CEE Undergraduate Education: Shaping Multi-Disciplinary Problem Solvers

CEE 398 student on a tour of the University's Abbott Power Plant.

August 19, 2014

"Our agenda is to educate and help develop the next generation of civil engineers so that they are not only theoretically rigorously strong, but can also tackle big multidisciplinary issues in a way that they have deep understanding and are also capable of working with people from different disciplines to solve societal challenges." Liang Liu

Civil and Environmental Engineering (CEE) at Illinois is awfully good. But the fact that both the undergraduate and graduate programs are currently ranked #1 in the nation doesn't mean the folks at CEE are content to rest on their laurels.

In fact, Liang Liu, Associate Head and Director of Undergraduate Studies and Professor Jeffery Roesler, creator of the department's cutting-edge CEE 398 course, are working to reform the department's already-good undergraduate education and make it even better.

"From what I have heard from our peers," says Liu, "we offer the most comprehensive and rigorous undergraduate curriculum…At the same time, we are also looking for opportunities to enhance the rigor in theoretical and problem-solving skills...ways that we can enhance the learning experiences for our undergraduate students."

Liang Liu, CEE Associate Head and Director of Undergraduate Programs

One way to improve what Liu labels "the Illinois experience" is to add a project component beginning in the sophomore year to complement courses that teach theory. They envision a revamped suite of 200-level courses (201, 202, and 203); the course sequence would not only expose student to civil engineering domain problems and potential careers, but give them some hands-on opportunities as well.

"At the 200 level we have a connection to help students better understand, with hands-on experience, the kind of domain that they can get into," explains Liu, "and they can select their career choices by a deeper understanding of the domain issues. So while they are learning about the 200-level theoretical components or modules, they also have the parallel project base (203) that they can get their hands on."

The prototype which models many changes these visionaries hope to incorporate into 203 is CEE 398 PBL (Project-Based Learning), a sustainability course first offered in Fall 2013. By incorporating civil engineering projects into the program, Liu expects the project to serve as "an inspiring mechanism or tool."

Unique aspects of the course include field trips to campus sites currently grappling with sustainability issues. Another facet of the course involves a multi-disciplinary emphasis: since engineers often work to solve inter-disciplinary problems, students are exposed to faculty with diverse specializations, and the problems they address are multi-disciplinary in nature. The pièce de résistance of the course is a project—students working in teams to tackle real-world, campus problems.

According to Roesler, for Fall 2013 CEE 398 students found the field trips to be one of the most important aspects of the class. "Many of these students don't know what civil engineers do, and therefore them seeing something in action that was done by a civil engineer gives them a really good idea of what life as a civil engineer may look like."

The goal in emphasizing actual campus sustainability issues is to tap into students' desire to make a difference.

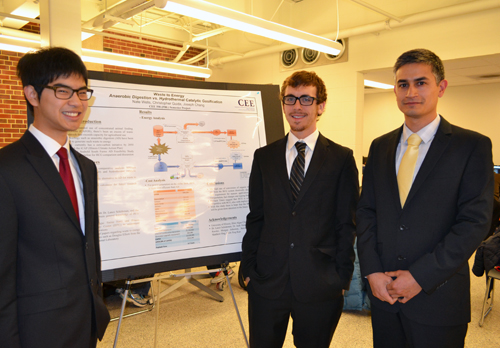

The team of CEE 398 students who worked on the Anerobic Digestion project.

"We are looking into ways to help students discover their interests and inspiration by addressing the bigger goal of serving societal needs," indicates Liu, "because very likely, students may learn solutions, not only on the engineering side, but also on the social issues and the sustainability issues."

Jeffery Roesler, CEE Professor and Co-creator of CEE 398 PBL.

Roesler agrees, indicating that most students choose engineering because they want to help people.

"A lot of students have a passion to solve problems," suggests Roesler, "and this class will motivate our students. Because for most of them, that's why they got into engineering. They didn't get into engineering just to do homework sets; they want to feel like they are solving a big problem."

