Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti Passionate About STEM Outreach, Cooking Up a Multidisciplinary Masterpiece

“I love multidisciplinary work. I think that brings the best of every world together. It's like cooking. You get all of your best ingredients, and if you know some type of cuisine and you can combine it with another, you can cook something great.” – Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti

MechSE Assistant Professor Jie Feng and Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti demonstrate the bubble activity for youngsters at the Orpheum.

August 8, 2019

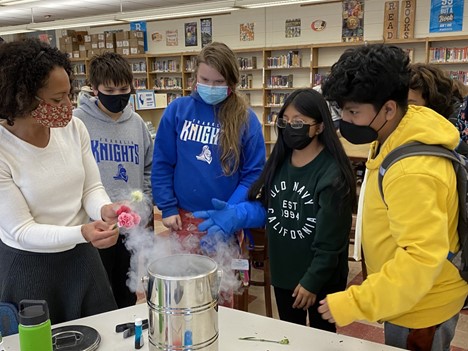

When high schoolers in the WYSE (Worldwide Youth in Science and Engineering) camp were struggling with how to insert a bubble inside another bubble, Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti was there to help the students trouble shoot. And when youngsters at the Orpheum Children’s Science Museum’s Creative Science Camp couldn’t get the wand they’d designed to make rectangular bubbles, she was by their side, effervescently encouraging them to follow their intuition. Extremely passionate about multidisciplinary engineering, Salazar Coariti is just as passionate about STEM outreach. So she got involved with the two summer 2019 outreach opportunities in hopes of helping the youth build their scientific intuition.

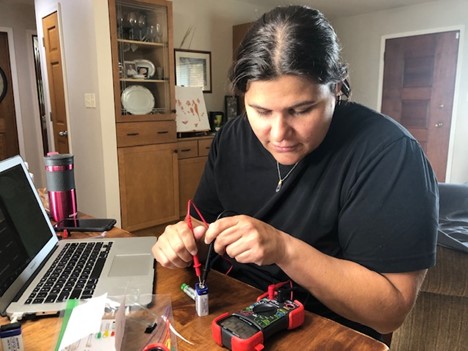

Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti

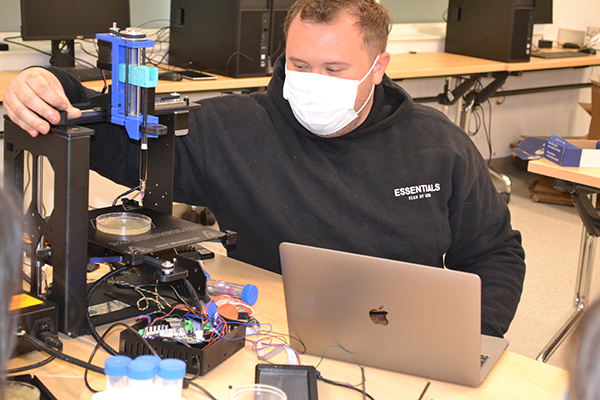

Salazar Coariti received her Bachelor’s Degree from Illinois’ MechSE Department in December, 2018. She currently works in NCSA’s Nano Manufacturing Node as an Assistant Project Coordinator and Research Scholar, and hopes to apply to grad school at the end of the year. Her goal? To become a professor someday. But while her work is currently in nanotechnology and optics, her goal is quite interdisciplinary.

“I would like to do some type of joint technology. So I would like to help with physicians and doctors and just provide them with good technology for their medical needs.” She intends for her work to be very interdisciplinary. “So, learning a little bit of optics or learning a little bit of different things really I can help create a device for doing all of that. So that's why I'm very open with the research that I pursue, because I know everything can add up to the big picture.”

In addition to her interdisciplinary emphasis, Salazar Coariti is also passionate about STEM outreach. She explains why. “So I think I have been blessed to have this opportunity—to be able to have higher education and just have all of this. And so that's been always my motivation, to make these things more available to people. And I know that not all of us grew up in an environment that has maybe an engineering side of it. And so making this available to other people in a way that they can understand, it has been one of my passions as well.”

So in a fortuitous meeting with MechSE’s Outreach Coordinator, Joe Muskin, she learned that they share a mutual passion for STEM outreach, heard about some of the things that he does, and volunteered.

“I was very excited about it, because, you know, just being able to help children have more intuition in science was something that I was very excited about.”

Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti (right) holds a 3D bubble wand which she has immersed in the soap solution in order to demonstrate to the participants how it should work.

So when MechSE Assistant Professor Jie Feng shared the bubble dynamics aspect of his research at the Mechanical Science and Engineering (MechSE) session of the summer 2019 WYSE camp, and then again at the Orpheum a few days later, Salazar Coariti was right by his side.

In fact, she made significant contributions to the activity’s design. “So I was able to just do the experiments on my own and see ‘What are the best types of solutions for the bubbles?’ so that the students would be successful, and then how to manufacture the shapes the best possible way.” For instance, she discovered that basically, bubbles are spherical, “Except you can manipulate them by the shape you use,” she adds. She also discovered some of the down sides and the up sides of each way of manufacturing them.

Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti (right) works with a youngster during the Orpheum outreach.

A young girl at the at the Orpheum outreach uses the 3D wand she designed to make bubbles.

