continued from page 1

Teaching in Prison: The Realities

Quinton Neal, EJP alumnus who works with at-risk kids.

Is there ever a moment when EJP instructors completely forget that they're teaching in a prison and just think of the men as students who want to learn? Replies Ginsburg, "That's most of the time. The time when it doesn't happen is when we're talking about incarceration, thinking about their personal stories, for example. You can imagine… I think most of us would say that we forget all the time." Ginsburg goes on to share an anecdote, "In fact, I've heard stories from EJP instructors that have said they get kind of startled when the officer comes at the end of the class, like, "What's this guy doing here?!"

While the instructors may tend to forget that they're teaching in a prison, the reality is, it is a prison, and instructors and the program itself often encounter challenges not normally encountered, say, on a college campus.

One reality is that some things that are a given in a regular classroom setting are not allowed inside the prison. For example, the robotics instructor couldn't take in kits, like Lego Mindstorms. Thus, they all had to be satisfied with a work-around: EJP students wrote the computer programming, which the instructor then took back to campus, where undergrads would video the robots running the programs. Rather anti-climactic, not to have had the hands-on experience of actually building and operating the robots, but students got to watch a video of a robot performing scripts they had written, which was hopefully somewhat satisfying.

Another reality keeps in check the number of students EJP can serve. Because EJP is limited by space, classes are limited to 15 people. Says Lubienski: "We would love—the big dream!— to have our own building out at the prison." But acquiring additional space in the prison is difficult, plus program staff have to "be careful not to step on other programs' toes."

The space limitation also limits the number of courses that can be offered simultaneously. Lubienski jokes that instructors sometimes compete against each other over who gets dibs on time slots: One announces,"Hey, I want to do a workshop that night,' while another complains, 'Well, I wanted to do this that night!'

Another reality is that although the prison has laptops, it has no internet. Thus, even the logistics of installing and registering software and updates must be carefully thought out. For example, in the new computer lab slated to be opening soon, a sort of "mother-ship computer," along with its networked workstations, will be configured on campus, then taken to the prison.

Closely related to lack of internet is this reality: EJP instructors cannot contact their students in the usual ways. "Once you do start to care about the students," acknowledges Lubienski, "there is no way to see them or have any contact with them other than going out. You can't email them; you can't call them, and they can't drop a line…so the only way to keep involved in their lives is to keep going."

And Lubienski does. In fact, in the Christmas spirit of giving, she once even taught a math misconceptions workshop in late December because, "Over the holiday break, it tends to be a little more lonely than usual in the prison because lots of programs stop."

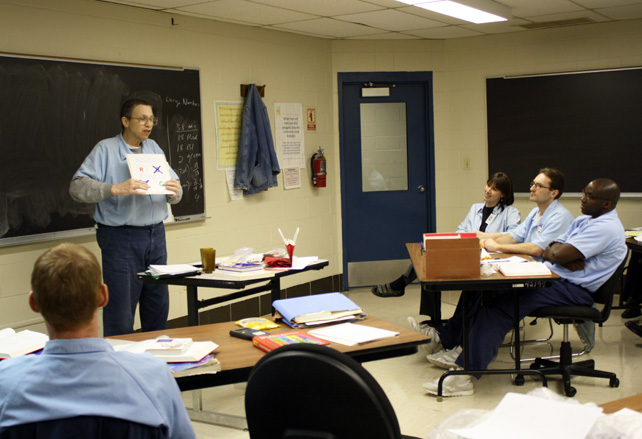

Sarah Lubienski (center) interacts with an EJP scholar while teaching a workshop at Danville Correctional Center.

And Lubienski has never regretted her commitment or involvement in their lives. She admits, "I told my [campus] students that initially I was afraid that when I signed up to teach every Friday night a year ago that I would be tired at the end of the week and be like, 'Wow! What did I commit myself to?' But it was ridiculous how much I looked forward to going out and spending Friday night out there with the students. They are just so eager and excited to learn and committed to learning."

Positive Impacts of EJP

In addition to instructors finding the program personally rewarding, EJP appears to be having a positive impact on not just the students themselves, but their families, and even their communities, once the students are released from prison.

One of the biggest impacts is this: EJP scholars receive actual college course credits from the University of Illinois. To date, around 110 have received credits for courses.

