Center to Study the Effects of Toxins on Children, Then Educate the Public

Susan Schantz, Professor of Comparative Biosciences and PI to the new Children's Environmental Health Research Center grant.

March 19, 2014

Like most folks these days, I make an effort to be green. However, I'm not a fanatic. But when I-STEM's director, Lizanne DeStefano, announced one day that, as a result of evaluating a new grant studying the effect of toxins on children, she had gone home and thrown out all of her Tupperware, this reporter's curiosity was piqued, and as a result of chatting with Susan Schantz about her project, I may mend my ways.

Co-funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), a 5-year, $7.6 million grant was recently awarded to Illinois' Children's Environmental Health Research Center. The project, "Novel Methods to Assess the Effects of Chemicals on Child Development," is studying the effects of phthalates and BPA on children.

As defined by the CDC, phthalates (often called plasticizers) are a group of chemicals used to make plastics more flexible and harder to break. BPA (Bisphenol A) is a chemical building block used primarily to make polycarbonate plastic, such as in reusable food and drink containers, and epoxy resins, used as protective liners in metal cans of canned foods.

According to PI Susan Schantz, the grant is recruiting women in the first trimester of pregnancy, then will follow their babies from birth on to look at health outcomes related to prenatal exposure to these two chemicals. This grant was awarded based on results from a smaller, 3-year pilot project studying phthalates and BPA. So, in addition to the 180 women who participated in the original pilot study, the new study is recruiting 600 more; plus, they have added in a community outreach component.

How will Schantz and company gather data about the effect exposure to chemicals has on babies? Unlike with rats, these researchers wouldn't knowingly expose pregnant women to potentially harmful chemicals for the sake of their research.

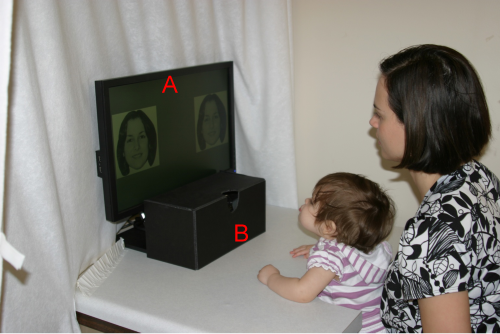

Sexually dimorphic indices (i.e., measures that differentiate boys and girls) including anogenital distance and second to fourth finger ratios are measured at birth. (Image courtesy of the Children's Center website)

According to Schantz, "Everybody is exposed to these chemicals, right? Phthalates are in so many personal care products and home products that virtually 100% of people are exposed on a daily basis; BPA, over 90%, because it's used in a lot of food storage, food contact applications. So it's almost impossible to avoid exposure to either one of these."

Schantz's human research involves looking for correlations between exposure and outcomes. "We always have a range of exposure in a population, and that helps us see if people with higher exposure have more adverse outcomes than people with lower exposure."

How do they measure exposure? Like your physician routinely does in certain medical tests, the researchers collect urine samples. Five times throughout each participant's pregnancy, they measure the BPA and phthalates in the urine. They are also doing a product-use survey; each time they collect a urine sample, they interview the woman about products she used over the last 24 hours. So in addition to the health impact for babies, the study will look at the sources of exposure.

Schantz explains that this is the approach normally used when looking at chemicals with a short half-life, which she defines as "how long it takes a chemical to be broken down in a body and excreted."

So the good news is, they don't accumulate in our bodies: "So it's not like, the longer you're exposed, the higher the levels in your body get," says Schantz. "It's not that it's building up." The bad news is, "You're exposed every day, day-in, day-out. You can't avoid it."

By now, the reader may feel Schantz's research is hitting uncomfortably close to home. Most likely, just about everyone has left-overs in their fridge right now, stored in plastic containers. (I do.) Does storing food in plastic containers cause these chemicals to leach into the food?

"The research isn't really very complete on all these different things," admits Schantz. "We know that it can leach out of food storage containers, and it's probably worse if you heat it, or if the plastic is old and scratched up." (Note to self: 1) don't microwave in plastic; 2) get rid of 20-year old Tupperware; 3) better yet, invest in glass storage containers.)

These canned foods were most likely processed with epoxy resin liners that contain BPA.

Schantz introduces another dilemma: BPA is leaching into our canned food.

"One of the biggest issues is that BPA is used in the epoxy resin that's used to line metal food and drink cans. There's really no substitute for that at present, so virtually all metal cans have it. So, you can store your own left-overs in a glass container, and that's great, but if you're going to eat canned food or drink a coke out of a can, there's going to be BPA. It seems like, from the research, if it's something acidic, it's going to leach more [such as the canned tomatoes commonly dumped into chili?]. One of the things that has been shown is that people that eat a lot of canned food have higher BPA exposure, so we are getting it from leaching out of cans."

What about frozen food? It's stored in plastic bags. Are those suspect? Schantz clarifies that there are different kinds of plastic—and soft plastic isn't the culprit. BPA is mostly in hard, clear plastic or hard, colored plastic.