The idea behind the activity was to create different polygon shapes, immerse them into the soap solution, and see some type of formation that is different. (As in the case of the cube, you should ostensibly see a square.) “And so after that, what you do is you blow a bubble, and the bubble will be constrained within that surface station. And so that's kind of why it happens.”

It was to be expected that the little kids would get a kick out of the activity. I mean, what little kid hasn’t spent hours delightedly blowing bubbles with a little plastic bottle and its bubble wand? But the high schoolers appeared to be just as engaged as the little kids.

“They were very engaged,” Salazar Coariti agrees, and believes that the strength of the solution, “making this solution so that it doesn't break easily,” was key. She reports that the solution they came up with could be used to make huge bubbles. “So I thought, if this is too easy for them, then they could still have fun with the fact that they can make big bubbles!”

Calling the activity “a good project, actually,” she believed the guidelines they gave students provided enough challenge. “It's nice to see how people came up with different ways to solve this problem, because we gave them the challenge, ‘Can you make an honest vertical bubble?’” She says they first tried using different types of shapes for the holders, but that didn't work out. Then they started trying different things, and at the different tables, one could see each group’s approach to this problem. “There was a team that made a bunch of bubbles next to each other so that the ones inside didn't have this very cut shape. Okay, so that was another way to solve the problem. So it was just interesting how everybody had different ways to approach this,” she states.

WYSE high school students blow bubbles out of the wands they created.

The diversity of strategies also helped her in her as role teacher. “I was able to have an empathy with the students and see how we could help them to go to the next step and guide them.” She adds that this is also important when collaborating with someone else in research, because there will always be miscommunications or things that can happen. “And so seeing it from the perspective of, ‘We just want to each other to succeed,’ I think that allows for better communication.”

She shares why the bubble activity was also good for the younger kids at the Orpheum. “Because it builds intuition,” she explains. “So when you start studying engineering or any type of science, there is always, something—an experience that you had previously—that will allow you to build more knowledge on top of it.” She believes having those types of activities helps them build that.

Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti (right), interacts with a youngster at the Orpheum.

For example, when some activity works, they tell themselves, “Oh, yeah, this is correct! I can do this!’ Then as they have more exposure to a certain type of activity, “It helps them build more neural networks and have a good grasp on difficult concepts that are sometimes non-intuitive in science. But having been able to see an experiment, ‘Oh, yeah, I cannot make another spherical bubble by just shaping everything in a different way. I need something else.’ So that helps them, I think, especially if they also want to pursue a degree in engineering, and maybe if they don't, this may inspire them to see, ‘I can also be a scientist.’”

As passionate as Salazar Coariti is about inspiring young people, does she think there’s any teaching in her future? “I'm hoping so,” she admits. “If God allows me to go into research and just be a professor and all of that, I'm hoping to be able to help students, just build up the intuition if they don't have it, or if they do, help them to improve it, go even farther with that. So I hope someday I'm able to do that.”

She also hopes to be able to show students who have convinced themselves science or engineering is not for them just how fun it is. “There might be people that might not be able to understand science and sometimes they close the door to it because they think, ‘This is not for me. Math is not for me. I didn't grow up like that!’ But I want to maybe someday make it accessible also to them as something that is fun. And I think doing it with kids also helps the fun to be there.”

Salazar Coariti says that although she didn’t participate in any activities like this when she was a kid, she ended up mechanical engineering because when she was young, she loved physics. “I wanted to be a physicist, but my parents thought it was not serious enough…my parents were not into engineering at all.”

Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti on Bardeen Quad outside of the Mechanical Engineering Lab.

Salazar Coariti admits that it was an interesting discussion when she told her parents, “’Oh, I want to do engineering.’ They were, ‘How? Why?’ Her parents thought something like business would be better for her in the long run. For one, they didn’t really have a good understanding of what engineering is, and thought mechanical engineers only repair cars or trains. “So my parents were like, ‘I don't think you're gonna enjoy this!’ But she says, “Engineering is something that is cool, and mechanical engineering allows me to have an understanding of the world in the mechanical way, I guess.” She figured that since she liked mechanics lectures in physics, Mechanical Engineering might be a good fit.

However, when she goes for her Master's, she’s thinking about either biomedical or electrical. “I think that would be awesome to just do all of the devices that I would like to be out there,” she says. She’s also considering electrical, “Because I would love to have more understanding of the electrical parts of things. I think that would be very good. Just combining different knowledges together.”

She envisions using all of her multidisciplinary experiences in biomedical engineering to help people—to make a difference in people's lives in the medical arena. “That would be amazing if I get to do that,” she says. She envisions moving beyond the limitations of any one field to create innovative devices. She shares a metaphor of an artist going beyond traditional boundaries: “So as an artist, if I can paint with paints, I could paint with other things and use all of my techniques to create something. So I feel the same way when it comes to designing something. If I have more knowledge of different things, then I am able to create something that can help other people.”

Salazar Coariti believes the multidisciplinary aspect is key. “Yeah,” she admits. “I love multidisciplinary work. I think that brings the best of every world together. It's like cooking. You get all of your best ingredients, and if you know some type of cuisine and you can combine it with another, you can cook something great.”

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative, unless noted otherwise.

For additional istem articles about Adriana Carola Salazar Coariti, see:

For more related stories, see: Illinois Legacies, MechSE, Student Spotlight, Women in STEM, 2019

WYSE High School students experimenting with their bubble wands.

.jpg)