ISE’s Molly Goldstein: Passionate About Teaching Engineering Students Design

September 30, 2020

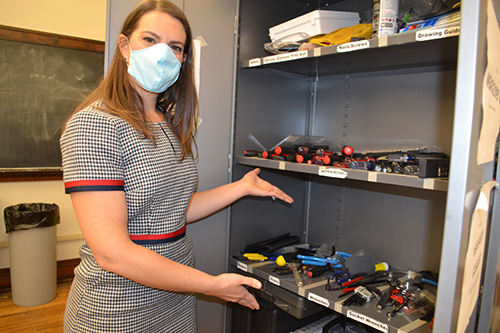

ISE Teaching Assistant Professor Molly Goldstein.

“My role is…being coach and helping students see what some of their strengths are, and what may be perceived as a weakness, and play into those so that they can play into their strengths. – Molly Hathaway Goldstein

Like many of today’s young people, when she was growing up, Molly Goldstein wanted to make a difference. Currently an Industrial and Enterprise Systems Engineering (ISE) Teaching Assistant Professor and Director of the Product Design Lab, Goldstein acknowledges, “I knew that I wanted to be in a career where I was making an impact and helping people. From my first immunization through high school, I thought that was through being a medical doctor.” While she didn’t end up being a doctor, along her journey, she discovered her real passion, and is now poised to make a difference in the lives of numerous engineering students, to help make them the best engineers possible, so they can achieve their own dreams.

Goldstein exhibits the variety of tools available for students in the Product Design Lab.

As a child, Goldstein wanted to become a medical doctor. But then she discovered Biomedical Engineering. “I love math,” she says, and at the time, she told herself, “Maybe this is an interesting way to combine my strengths and be helping people.” However, during an Illinois camp before her senior year of high school, she discovered that General Engineering (GE) would allow her to focus on bioengineering, with a heavy design focus. (Plus, back in 2000 when she started school here at Illinois, GE was in the College of Engineering, however Bioengineering was not, but was a part of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.)

So she got her Bachelor's in General Engineering, which is now ISE. “Because that is a major where you really focus on a specialty, and within that major, I focused on Biomedical Engineering. So it allowed me to have that focus, but have a really strong design background.”

Continuing on at Illinois for her Master’s, also in Systems Engineering, her dream job at that point was engineering consulting, “So I could see as many different industries and as many different projects as possible,” she reports, which she did for six years, absolutely loving it. “I felt that having been an engineering student at Illinois, I was really prepared,” she recalls. Regarding the brand new problems one always faces as an engineer, she shares the caveat “Nothing is really what you learn in school,” she continues: “But you learn how to think, and I think that I learned so many of those really valuable skills during my time at Illinois.”

Goldstein by a CAD drawing one of her students made.

But, after six years in industry, Goldstein took a U-turn career-wise, and went back to school for a PhD in Engineering Education. She shares how this change in her career trajectory occurred. According to Goldstein, the seed of her love affair with engineering education was actually sown when she was an undergrad, during a freshman year 100-level engineering design course. Then the seed was watered when, seeking her Master’s, she served as a graduate teaching assistant for that same course. “I fell in love with it,” she admits. “I love seeing how people learn and understanding that as much more of a process.” The instructor who taught that class at the time, Professor James Lake, who recently retired, had told her about a brand new PhD program at Purdue, insisting, “You should look at it.”

“And I looked at it,” she reports, “It looked fascinating, and it looked really risky, and I wanted to go into industry anyway. But I kept checking back every year on that program to see where were their people going and were they having great impact?” Then in 2013, she decided to go for her PhD.

How was it, an Illinois girl going to Purdue? “Very similar to here,” she acknowledges. “Some great similarities. And it was fun to be in another Big 10 town. But this is home.”

So why the about-face in her career direction? “The dream was to be a professor teaching and researching design, ok? So I guess I've got the dream now,” she admits.

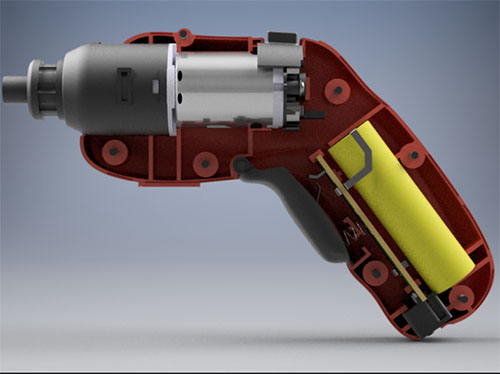

Above: Marius Juston's CAD model of the Black & Decker 4V MAX cordless screwdriver, completed for an SE 101 final project.

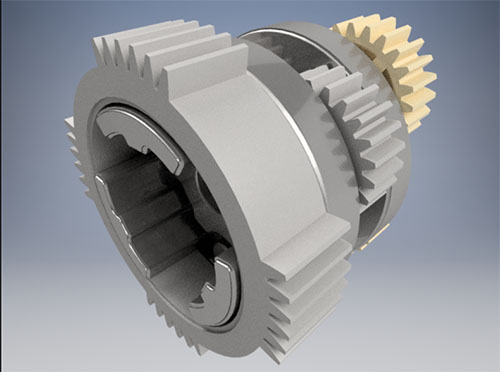

Below: Juston's CAD model of the screwdriver's gears.