Hard, colored plastic—such as the plastic used to make children's dishes? While Schantz says most of those are BPA free now, we shouldn't breathe a sigh of relief just yet.

"Just because it's BPA free, it's really unknown," she qualifies, "because there's all these other chemicals that are similar to BPA…BPS and BPF. We don't really know if they're better or worse than BPA, but in things that are BPA-free, they're replacing the BPA with something." (Note to self: Google stainless steel children's dishes.)

She cites a small study that had people eat only fresh foods, then canned foods, and looked at the difference. "They could see their BPA levels going up and down, depending on whether they were eating the canned or the fresh."

Schantz keeps adding to the list of taboos. Regarding phthalates, one called DEP is used to stabilize scent in scented products, like perfume, and most likely dryer sheets.

By this time, the reader might be feeling a bit overwhelmed regarding toxins in our environment. Has researching ubiquitous toxins her entire career made Schantz paranoid? Let's say cautious.

Fragrance-free baby shampoo

"I've always been kind of a stickler, mainly because I have so many allergies," admits Schantz. "And even before I knew much about phthalate, I was always using fragrance-free products. My daughter when she was little had really sensitive skin, too, so I started using fragrance and dye-free everything."

A note of caution: she urges, make sure it's fragrance free. "There is a difference between fragrance free and unscented. Unscented has fragrance in it; it can still have phthalate in it."

Schantz can trace her interest in environmental health all the way back to graduate school. She started out in psychology, but, at some point, got interested in environmental health and got her Ph. D. in environmental toxicology. "I always focused on the nervous system and brain development and cognition and how environmental chemicals can affect that. So I kind of put these two interests together at an early stage of my career."

While she loves the research, Schantz is also motivated by a desire to help her fellow human beings. "I love research, and I love doing science, but I've always wanted to be doing something that I can see is relevant to human health and making a contribution to human health."

And she's found kindred spirits in the Children's Center Program, which has been in existence and addressing children's health since 1998. What makes the Center unique, according to Schantz, is its parallel animal and human research. For example, Janice Juraska in Psychology directs a project and looking at neurodevelopmental outcomes in rat models; Jodi Flaws in Veterinary Medicine's Comparative Biosciences directs a project looking at the impact of these chemicals on male and female reproductive health and reproductive development. Susan Korrick leads another human study investigating the effects of phthalate and BPA on adolescent neurobehavior.

Why the emphasis on BPA and phthalates? According to Schantz, there isn't a lot of research on their effect on humans; studies have only begun to be published in the last 3 or 4 years, and most of the information available is from animal studies. While Schantz studies humans, she says both types of studies are crucial.

"The animal research that we are doing as part of our children center is really, really important. It's a key part in what we are doing. But just animal studies alone are not enough. Rats are not little humans, and there are certainly differences in how chemicals are metabolized. So you have to have the human studies too."

Based on research so far, what about BPA and phthalates could be harmful to humans?

While Schantz admits, "We know way, way less than things like lead and mercury, as that's been studied for a long time. So we're kind of at a pretty early stage researching these chemicals. But we know they are both endocrine disruptors." For example, animal studies have found that phthalates can reduce the production of testosterone. In some circumstances, BPA is estrogenic and can have effects similar to estrogen. Schantz says that hormones like estrogen and testosterone are important in early brain development; exposure can impact the brain as well as the reproductive system.

"All of these chemicals are called endocrine disruptors because they don't really affect just one hormone, they can disrupt various hormones or maybe depending on the circumstance or the tissue in the body that you are studying BPA can be anti-estrogenic or estrogenic or it can affect the thyroid, and thyroid hormones are very important for brain development, too. That's one of the reasons we're focusing a lot on neurodevelopment and our studies."

While this reporter got to sit down with Schantz and pick her brain regarding toxins and their effects, the general public most likely won't have that opportunity. So the Center will be conducting education outreach, such as making child-care professionals aware of environmental health risks. Also, educational materials regarding toxins may be accessed via the Center's website. In addition, for those interested in Schantz's results, the EPA has a webinar to disseminate information regarding work related to children's health and chemicals. The EPA/NIEHS Children's Centers Webinar Series is held on the second Wednesday of each month from 1:00-2:30 pm EST/EDT. The webinars are open to the public, so anyone can call in, listen to the presentation, and ask questions. (Schantz will be presenting in a webinar next fall.)

What are the results so far? "We have a pretty broad range of exposure in our population. A lot of the women that volunteer for this study are well educated and concerned about their health. I think some of them are pretty careful about exposure and maybe others less so."

And finally, what impact has being educated about these two toxins had on this reporter? I have not yet replaced my plastic storage containers with glass, but I intend to. Further, the day I wrote this article, I ordered several sets of stainless steel children's dishes for my grandkids.

Story and photographs (except where noted) by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Faculty Feature, Funded, Women in STEM,

2014

.jpg)