Brady STEM Academy Provides Role Models for Local African-American Boys

March 5, 2014

Left to right: A BTW student, Jerrod Henderson, and Lonna Edwards measure the voltage of a "potato battery" the student made during the Brady STEM Academy after-school program.

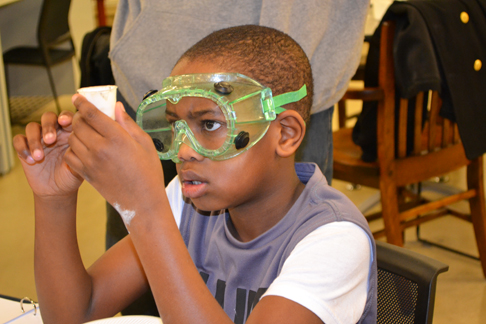

A young BTW student appreciates the effectiveness of the "apple battery" he created.

Some outreach-minded folk in chemical engineering have begun a new after-school program, the St. Elmo Brady STEM Academy, hoping to make a difference in the lives of local African-American boys. While programs providing hands-on STEM activities happen fairly frequently at Booker T. Washington STEM Academy (BTW), what sets this program apart is its emphasis on African-American role models— including the boys' own fathers.

This unique aspect—the idea of involving fathers—came from a program Dr. Jerrod Henderson, a faculty member in the Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering Department, and Ricky Greer, a specialist in K–12 education, recently created then piloted at the Don Moyer's Girls' and Boys' Club. Regarding the fathers' involvement: "It had a great impact on the kids and their excitement," recalls Greer, "and we really enjoyed seeing the fathers get down on their hands and knees and work on the projects with their sons."

Something else they learned during the pilot program? "Short bursts of programming tend to work really well," indicates Henderson. Thus, the STEM Academy will run for eight weeks with three sessions a week—one intentionally held on Saturday so the boys' fathers can attend.

However, while involving fathers is an important aspect, for some young participants, the father might not be in the picture; thus, the second program component involves recruiting Illinois graduate and undergraduate students to mentor the young participants.

"We realize in the target population, the father is not always there," admitted Henderson, "and so that's why we said, 'Let's get the mentor piece in there.'"

The third member of the team, Allante Whitmore, a Ph.D. student in Agricultural & Biological Engineering, indicates that student mentors will also serve as role models to demonstrate that, "Hey, I'm going to college. You can do it too."

According to Whitmore, young participants will "get a good relationship with someone who is in higher education, and get exposed to that in the event that their father might not have gone to college."

Mentoring was also included because each team member could look back and see how important certain people were in helping them get to where they are today. "I think that's all centered around that mentoring piece from each of our lives," says Henderson. "We speak about how mentoring was important and crucial for our success."

A participant at the Saturday lab session makes slime, assisted by Cornelius Lawson, one of the program's mentors.

A third way the program will incorporate role models is during the activities themselves. While addressing a different topic each week, the team will showcase a multicultural scientist who has contributed to that area, such as the program's namesake, St. Elmo Brady. This emphasis on African-American scientists who paved the way was added because of the positive role models they can be for students of color. For example, Henderson shares an anecdote about how Brady's career impacted him personally.

Henderson recalls that during his years as a graduate student at Illinois, he used to gain inspiration just walking past the photo of St. Elmo Brady that hangs in Noyes Lab. Henderson stresses that minority students, like the young men in their program, even undergrads and grad students, rarely are exposed to role models of their own race.

"People who look like them…are few and far between in science. So for me as a grad student, I remember we were walking by this poster, and it just encouraged me to read about this guy."

The team's decision to name their program after the famous African-American chemist seems more destiny than serendipity. In fact, according to Henderson, "The connection is really spooky."

St. Elmo Brady was the first African-American Ph.D. in the United States. He graduated from…Illinois. Not only that, but he taught at Ricky Greer's Alma Mater, Tuskeegee University, and was mentored by its founder, Booker T. Washington (extremely apropos since the program is at Booker T. Washington STEM Academy).

Another famous African-American they will showcase is Mae Jemison, a physician, college professor, NASA astronaut, and the first African-American woman to travel in space. (Interestingly, her fascination with space was sparked by a role model she had growing up: Lieutenant Uhura on Star Trek, portrayed by the African-American actress Nichelle Nichols.)