However, one glitch encountered during the course's pilot run was reigning students in—in their zeal, they wanted to solve one of the world's major problems...all in one semester. Roesler says he often had to temper their enthusiasm:

"Well, it's nice to save the world, but let's save it over four years and not one semester."

Then he would outline a strategy: take another class about the topic; submit a proposal to the campus sustainability committee; take Engineering 298 (Heroic Systems: Technology and Culture); do undergraduate research with a professor also interested in this topic. "So give students an idea that this is not the end," he adds. "This just begins the discovery of the topic you are interested in."

In addition to acting as a lure to reel in and engage students, this emphasis on sustainability is also important because it is integral to the department's mission. CEE is no longer our father's Civil Engineering Department. The stereotype about civil engineering held by the man on the street—that it's only about building structures—no longer holds true. CEE has undergone a metamorphosis over the last few decades to also embrace the environmental impact of that structure. According to Liu, CEE students now need to know more than just about how to build a bridge or a dam.

"If you build a dam," Liu qualifies, "you're going to have some impact on the environment. They also need to understand some sustainability issues to get them a little bit of understanding of the domain."

Committed to the pedagogy of STEM education, Liu is intrigued by the learning process students go through. He calls the process of learning and discovery in CEE 398 "inspiring."

CEE 398 students examine the smoke stacks during the power plant tour.

"It will also consolidate the theories they learn and it is mutually beneficial. You trigger the curiosity and you learn more theories and that will be kind of self-motivating in a way in terms of pedagogical approach."

What Liu believes to be one of the strengths of CEE 398 is that the course's unique process of learning will help their students become problem solvers. Why is it important students learn fundamental problem solving skills?

"Because we cannot teach them what they need to know in the next forty years," admits Liu.

"So students will be involved in framing the problem solving instead of a set-up solution where they go A, B, C, and D and find a solution. They will be able to define, ‘How do you frame a problem? How do you define the issues? How do you look into the process of finding that solution?"

Liu also wants CEE students to be dauntless—problem solvers who aren't afraid to take some risks: "At this stage," adds Liu, "it is very important for them to be bold; be daring; be willing to fail."

Roesler agrees with the idea of fostering risk-taking among the students. "I was very apprehensive about a year ago when I talked to Liang and he says, ‘Go do this course.' And I was like, ‘This could be a disaster!' But I was doing exactly what I want the students to do. I said, ‘I am not sure where this is going, but I am going to take a risk.' So I put a lot of effort into it, and I think it paralleled what we want our students to do. See an opportunity. Take a risk. The students here are very smart and we want to lead the world in producing good civil engineering students, so we want them to be on the forefront on solving big problems and leading big teams."

Two Civil & Environmental Engineering students during a site visit to the university's power plant.

Thus, helping students become comfortable working on interdisciplinary teams—just like real engineers do—is another goal of the course. So team projects, plus exposure to faculty from various disciplines, were included in the course "so students see that problem solving is not only one single area. It requires a team of experts collaborating together."

"So this particular issue that we're looking at could be a civil engineering problem," says Liu. It could be a sustainability issue, but it is going to pull people and expertise from all areas around campus. Students get to see the value of that, and they learn to approach the problem from different angles to be able to define a problem in a more realistic way. This is something a more theoretical-based curriculum could not provide in the past."

Liu has dubbed the course as "cross-cutting," partly because they have recruited multidisciplinary faculty and engineers from across campus to help teach the course.

"So instead of one faculty member with his or her strengths, we're aiming for a synergy of different faculty/experts with their different emphases. For example, a student might choose a problem that might be beyond the scope of any one faculty member."

"That's right," agrees Roesler. "I do not have the solutions for every project. Even the domain knowledge. I think one of the things that I've learned in the last year which is important, is that as we move to the 21st Century engineer, they need to be able to solve complex problems on big teams. We don't only have, ‘Well, we need to build a bridge across the river.' Those challenges are still there, but they're not the only challenges."

