Next Generation School's Science and Engineering Fair: Every Student Is a Winner

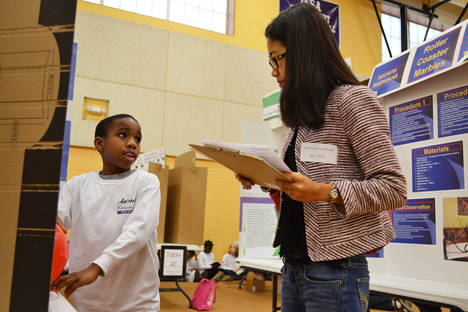

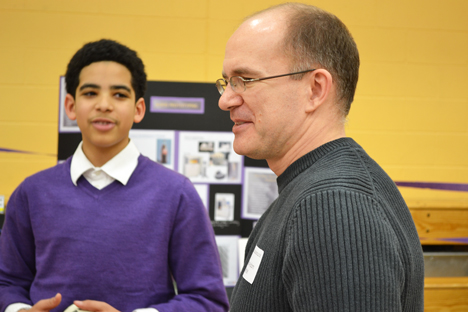

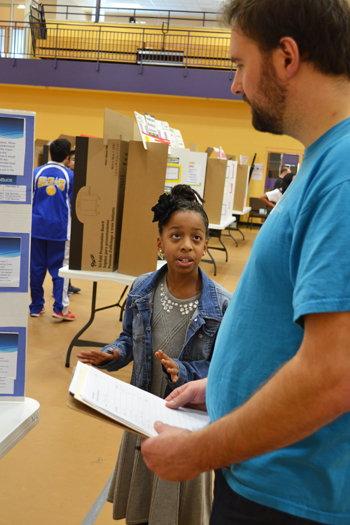

An NGS student presents her research project to Illinois Ph.D. student, Julia Ossler.

March 11, 2014

Compared to most science fairs, Next Generation School's Science and Engineering Fair is unique, in that no one student or team is designated the winner. After weeks researching and learning about a subject in depth, designing and conducting a research project, and finally making a poster presenting their results, during the February 21st fair, each student had the opportunity to present their research to a local expert for feedback—making all the students winners.

Carrie Kouadio, Education Coordinator for the Micro and Nanotechology Lab who also coordinates the science fair, says one of the benefits of the fair is how students gain an in-depth understanding of their topic—which often fosters interest in science.

"They spend six weeks very heavily devoted to their project. They get to deeply go into the content and the skills that are necessary to do that project, so they're really getting a deep understanding of whatever topic they choose. So I would say that deep involvement in science is very important for that understanding of content, but also to help motivate interest."

According to Kouadio, another benefit is that students "see the scope of science and engineering in general. So when they come to fair, they're seeing that there's this huge range of type of projects to do: everything from chemistry, physics, life science, engineering, psychology, computer science projects, and they see that there's something for everyone. There's something that almost everyone will find interesting."

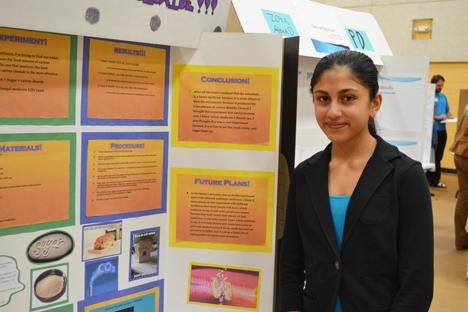

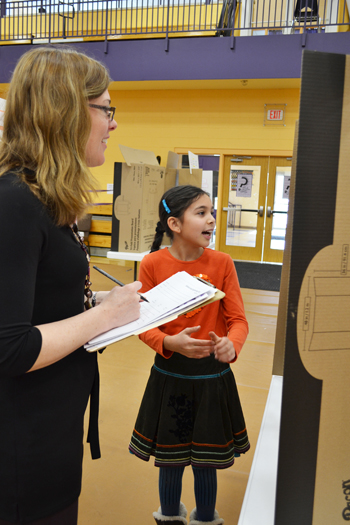

An NGS student waits to present her project about carbon dioxide released by antifungal medicines.

Kouadio believes the fair also builds students' self-esteem: "We really encourage ownership of their projects. So I think that helps to contribute to their self-esteem in knowing that they chose a project that they were interested in, and worked hard on it, and they have learned many things, and so this is helping them grow as an individual."

