Next Generation School Fair: Tomorrow's Scientists & Engineers Meet Today's

Pint-sized scientist-in-the-making explains her science project to Illinois Psychology professor Kara Federmeier.

March 8, 2013

When Next Generation School needed some people knowledgeable about science and engineering to serve as judges for its 2013 Science and Engineering Fair, it didn't have far to look. Lucky enough to be in the same community as a world-class university, the school found plenty of folks willing to donate some time and energy to help shape some of tomorrow's scientists and engineers.

So excited about the fair that a bunch of them showed up at 7:30 am the morning of the February 15th event, Next Gen's intrepid students stood toe-to-toe with 20 Illinois scientists and engineers, some of whom fair coordinator Carrie Kouadio calls "rock stars in the science ed world." Undaunted by the judges' reputations, students eagerly explained their projects and what they had learned and answered questions.

Primary science lab co-teachers Kathy Feser and Ashlee Kozak report that their students love this interaction with the University folk. Kozak recalls that after last year's fair, some of her students were boasting: "I got to tell so-and-so; I met this person," and believes this interaction with real-life scientists has a positive impact on her students.

Next Gen student explains her project to Illinois research engineer Keng Hsu.

"That kind of gets them interested in the sciences more, because we do have some kids that aren't…But it gets them even more [interested], because I think the judges tell them what they do and how maybe what the student is doing relates to their field and what they are working on in their lab."

Says Feser: "Anytime you have somebody come in that's not a classroom teacher [it] makes it special...I think they love it, interacting with other people. And it's really important for them to do so." Nano-CEMMS education coordinator Kouadio, who coordinated this year's fair, actually helped start the Science Fair three years ago when she worked at Next Gen. Kouadio admits that the idea for the fair was stolen from another school, but says they improved on it and "actually took it up a notch, because we have judges who are from the STEM community, which is a big deal for us." And the fair was so successful that the school decided to keep doing it.

Unlike most science fairs, where students do a project at home and bring it the day of the fair, students were prepared during the school day. Kouadio believes this extra teacher input ensures high-quality projects. "Everybody comes to the fair with a good project, not just those who have a lot of support at home."

Science Fair coordinator Carrie Kouadio discusses Next Gen student's project with her.

Also unique this year, while the primary students' projects weren't necessarily connected to their curriculum and could be either science or engineering-based, the middle school projects were connected to their Project-Lead-the-Way curriculum on engineering. Kouadio indicates that this engineering focus "reflects the new Next Generation Science Standards that are coming out…so we wanted to move in that direction because it's becoming more of a priority nationally, and we just thought this is a good direction to go."

Primary science teacher Feser reports that some students were quite excited about the engineering option. "I think it is going to open up the world for the children…Some of them don't love science; they see science as not connecting with them. But once we start to say, 'Engineers do all kinds of things; in fact, there are engineers that engineer food!'" this evidently elicited a "Gasp!" from some of the little girls—budding food engineers who are excited about recipes. "But it's true, you can be an engineer in so many different ways; I think it really broadened it for some of the kids…We have two little girls comparing cupcakes. It's certainly something food engineers probably do."

Two Next Generation students discuss their work with Illinois judge Kara Federmeier.

While most students did individual or group projects; the kindergarteners and first graders did whole-class projects. For example, kindergarteners investigated what makes seeds sprout, using variables like dark vs. light, cold vs. warm, and wet vs. dry. Each child prepared their own seeds, then self-reported their data, which they would eventually compile to construct a bar graph made of pieces of paper.

According to Feser, the kindergartners found unwrapping their seeds almost as exciting as opening presents. "It's very chaotic," she acknowledges, "but it's very exciting when you get to unwrap the seeds. It's not like a birthday but…you know? So the first day we did dark and light. And the seeds were willing to sprout in both, of course. But we had more sprout in the dark, which was really a curiosity to the kindergarteners because they really felt like the seeds needed light to sprout since plants need light."

Do the teachers divulge what the results should be? Nope. They want the kindergarteners think and ask questions: "So, we haven't given so-called right answers, because we want it to be an investigation."

According to Head of School Chris Bronowski, that is one of the school's goals regarding the science fair: to encourage their children to learn to think outside the box. "That is the emphasis of Next Generation, inspiring children to think—and to think creatively. Because you can learn all the facts about science and engineering, but if you can't think about them and apply them in a new and creative way, then you have a lot of knowledge."

Bronowski also adds that they not only want help their students think creatively, but to also teach them to persevere when they encounter obstacles—just like real scientists. "It really serves as inspiration for our students, helping them to learn how to think outside of the box and also give them a little bit of freedom in pursuing their own interests and ideas and to also learn that process of, "Oh this is not going at all the way that I thought it was going to go."

Ashley Kozak and Kathy Feser, Next Generation School's Primary Science Lab co-teachers.

In fact, this is one reason the school chose Project Lead the Way curriculum. Shares Bronowski, "When we went to a seminar, they said, 'Your students will be uncomfortable with this, and they will fail with this, and that is the way it is designed, because they need to learn how to push through those failures to gain that knowledge and move forward.'"

Does the fact that there is no clear winner detract from the kids' excitement? Feser thinks not. "They know their exhibit is going to be put in the gym with 120 other exhibits, and we talk about having pride in what you have up. So I think having their work out there in the public view is probably more important than necessarily being the one winner. You can only have one winner if you give out a prize, where I think our kids are saying, 'This is my project.' A lot of them have a lot of ownership to their project…That's what we're trying to get across. 'You have a story to tell. The story has to be on the board. You tell it in your way, and everybody's going to get to see it.'"

Hoping to impart their love of science to their students, Feser, whose bachelor's degree is in civil engineering, and Kozak, whose bachelor's degree from Illinois was in chemical engineering, both changed careers mid-stream when they discovered that they love teaching youngsters about science.

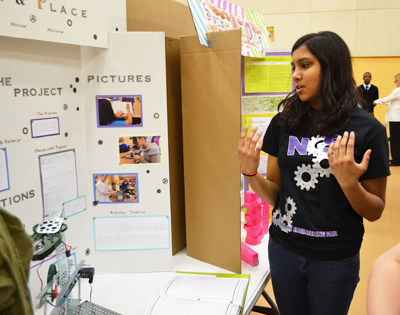

Next Gen middle school student discusses her robotics project, entitled "Pick and Place."

Says Feser: "I hope it influences them. We did hear from one dad that his daughter has come home and talks about science all the time, and not just through the fair, but through the year." Kozak admits that this report was reassuring: "That made us feel good," and acknowledges, "It's a new curriculum this year…"

Feser continues, "I'm hoping with all of what we're doing there are more kids who find science accessible, and find science interesting and fun."

With the school's strong emphasis on science, does Next Gen's Head of School Bronowski hope they all become scientists? "No, no, that is not what I want for any of our students. What I want is for each one of them to be the absolute best that they can be. Whatever that is, I want them to have the foundation and the inspiration and the confidence to do whatever it is they decide their way in life is, and for their education to support them in their endeavors and not to ever hold them back."

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: K-6 Outreach, 6-8 Outreach, Next Generation School, Science Fair, 2013

For further information regarding Next Generation School's partnership with the University of Illinois, see these additional I-STEM articles:

- 2016 NGS Science & Engineering Fair Fosters to Research/Presenting to Experts

- BTW Kindergarteners Have a Ball Learning About Polymers, Manufacturing.

- Local Teacher Uses Project Lead the Way to Prepare Next Generation of Engineers;

- MechSE Gives Back to the Community.

Chemistry professor Don Decoste discusses science with a Next Generation student.

.jpg)