most of the graduate students who took the course will seek jobs in industry, they're still interested in community outreach. "Most of them want to give back," says Denos. "They feel like their lives might have been different if they had been exposed to engineering earlier." Denos reports that at least one student said, "'I did participate in programs like this, and it made such a big difference for me, and I want to give back.'"

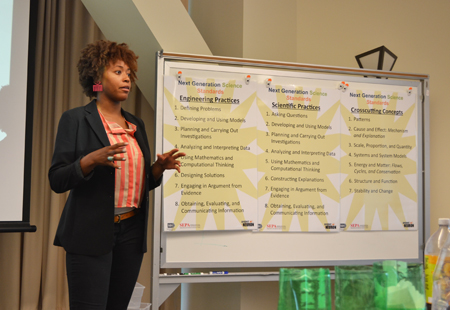

Allante Whitmore explains how the water filtration lesson she created aligns with the Next Generation Science Standards during the PIFSE workshop.

This is the case for Allante Whitmore Stanley, an iRISE grad student in Agricultural and Biological Engineering who created a "Water Filtration" project. She definitely wants to give back. From Detroit, Michigan, Whitmore Stanley attributes her current career in STEM to participating in free or reduced programs as an urban youth. "I'm actually a product of a lot of different STEM outreach programs. I was in math camp, science camp, engineering camp from middle school through high school." Based on the influence of these outreach activities in her own life, her future plans include involvement in similar types of outreach so she can pay it forward:

"That is important to me because I know that I wouldn't be here if it wasn't for those programs and those people who instilled this ability in me. So, really, I'm pursuing my advanced degrees for the sake of being able to have the freedom and the funds to have my own after-school program or Saturday morning program to educate minorities and young women about STEM."

Her goal is some combination of research and outreach: "That's my hope. That's what I really want to do. That's my true passion. But the engineering is what I'm good at, to get to what I really want to do, which is outreach."

Middle school student works on his engineering design for a knee replacement.

Whitmore Stanley's target group is middle schoolers. "I prefer middle school students" she says, "because they're a little bit more open. And research has shown that once students reach high school, they've decided whether or not they want to go into a STEM-related field. Really, the target age is from 4th–7th grade. So I think that it'd be really important to get to that group and to educate them about STEM just to let them know that it's a possibility."

While the iRISE students might want to do outreach, they don't necessarily want to be teachers, and weren't thrilled with the formal lesson plans Denos made them come up with since they would be presenting their lessons in a school setting. "There is a little bit of push back from the grad students," acknowledges Denos, "saying, 'Why are you trying to make us like teachers? We don't want to be teachers. We just want to do outreach.'"

Despite this, Whitmore Stanley felt the class better equipped her to do outreach, something that had never been addressed in her engineering education. "It just really gave me the tools that I needed…Because as an engineer, you don't really learn how to do outreach. How do you teach a group of students? How do you reach the students that might not understand, and how do you increase their understanding?...I knew what I wanted to educate them about, but actually making sure it's impactful to the student was a tool that I did not have prior to the class. That was something that was definitely instilled in me, and I feel confident moving forward."

iRISE grad students Irisbel Sanchez and Vishal Bakshi assist Edison middle schoolers with their design project, which was to design a knee replacement.

Another student, Irisbel Sanchez, took the course because, never having been a T.A., she wanted to get some teaching experience. Although her career plans are research in industry, she hopes to be involved in her company's outreach activities, and possibly to teach some time in the future. Because her teaching partner, Vishal Bakshi, is in civil engineering, and because she is in biochemistry, they decided on a bioengineering project: designing a knee replacement. Were there any future engineers among the group of students they taught? Maybe. "There were kids that got a lot, because they were really into it, so they learned many things about engineering, and they were involoved in the whole process of designing a knee replacement. But there were other students that were not that into it. I think this was the hard part for me, because I wanted them all to be involved. But the students got the general picture of what it is to be an engineer, and some of them decided, 'Yea, I like this, so I'm gonna' get into it. I wanna' do this project,' and other students decided that they didn't like it."

According to Denos, part of the iRISE students' purpose in doing the community outreach is to steer kids to STEM: "The graduate students really like what they do, and I think they want to show kids that it's fun; it's a promising area for the future in terms of career opportunities, and you can make a decent living, and you can change the world, and I think they are trying to show them that."

While Whitmore Stanley's goal is not to steer every youngster into STEM, she hopes to let them know that it's a career option. "Not that I want every single person that I meet to become an engineer or mathematician—but just the fact that you're more than capable of doing this. Because a lot of students lack the confidence—that belief that they can even excel in those particular subjects, which seem to be the harder subjects in school."

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Champaign-Urbana Community, Graduate Education Reform, iRISE, Underserved Minorities, 2013

Two Edison Middle School girls work together to create a model of their knee replacement design.

.jpg)