Next Generation School’s New-Look Science and Engineering Fair Imparts the Same Old In-Depth Learning and Life-Long Skills

Febuary 28, 2019

Psychology Professor Kara Federmeier (right) watches as a Next Generation student demonstrates how the facial recognition software his project was about works.

"Courage to Be Curious," Next Generation School’s Science and Engineering Fair on February 15th, had a bit different look than in previous years—you could see from one end of the gym to the other! What was missing was the roomful of large display boards on which students had explained their research in the past. In their place were laptops, which the older kids (4th grade and up) used to present their research on websites they’d created using Weeble, an online platform. Other than that, it was exactly the same. As in previous years, it was the highlight of the year for scores of excited kids who presented to community experts. Also as in previous years, there was no 1st place winner, but every child was a winner as they learned more about their chosen topic, embraced the scientific method or engineering process, and gained communication skills…including learning how to make a website!

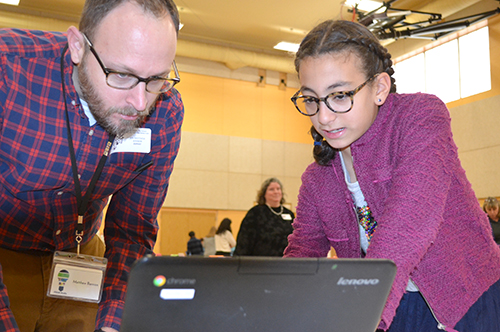

A Next Generation student shows community expert Matthew Bannon (left) the website she designed for her project.

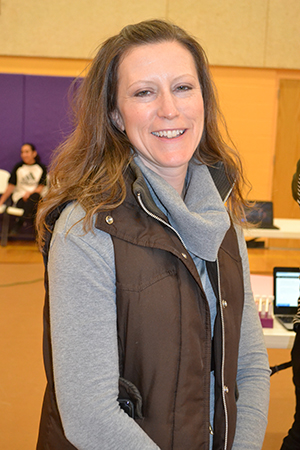

Head of Next Generation School, Chris Bronowski.

Regarding the big change this year, Head of the School Chris Bronowski reports that every year, she and her team do a post mortem after the fair is over, asking themselves, 'What can we do to make it better?” After last year’s fair, they decided it was time to make a change regarding students’ presentation style, explaining that when their students get out into the real world, “They’re not going to be creating display boards. They will be creating websites and using technology to communicate what they have done.’” Given the centrality of the internet in our society, the idea was to arm the students with skills that they’ll be able to use their entire lives.

Profesor Ram Subramanyam chats with a 4th grade student about his project, "The R.O.V.E.R.".

Another side benefit was that parents wouldn’t have to facilitate their kid meeting another outside of school to work on their projects: working on websites would be easier for groups because they could do it from computers at home and wouldn’t have to meet up.

According to Bronowski, the main goal of their fair is to give students real-life experiences. “The way that it's designed,” she explains, “the conversations with the experts, all of that is to really kind of replicate the types of things that they would be doing in real life in careers in the STEM field.”

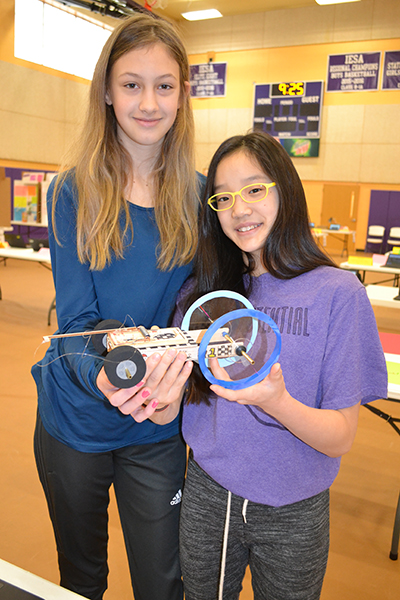

Two Next Generation students show off the prototype they built as part of their “Rodent Racers” project.

Another life-long skill the students gained through the fair was learning how to learn things on their own. She says the fair encouraged NGS students to explore a subject in which they’re interested in order to gain some in-depth knowledge about it.