To top it all off, she got to come back to Illinois to begin her stint in engineering education. And not only that, she now teaches the course that started it all. She recalls: “This was just the most serendipitous timing that I was graduating, and Jim Lake, whom I had TAed for, was retiring. And it was the class that made me fall in love with teaching. So it was great to come back.”

The course is SE 101: Engineering Graphics & Design, which she teaches every semester, although there are actually two versions of the class. One is product design focused; the other focuses on building design, which lots of civil engineering students take. Goldstein describes how the product design course worked (in a non-COVID-19 world). She and her students would take apart a real product to see how the mechanisms worked and what the mechanical functionality was. Plus, a part of the class was learning a CAD (computer-aided design) tool so they could design. “So that would allow them to get the exact measurement and see how the assembly went together; that's a big part of the class. And an add-on component of that is ‘Now that you have designed it, is there a way that you could think about this from Human-Centered Design? How could you make this better?’”

However, the fall 2020 semester is totally different, with “not being able to take apart the same thing, not necessarily be in the same room, being on different continents,” she qualifies. So this year, she’s doing a very Human-Centered-Design approach that’s situated in K–12. Her students are thinking of better ways, in light of social distancing protocols, to improve the lunch experience for those K–12 students who are in school.

Goldstein shares the nugget of what she hopes her students learn, claiming, “So, as engineers, we iterate, and we use what resources we have,” then explains that the goal of Human-Centered-Design focus is, “To make sure that as engineers, we're solving problems that need solved.” For instance, this semester, “They're starting from the bottom up,” she says, adding that recently her students were interviewing kindergarten through high school students over Zoom, “to understand what it's like right now for them to be eating lunch at school.”

In addition to teaching SE101, Goldstein also is Director of ISE’s Product Design Lab. During a typical fall semester, 18 classes would be using the facility for projects; however, the lab is currently not allowed to operate at full capacity due to COVID-19. But she claims that during normal times, “It's really fun for students. We've got big collaboration team tables. They can take things apart. We've got tools for that kind of thing. Right now, it's not very exciting because nobody can get in; you can't have very many people in at once.” Another draw of the lab is big, expensive machines students can use, such as its 3D printers.

Goldstein shows off some of the objects students have 3D printed in ISE’s Product Design Lab.

So does Goldstein believe COVID-19 has significantly impacted engineering education at Illinois? What about the in-person, face-to-face, human interactions, collaboration and working on teams, doing hands-on projects together—all aspects of engineering education that are difficult to mimic online and on Zoom? What have Goldstein and her colleagues done to counteract these effects, to try to foster that connection that's not there because most everything is online?

Goldstein says Engineering had a huge initiative this past summer, giving instructors resources about things they could do in their classrooms that were based on literature about improved learning methods. For example, her group implemented Classroom Flipping. The idea is that professors record short videos that students watch before class. Then during class time, instructors talk a bit, then have students use Zoom breakout rooms to work in small groups of around four students doing a worksheet or practicing and exploring some problems. Then by the third week of classes or so, class enrollment was more final, so students were in the groups that they'll work with the rest of the semester.

Goldstein claims the challenge she has faced related to COVID-19 is that “learning is such a social process.” She says that, for her, with her large class, it’s “‘How can I facilitate the social process of learning for the students?’ So for me, it's breaking them into small groups, having them do more active learning instead of just staring at the computer, giving them time to interact with their peers and learn from their peers.”

Goldstein by one of the heavy duty 3D printers in her lab.

In both COVID and non-COVID settings, Goldstein claims the biggest challenge she’s encountered in working with engineering students has to do with the iterative design process—identify a user need; create ideas to meet that need; develop a prototype; test the prototype to see whether it meets the need in the best possible way; then begin another iteration: take what’s been learned from testing and ameliorate the design, creating a new prototype and beginning the process all over again until you have the best possible product.

According to Goldstein, “Novice designers tend to not iterate, to use the design language. So their first idea is good, right? They don't want to necessarily come up with 50 other ideas, which one is better, or that they're not necessarily reflecting on what they did. They're just going right to the next task.” Goldstein’s job is “to use her training in engineering education to know what more advanced designers do behavior wise, and encourage those same behaviors.”

So what’s Goldstein’s overall teaching philosophy? She claims a Shel Silverstein poem expresses it best:

Early Bird

Oh if you're a bird, be an early bird and

Catch the worm for your breakfast plate.

If you're a bird, be an early bird—

But if you're a worm, sleep late.

“That kind of embodies what my role is of being coach,” Goldstein acknowledges, “and helping students see what some of their strengths are and what may be perceived as a weakness, and play into those so that they can play into their strengths…I think it just involves helping students reflect on who they are and who they're becoming as engineers.”

Author: Betsy Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photographer: Betsy Innes (unless otherwise noted).

More: 2020, Faculty Feature, ISE, Women in STEM

.jpg)