Roesler also applies the "cross-cutting" term to the projects class, which forces students to glean theory from the different courses they've taken.

Abbott Power Plant Engineer Mike Larson (left) explains to CEE 398 students some campus sustainability issues they deal with every day.

"I think one example is," explains Roesler, "the project class allows you to gather your own set of data for whatever topic it is, whether it's measuring building climate, temperatures, air flow, or traffic; the other classes give you technical content to analyze that information. So they cross in that the concepts to analyze data in terms of statistics, in terms of planning large-scale systems are taught in different classes, but this class applies that information to a real set of data. It makes it real for the student, not just a bunch of numbers we make up to show how to average numbers or whatnot."

Not only do Liu and Roesler hope to acclimate students to working on teams; they hope to introduce this new pedagogical renovation as they foster working on teams among the Civil Engineering faculty as well.

According to Roesler, they intend to challenge the staus quo: one professor teaching one course.

"The traditional teaching environment is professors take care of their own classes and create their own content. And in order to effectively teach these types of courses that are large every semester, the culture of teaching as a team has to occur in Civil…it can't be one faculty member's job to carry a large course until he dies. And that's traditionally what's happened, and you tend to not get other people involved."

How do they intend to change this trend? How will they changes being made in the 200-level courses bleed over into the upper level courses? They believe it will just happen naturally.

Roesler cites his own experience with CEE 398 as an example of how team teaching has already impacted the way he teaches his other courses.

"I said, ‘Wow, I could really do my senior class much better.'"

So he changed his senior-level design course in hydro systems transportation. He integrated with another class, and they did a group project together, focusing on the project much more than previously.

CEE 398 students Ferisca Putri and Kathleen Hawkins explain their project to visitors to the course's final poster session.

"That would have never happened without this collaboration that I have with the other faculty members. We thought, ‘Well, we learned a lot here; let's just do it in another class; make it a lot easier on us; make it better for the students.' So I think some of the changes in the upper level class will happen maybe naturally as faculty understand some new things about projects and how they can be integrated into classes."

Roesler and Liu admit that CEE "borrowed" this idea of team teaching from Physics, which uses several faculty members to teach their large, introductory freshman classes.

"They spread the load out," admits Roesler, "and it makes it easier."

Roesler acknowledges that part of this whole reform process is learning how to mentor faculty to teach.

"When you bring faculty into the course, you don't say, ‘Take over the course. We'll see you next semester.' You bring them in and give them a little part to do."

In 398, some faculty do a case study—one lecture and that's it. Other faculty mentor a project team. That's all they do.

"So they get the idea of what the course is doing, but they're not responsible for the whole course."

Liu believes that once the faculty experience this innovation in instruction, they'll find it more fulfilling than the old way of doing things.

"Teaching must be a very naturally formed organic process so we are not complete without each other's contribution. This kind of contribution and willingness to share and the synergy that comes with this process creates a much richer content that individually could be achieved in his/her course. So that makes it more interesting to the student and a more dynamic curriculum."

What is Liu's role in this reform? "My role as administrator is to remove the barriers, remove the uncertainties, find the resources to support the faculty's creativity, and at the same time be understanding in terms of curriculum design so that we can provide students with the inspiration, with the opportunities to learn. Only with that we can see students flourish in an environment where the professor is excited. They are not forced to teach a course they don't want to teach, and they are inspired to teach things they believe will be critical to our students. That will be a beautiful result as an administrator."

Note: CEE 398 PBL still has some openings for students for Fall 2014. Students do not have to be civil engineers, or even engineers, to take the class.

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Civil Engineering, Environmental Engineering, Undergrad Education Reform, 2014

For more on CEE 398 PBL, see the followingI-STEM articles and the video about the class produced by the CITES Video Group:

- SIIP: Reforming Undergraduate Engineering to Engage Students

- Students in New Sustainability Course Tackle Real-World, Campus Problems

- CEE 398 Project-Based Learning Promotional Video

CEE 398 students during a tour of Abbott Power Plant.

.jpg)