For NGS's primary science lab teacher, Kathy Feser, the science fair's benefit for students is not so much the science they learn, but the process they go through:

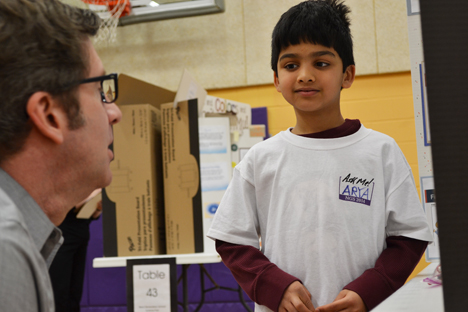

An NGS student disucsses his research project with Yi Lou, an Illinois Ph.D. student in Natural Resources and Environmental Science.

"I think it pushes kids to think about science in their own way. So my emphasis not on the science itself, but the process. So it's the one time, especially, that the younger students are asked to design their own projects, think about their procedure, make a list of the materials, do it, think about what the results are, and think about their conclusion."

Head of School Chris Bronowski agrees that one of the major benefits for students is the process: "That's a valuable process, whether you're investigating science or whether you're making a movie, or whatever it is. Going through that investigative process and pushing yourself into doing things that you did not think that you would be able to do is just a valuable life skill."

Ashley Kozak, co-teacher in the primary science lab, agrees that the process teaches students important life skills, such as perseverance. "As a science teacher, I love it. It's great to know that you've helped the students, and you've instilled something that they will know how to do, that being the science process, and actually getting them to finish tasks and to work on an agenda. And it helps them later on in life to know that if they have something that they are really excited about in their life, to pursue it."

According to one community expert who has been involved with the fair for several years, Chemistry Professor Don Decoste, another benefit of the fair is that students "learn that science is a verb instead of just a noun. They learn that in order to understand science, you have to do science."

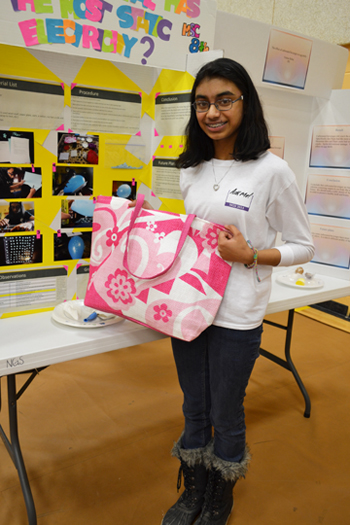

Meghana Muthekepalli displays the item that exhibited the least amount of static electricity during her testing.

And like Feser, Decoste believes exposure to the scientific method is another important benefit for students: "They understand that science is also not just about facts and things that you are just supposed to know, but it's about having a question, and it's about trying to answer that question."

For example, the question that NGS student Meghana Muthekepalli was trying to answer had to do with static electricity. "There are always a lot of static electricity shocks in the winter," reports the 8th-grader, "and I always got really annoyed with it; it hurt really bad, and so I was just wondering why it was happening so much." So she decided to research it for her project.

What did she learn? Water molecules in the air normally conduct electricity; but because there isn't much humidity in the air in the winter, the electricity goes through the air, causing static electricity. Her recommendations: use a humidifier, and wear certain kinds of clothing that don't conduct electricity, like silk or a wool sweater. Is the eighth grader an electrical engineer in the making? Possibly. Muthekepalli indicates she might like to do further research on what kind of wires/metals conduct electricity best.

Decoste goes on to describe what he sees as a further benefit: students experience some of the frustrations of research—when the results aren't what you'd hoped they would be: "It's hard to answer that question sometimes," he continues, "and sometimes you don't get a great answer. So I really think that's an important part of learning science."

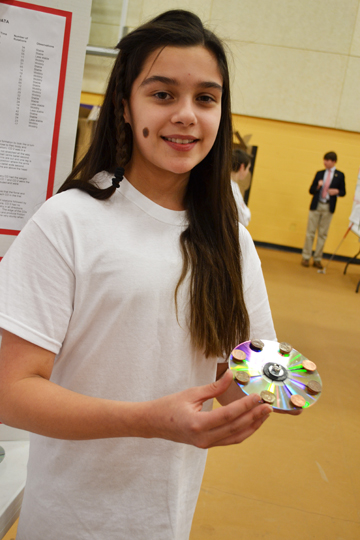

Maya Kesan displays the top that spun the longest during her testing.

For instance, the question that seventh grader Maya Kesan wanted to answer was related to her spins while dancing. "Well, I'm a dancer, and I was always fascinated by how my different arm positions affected the speed and how many rotations I did in a certain amount of time."