To ensure the program's success, the team insisted that the children chosen to participate would actually be interested in STEM.

"We wanted children who wanted to be a part of the program and were not made to be a part of the program," Henderson emphasized, "because their attitude towards the program is different."

So how did they recruit the kids? BTW teachers identified around 40 students who show potential in and are excited about STEM, then parents were asked to fill out an application. Based upon those two criteria, they narrowed the field down to 20 participants.

The program is targeting 4th and 5th grade underrepresented males, hoping to get them interested in STEM early. Henderson admits that they specifically chose that age group to counteract a dislike of STEM that often crops up around that age:

"Yeah, this 'I don't like math; I don't like science' complex of many of the young people that I have come across—by 4th grade, they decide that they can't do it, and they've been told that they can't."

Allante Whitmore looks on as a student gathers data to determine which makes a more effective battery: a potato or an apple.

Allante Whitmore looks on as a student gathers data to determine which makes a more effective battery: a potato or an apple.

Ricky Greer demonstrates an experiment they might perform for Brady STEM Academy participants.

While the three hope to lure some young men into the STEM pipeline, they admit that one reason they're doing the program is they just plain love teaching.

Whitmore, no stranger to STEM outreach, admits that she enjoys it because she loves to teach. Her career goal: become a professor, then use her position to offer outreach in whatever community she ends up. "Outreach is definitely my passion," she admits. "I love just watching students learn something; their eyes light up when they understand something, and I've always enjoyed it."

Henderson admits that he's always wanted to teach: "From early on, I knew that I wanted to be a teacher. So I had mentors in my life that pushed me towards, 'Well, if you want to teach, this is what you're going to have to do. It was always those mentors that had an outreach component to what they were doing.'"

So like the mentors who helped him, Henderson wants to lend a hand to some youngsters in this community:

"In my community, in the colleges where I attended, that's the culture. You give back to your community, and I was raised with that. You don't think twice about it. That's what you're supposed to do; you reach back and you help others."

The team's personal goals for the program are varied. Whitmore acknowledges that there's often a disconnect between the University and the African-American community, because its students or parents are often used for research. So she hopes "to give something rather than receive something. I think that that is a personal goal of mine, to improve the relationship between the university and the African-American community."

Greer particularly wants to reach out to young African-American males: "I feel that if we can show them that there are African-American men who are successful…You just have to work, and be that mentor, and show them that it is possible to be successful…And again just having a passion for the community and wanting to uplift the community."

"I want to expose these young people to STEM," says Henderson. "But beyond STEM…whatever career path they choose, I feel that they are going to look back and say, 'I remember when I was in this program, and these people really helped to push me and encourage me.' And it'll go a long way. I'm just a proponent of exposure."

Henderson goes on to share how some of the things he was exposed to as a youngster influenced his becoming a chemical engineer:

"I always liked science, for some reason," he confesses. Maybe it's because as early as 6th or 7th grade, he was going to engineering conferences. Leaders of his community's mentoring program said, 'We're going to give these kids something to do!' So they took him and other kids to college open houses and football games—even the Black Engineer of the Year Awards. A STEM conference, it had a career fair, so he and the other kids rubbed shoulders with scientists and engineers. "I didn't really know what it was," he admits, "but I said, 'Oh, this seems pretty cool.'"

Henderson envisions a scenario in which his mentoring program might have that same kind of influence in these youngsters' lives: "While we might expose them to STEM, they might also get the chance to travel to these conferences that we have talked about. They now may get the opportunity to sit at a banquet table, and we'll show them, 'This is how you use this fork and this knife.' So all of that, because you're exposed to something different. You get those new experiences. They learn things like what a black tie event looks like. And all of it came about because they were part of a STEM program."

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Booker T. Washington, K-6 Outreach, Underserved Minorities, 2014

Jerrod Henderson helps a youngster with his potato battery during one of the program's sessions.

A young BTW student does a hands-on activity about the states of matter during a Saturday session of the Brady STEM Academy.

Left to right: Allante Whitmore, Jerrod Henderson, Ricky Greer, the team that created the St. Elmo Brady STEM Academy.

.jpg)