Lubienski describes a recent epiphany regarding this: "One of the rushes for me when I was teaching last semester is: everything seemed quite distant from Illinois until I had to put in their grades. I went in and, sure enough, all of their names popped up on my computer as students of Illinois, and I put their grades in just like I do with my other students. I was like, 'Wow, that is really great!' So they are getting University of Illinois credit, and that is huge."

Another impact is alluded to in the name of the project. For many of the instructors, EJP is an opportunity to personally mete out social justice—to right a wrong. Many see the program as reparation for this injustice: the lack of quality educational opportunities many of these men experienced as youngsters. According to Lubienski, the word alludes to "the vision that education really is a key linchpin for trying to have equitable outcomes for people."

Another positive impact, according to Ginsburg, is that their program is shaping leaders: "We don't just open their heads and pour knowledge and teach them facts, but we try to think of ourselves as more of a leadership institute, and they like to be thought of that way."

According to Ginsburg, EJP students not only consider themselves leaders, but are becoming perceptive, well-rounded individuals: "They tell us they see more clearly and understand better what the challenges are, and they begin to dream of what the solutions may be."

Agents of Positive Change

Former EJP scholar Haneef Lurry speaks at a youth event.

Thus, EJP students not only ponder solutions to many of society's problems; many begin to see themselves as playing a role in those solutions. As they have become better educated, they have undergone a major paradigm shift, which Ginsburg calls, "a big deal," going from an "I'm locked up, what can I do?" attitude to "I may be locked up, but I can better myself and take on some responsibilities in here," to "I have an obligation as a citizen to get out there and make a difference!"

"That's a big shift," says Ginsburg. "The students accept that and they run with that. Most of them seem to gladly take on that mantle of responsibility and have really impressed me with their eagerness to be active agents in positive change."

And part of that involves effecting positive change in their families: "We even see some effects on their own family," reports Lubienski, "whether it's encouraging a nephew or a niece or a son or daughter or sibling in their own education, saying, 'Hey, I'm doing it too!' Those kinds of just rippling effects are there."

Regarding affecting their communities at large, EJP has some poster children who have done just that.

- EJP alumnus Haneef Lurry, incarcerated at 15 years old, spends his free time from his job working with Florida youth, hoping to give them the push in the right direction that he wishes someone had given him.

- Quinton Neal, who spent 20 years in prison, has founded TSO Squared (Teens Speaking Out, Teens Stepping Out), working to get at-risk kids off the streets into educational, extracurricular programs.

- Israel Gonzalez, upon his release from prison, was deported to Mexico. But because of his training through EJP's ESL Program, his job visiting schools to sell classroom tools led to a permanent job teaching in his own classroom.

Dreams for the Future

EJP alumnus Israel Gonzalez teaching in Mexico.

Regarding the future, Lubienski has big dreams, both for EJP scholars and for the program itself. On a practical but extremely crucial note: she hopes her students can find jobs. "I guess that one dream would be that when our guys do get out, that they are able to find employment that they can really use their skills and knowledge. I know that they will face some obstacles in the hiring process because of their backgrounds, but if I had a business, I would hire every single one of these students with no hesitation."

Another dream is related to the program itself. Right now, EJP is a miscellaneous compilation of courses based on what people volunteer to teach, and students cannot work toward a degree. "So one dream that we have is…an interdisciplinary, perhaps education studies major that the guys can actually earn a bachelors in before they leave."

Ginsburg also has big dreams: she too wants to build a new building at the prison. "The building that we're in, we're running out of space, and there's a natural limit to how much we can do." For example, the room in which they performed The Tempest has a capacity of 75; since there were 20 performers, only 55 people could be in the audience. She would like a new building with classrooms, and a room that could work for theater and assemblies.

Along with a new building, Ginsburg dreams of institutional support in the form of recognition of the Danville campus as a venue for University programs, activities, and courses, thus making it easier for instructors to get course release when they teach and possibly facilitate more people coming out to the prison.

Ginsburg also wants the number of people the program serves to grow. While not all the men at the prison qualify to be EJP students, she envisions them being involved in some capacity: "I want it to be the case where there isn't anybody at Danville prison who isn't touched in some way by this program…So, I imagine in my fantasy, that the whole prison becomes a site for reflection for intellectual growth, and for intellectual learning community."

Story by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative. Photos courtesy Rebecca Ginsburg and Elizabeth Innes.

More: Champaign-Urbana Community, Underserved Minorities, 2013

EJP student presents during a class taught by Sarah Lubienski.

.jpg)