So her research project had to do with spinning tops and how the placement of pennies on them affected the number and speed of their rotations. Her thesis was that the top with the pennies placed closest to the center would spin the fastest "because whenever we turn, we always put our arms closer to the body."

What did she learn? Based on the data from her tests, she indicates that she learned about several physics principles: the conservation of angular momentum, torque, and "how you must overcome inertia to move or to stop moving." What else did she learn? "Well, I think it just helped broaden my view about spinning, and how there's a lot more going on than just spinning."

For Lia Dankowicz, a seventh grader who aspires to be a teacher, her project had to do with an interest of hers: the brain and how it works. "I really like psychology, so it was really nice to learn how it affects people because it was a lot of stuff I learned in this project that helped me more understand myself and what happens in my brain."

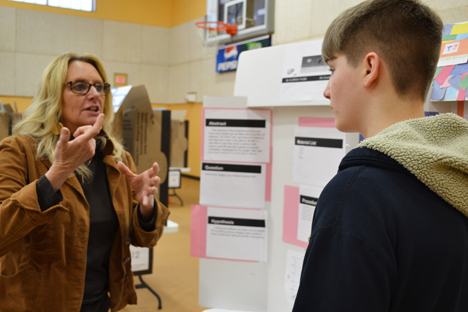

Another important component of NGS's fair is students presenting their work—first to community experts, then later in the day, to family members and the general public. "Presenting to someone is also an incredible skill to have," Bronowski explains, "and that is something that our school really fosters."

To provide a knowledgeable audience of experts to whom students could present their research, 20 local scientists, engineers, and educators were recruited to share their expertise with students. (Nineteen of the 20 work at Illinois; the one who doesn't, Orpheum Children's Science Museum Education Coordinator Rory Dushman, just graduated from Illinois in December.)

NGS seventh grader Lia Dankowicz explains her project on the psychological effect of colors to a community expert, Ph.D. student Yi Lou.

Why this emphasis on community experts? Coordinator Carrie Kouadio describes how using experts can add to students' learning experience.

"We are committed to having people who have expertise in some area of STEM, because when they're interacting with the students, they need to have that background knowledge of science and engineering, so that they can ask the kind of questions that the students need to be asked."

In addition to being asked the right questions, the goal is for students to have "a really full, complete experience of having someone who understands what they did and has even lots of outside knowledge that they can contribute," continues Kouadio. "They have experience perhaps in the area; they can suggest areas that are valid for future study; they can give tips on how to improve."

A student disucsses his project with Education Professor Adam Poetzel.

According to science teacher Feser, the kids—in awe of the experts—take what they say to heart. So, just as she as a teacher reinforces what parents say to their kids, the experts help to reinforce what she says.

"Anything that someone from the community will say to these children will stick more than what I would say…They can excite our kids and remind them of things that I have said over and over again. If this expert, who is spending time with them for 15 minutes, says it, they will remember it a lot longer." She cites the "fair test" principle she has evidently stressed over and over to her young charges: "'Change one variable at a time; make sure you measure, and write the right numbers down'—all these little ideas that you need in science. And if they say it, then it sticks longer."

Scott Robinson from the Beckman Imaging Technology Group, who is also involved with the Bugscope project, discusses an NGS student's project with him.

Experts, who come from a broad range of disciplines, were encouraged to choose projects related their expertise. Thus, it was often the case that experts could serve as a role model—someone who actually had a career in the area the student's project was in.

Julia Ossler, a Ph.D. student who studies microbial interactions in soil, reports hearing conversations where an expert would go up to a student and say, "Do you know why I chose your board? Because I study this for a living."

She goes on to share how this might cause a students' interest in the field to grow and become a viable career choice. "So they really see that it's not just a school project, that they can do what they've done here and keep pursuing it and make it into a career, a passion."

Ossler describes how she herself encouraged a student who did a project on bacteria. "He was so into it. He had all of these ideas, and he was just everything bacteria. And I was like 'Don't ever lose this passion, because you can do this for real.' Just that realization for them to see how we take these experiments, and we do things like this in the lab. But they don't ever get to see it unless you bring the experts in and show them that you can do this as well: 'Just keep pursuing this, and don't let go of this."

Bryant Fritz, NGS's middle school science teacher, also hopes students' interactions with experts could get them interested in STEM careers.