“It gives them that experience of having a question, having a passion, and pursing that in a way that causes them to dig a little bit deeper. Because it's all individualized, and they can create their own path, they want to go a little bit deeper than they would in the context of a normal classroom.”

Another life-long skill students gained was communicating… especially talking to someone who might be a complete stranger to them.

“Having our experts come in and spend time with our students and talk to them, it gives them that experience too of meeting someone new and really having to explain from the ground up what they did. It builds a sense of community, but also the individual passion that they want to pursue.”

Integral to the fair, of course, was the 20 or so community experts, many from the university, who showed up to interact with the students about their projects, drawing upon their expertise in their various fields. After hearing the students’ presentation, asking questions, and/or making suggestions, the judges then sat down and filled out the rubric NGS has developed over the last several years. It doesn’t use points to assess students’ work, but allows experts to first affirm what students did well, then give them constructive input about what they can do better next time.

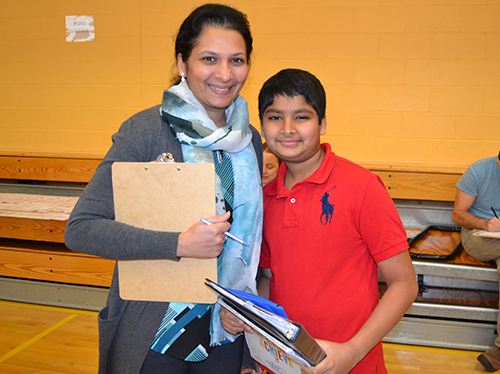

Professor Suprita Prasanth listens as a Next Generation student shares about her project.

Professor Suprita Prasanth listens as a Next Generation student shares about her project.Below: Prasanth and her son, who just might be following in mom's footsteps.

Why do these experts take time from their work to devote an entire morning to the fair? They believe it’s important. For instance, that’s why Supra Prasanth, from the Cell and Developmental Biology Department, served as a judge for the first time this year. An NGS parent, she’d been to the fair before to support her child, but had never served as a judge.

“I've been very excited about just seeing small children get into science,” she reports, regarding her experience. “I think that's really important…I really think that small children should be initiated early on into science, and NGS does a fantastic job about it.”

Since her NSF-funded research involves studying how genetic material, such as DNA, duplicates when cells divide, it’s not surprising that her son, a 6th grader, did a project about DNA—specifically, how it looks, as he isolated DNA from different berries. Even though her son’s project is in her field, it’s NGS policy that parents can’t judge their own kid’s project, probably so the parent doesn’t let their child off too easy when it comes to critiquing their work. However, according to Prasanth, she probably would have done the opposite had she evaluated her own child’s work, and raised the bar in terms of her expectations.

Was she tempted to take over his project, since his research was right up her alley?

“I totally was hands off,” she claims. “I took him to my lab, and he was able to do a lot of things, think about it, and I did give him a lot of freedom in term of thinking and execution. But when the results came out, we obviously had a lot of discussion of what it means.”

Stacie Nakamura, a new primary (K–5th grade) science teacher.

Also experiencing her first NGS fair was Stacie Nakamura, a new primary (K–5th grade) science teacher starting in 2018. Having now been involved with the entire process, she shares how rewarding it was to see the students through to completion.

“We've worked for the past month with the students on coming up with a question, and all the different aspects of the science and engineering steps. It's really cool to now be able to see them present to the experts, and now see just how much knowledge they are to gain from this.”

Nakamura, who completed her Bachelors in animal science and a Masters in Elementary Education, claims that Next Gen’s schedule, which has students doing science every day, is really unique to the school.

“Science just sparks so much curiosity with the students and something that they will need in the future with technology and engineering. So many of them want to do things with computers or things with building, and I think this serves as a great opportunity to start giving them that experience with seeing that this is all that goes into being a scientist.”

She adds that she’s happy to be at Next Gen because she loves science and getting to teach it every day. “I was so fortunate because science is something that I love learning about, and now I get the chance to teach and hopefully inspire passion in the students that I am with here.”