"I think it's a great experience just to have that conversation with the judges, because the kids are incredibly nervous going into it. Once they have this conversation, they realize, 'Oh my gosh, this person is really interested in my project, and they think what I'm doing as an 11- or 12-year-old student is really amazing.' This gives them confidence, and our goal with the fair is try to inspire this interest in STEM-related fields."

Psychology Professor Kara Federmeier evaluates an NGS student's presentation during the fair.

Head of School Bronowski adds that presenting their research to experts further exposes students to another aspect of a career in STEM—having one's research vetted by colleagues. "They get to really see what it's like to work as a true scientist or engineer. Because that's part of a scientist's or engineer's life, to present to colleagues, to gain feedback, to think about what steps you take next. And to get someone's opinion on if your work was really great or, 'Hmm, there may be some flaws here that you really need to think about."

Psychology Professor Kara Federmeier, whose research area is cognitive neuroscience, agrees that a youngster's early experience presenting to the public is an important skill they may need later in life: "I get graduate students who have never had the opportunity to present science to a general audience and, even at that stage, there's a lot of learning to do about, 'How do you make your project accessible to other people? How do you talk to people about what you're doing and explain it?' So to be able to do this when you're a grade school kid and have that kind of experience going forward, I think it demystifies the process, and it also shows them the kind of professional skills that they would need."

Science Educator Anita Martin interacts with a student about his project.

Science educator and and EnLiST Project Coordinator Anita Martin also believes that the composition of the team of experts, in terms of its gender and cultural diversity, could positively impact under-represented students to choose STEM fields.

"Any time they have the opportunity to see the whole STEM pipeline, I think it's important, but specifically for women and minorities. I think for all cultures to be present at this event is very, very important. I think that every time there's a situation where they see cultural diversity and gender equity, that really changes whether they think they can be in STEM or not."

Chemistry Professor Don Decoste discusses a student's project with her during the fair.

While judging the fair takes several hours out of community experts' busy schedules, they see it as well worth the time. For instance, Chemistry Professor Don Decoste, who has served as a judge for a number of years, says: "I really like to see what kids are doing with science. I like to talk with them about that. I am always interested in what they can come up with and how they approach a problem. So after doing this the first time, I really enjoyed it and just like being part of it."

Participating in the fair for the first time, Julia Ossler was pleasantly surprised by the way students embraced feedback: "I love the integration of the experts with the kids and giving them critical feedback at such a young age. And their responsiveness to it is surprising. In the conversations that I've had with students already, I give them a critique about design and extra thoughts, and they reply'Absolutely!' which I did not expect."

Devoting even more time to the fair were the Next Generation teachers, such as Bryant Fritz, who enjoys watching kids become more interested in science as they succeed:

A student presents her research on hamsters to Simon Pearish, a Ph.D. student in Ecology, Evolution, and Conservation Biology.

"I think the really rewarding part about teaching the whole process is when you have those kids that are struggling with figuring out what they are doing. When you give them help with what they are doing really well, and what they can improve upon, and they get excited when the results are changing, and they are being a little more successful. Now, they are getting more interested in the project and liking it a lot more. That's a really great moment as a teacher when you can get the kid more interested and inspired to perform better."

Fair coordinator Carrie Kouadio has been involved with the fair since its inception, when she was a teacher at NGS, enjoys the way it has developed over the years. "I been involved from the beginning, and I like to see how things progress, and I like to contribute to the progression of the fair."

Kouadio shares an anecdote about how the fair fosters students' interest in science: "Parents tell me stories about their kids who they think didn't have a particular interest in science but because we really encourage them to choose something they find really interesting then they get to focus on that for a while and they see that, 'This is fun, and I want to do this more.' They are asking to do more projects at home that are in the same vein as what they have done. So we really just want to help children find that area that is really interesting and motivating to them and encourage them to continue that. That's a lot of what the fair is about—motivating and inspiring this love of/interest in science."

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: 6-8 Outreach, K-6 Outreach, Next Generation School, Science Fair, 2014

For further information regarding Next Generation School's partnership with the University of Illinois, see these additional I-STEM articles:

- 2016 NGS Science & Engineering Fair Fosters to Research/Presenting to Experts

- Next Generation School Fair: Tomorrow's Scientists & Engineers Meet Today's.

- BTW Kindergarteners Have a Ball Learning About Polymers, Manufacturing.

- Local Teacher Uses Project Lead the Way to Prepare Next Generation of Engineers;

- MechSE Gives Back to the Community.

An NGS student and Anne Erdmann from the Illinois State Geological Survey interact during the student's presentation.

.jpg)