Another Science and Engineering Fair rookie was Jennifer Wick, a Public Programs Specialist at the Champaign County Forest Preserve District, who oversees environmentally-based public programs, including summer day camps. Her first year serving as a community expert, Wick agreed to participate because the fair sounded like, “a great way to interact with kids and hopefully give them some good feedback that can help them make improvements next year and show them that it's cool to be interested in this sort of thing.”

Bill Rose of Illinois' Applied Research Institute interacts with an NGS student presenting his research project, "Viscosity of Motor Oil in Different Temperatures.""

Her impression of the fair? “It's so impressive to see the thought that these kids have put into their experiments and their projects. It's really exciting to see, starting at this level, kids doing this type of thing. It makes for a really promising future.”

A fifth grade student with the balloon-powered car he built.

Another expert, Bill Rose from the Applied Research Institute, who does applied science and engineering research on buildings, shares why he participates in the fair every year. “I learn stuff!” he admits. He then goes on to marvel at the knowledge of a 5th grader whose project he’d assessed who was discussing the Clasius-clapeyron equation when explaining his project. (Here's a link if, like this reporter, you have no idea what that is: Chemistry Libretexts website.)

Another expert was Jeff Moore, whose work at Beckman Institute involves making materials that are used every day last longer. “We study self-healing polymers,” he explains, “materials that when they're damaged can trigger repair.”

Moore commends the school, saying that from the youngest to the oldest, NGS students are consistently taught the message of “This is what the scientific method should look like, and this is how it is thought about.” Regarding serving as a judge, he reports, “I saw great curiosity in some of the students to get that initial question started and then proceeding through to 'How can I design an experiment to test that?' and then come up with some data and conclusions.”

Moore acknowledges that he participated in the fair because he’s “interested in seeing the Next Gen students become the next generation of scientists.”

More: 6-8 Outreach, K-6 Outreach, Next Generation School, Science Fair, 2019

For additional I-STEM articles highlighting Next Generation School's partnership with the University of Illinois, see the following:

- Students Hone Their Research Skills, Learn From Experts at NGS's 2018 Science & Engineering Fair

- At NGS' Science & Engineering Fair 2017, Every Student Is a Winner!

- 2016 NGS Science & Engineering Fair Fosters Research/Presenting to Experts

- 2015 NGS Science & Engineering Fair Called the "Most Successful" Ever

- Next Generation School's Science and Engineering Fair: Every Student Is a Winner

- Next Generation School Fair: Tomorrow's Scientists & Engineers Meet Today's

- Local Teacher Uses Project Lead the Way to Prepare Next Generation of Engineers

- MechSE Gives Back to the Community

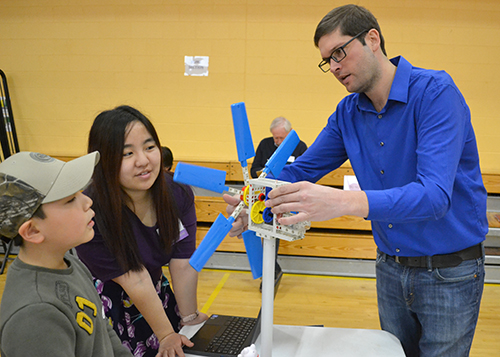

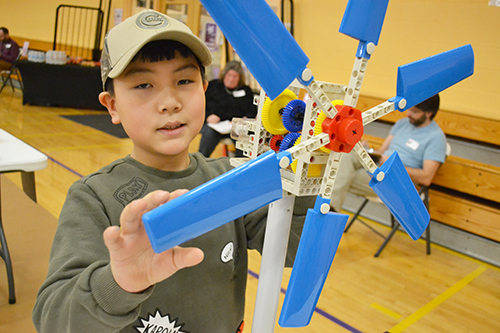

Next Generation School science teachers Stacie Nakamura (center) and Bryant Fritz (right) help a student trouble shoot his project.

With his windmill project working properly now, thanks to a little help from his teachers, the student is ready to present.

A team of students exhibit the mouse trap vehicle they made while presenting their project, called “Mouse Trapped."

.jpg)