4H STEM Specialist Keith Jacobs Shares His Passion for Technology With Illinois Youth

“This is a pretty cool job because all the things I would be doing at home anyway, I do here, and I get paid to do it!” – Keith Jacobs

Feburary 6, 2019

4-H STEM Specialist Keith Jacobs.

4-H STEM Specialist Keith Jacobs.

One of Jacobs' toys, a DJI Inspire 2 drone.

Entrenched in front of a newly-acquired, huge flat-screen tv that serves as his computer monitor, and surrounded by his tech toys—myriad boxes of cutting-edge technology including drones, virtual reality headsets, Makey Makey kits, and 3D printers courtesy of Google, Microsoft, and other tech giants— Illinois 4-H STEM Specialist Keith Jacobs imparts his tech savvy to youth all over the state. In his free time, he’s developing drones to provide medical services to folks in remote areas. And while these two passions might seem to be totally unrelated, they’re really quite interconnected.

For instance, when Jacobs was in college, he couldn’t quite decide what he wanted to do careerwise. So he dabbled in this and that, studying several seemingly disparate fields, which actually contributed to his getting to where he is today. After taking a rather round-about route, he’s presently doing two things he’s quite passionate about—developing medical drones and educating young people about STEM.

Jacobs started out seeking a dual degree in aerospace engineering and physics during which he realized he “hated math...but was really good at it!” So instead of doing that, he decided, “I’ll do medicine. That’s like…no math!”

So he switched to Psychology, pre-med in Neuroscience, where, ironically, he discovered, “Oh, man, there’s so much math! It’s all math too!” But by that time, he figured it was too late to change, so he “just dug in and did it.”

Bachelor’s degree in hand, he headed to medical school. However, it wasn’t long before he discovered, “This isn’t the only thing that I want to be doing for the rest of my life.” So he left medical school.

That’s when his interest in aviation—specifically drones—once again took center stage. He had an epiphany, and realized that his dream job incorporated a couple of his previous interests: “Well, I want to build drones for medical purposes and start a company,” he decided.

However, when drones first started gaining popularity around 2013, one couldn't just run out and buy one. “The first drone I had, I had to build it,” he confesses. So he taught himself how to build one—a habit he's found extremely helpful in his current career at 4H.

Jacobs takes his DJI Inspire 2 drone for a spin outside the Illinois Extension office.

Jacobs takes his DJI Inspire 2 drone for a spin outside the Illinois Extension office.

Upon hearing about his plans, his parents freaked out. “What are you doing? You're not an engineer. How are you going to do it?” He told them, “I'll figure it out.” And he did.

However, at that point he also realized that people might not take him seriously regarding his dream job—medical purpose drones—and might accuse him of not being qualified. “You're just some guy that started building drones!” they might say. So he got qualified. He went back to school and got a Master's in Public Health and grad certifications in public health and environmental health, specifically epidemiology.

While similar to his original goal of medicine, he claims that public health differs in that “On a large scale, medicine is like the individual level, one patient at a time, versus public health, which is the overarching view of medicine, so reaching populations and specifically epidemiology. I got certifications in epidemiology, and emergency preparedness, and homeland security, so that I can integrate these into medical purpose drones.”

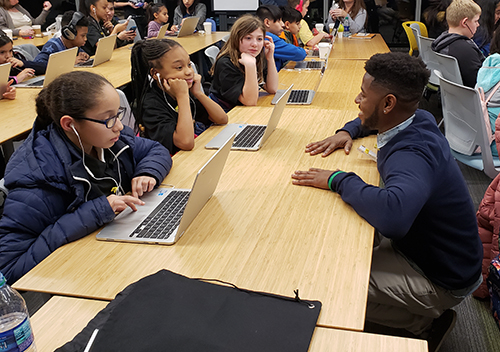

Jacobs interacts with Chicago youth about technology during the Google event he helped run. (Image courtesy of Keith Jacobs.)

Jacobs interacts with Chicago youth about technology during the Google event he helped run. (Image courtesy of Keith Jacobs.)At the time he decided to explore this area, most people were envisioning drones that did medical drop offs and deliveries in remote areas. But he said to himself, “Okay, I don't want to be in the weeds with them. I want to be doing stuff beyond that.” So he developed what he calls a telemedi (telemedicine) drone. “It can land in front of you and connect you to a doctor,” Jacobs explains. “The doctor can do a history, physical exam on you from anywhere in the world and be able to diagnose you right on the spot.”

His plan is to use ultra-high-frequency microwaves to connect people long distance. Originally, he intended that his drone would mostly be used in third-world countries, but now he qualifies that it could be used for both medical delivery as well as connectivity in rural areas anywhere in the world.

Corroborating the need for such a drone, the Ebola crisis had just hit in West Africa when he was dreaming up the type of drone he wanted to develop. He recalls that because there weren’t enough doctors present, officials weren't able to ID patient zero, thus allowing Ebola to spread.

“With a solution like this,” he explains, touting his medical-purpose drone, “you can put boots on the ground without having to have any doctors in that area.”

Although he’s recently designed a medical delivery drone, a telemedicine drone is still his dream: “I've published on it. I've done a lot of different things on it, and that is where my big dream is really at.”

Jacobs pilots the DJI Inspire 2 drone, using an ipad to view the birds-eye images from the camera mounted on the drone.

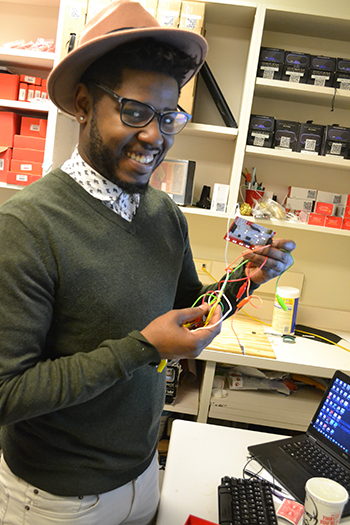

Jacobs pilots the DJI Inspire 2 drone, using an ipad to view the birds-eye images from the camera mounted on the drone. Keith Jacobs shows off one of the numerous Makey Makey kits he has available.

Keith Jacobs shows off one of the numerous Makey Makey kits he has available. But in the meantime, isn’t Jacobs' stint as 4H STEM Specialist taking him on a major detour from his big dream—telemedi drones? Not really. Here’s why.

Jacob’s passion for STEM education began when he started passing on to kids some of the technology he’d taught himself. For instance, besides teaching himself how to build a drone, he learned how to build a 3D printer. For both, he says he had to learn “a whole new set of skills.” That’s when he realized he had something today’s young people need.

“I was like ‘Man, I can do all this robotics and coding, and I taught myself how to do these things using YouTube and searching the internet,’” he explains, adding that, “Kids need to learn how to do this because they can get whole jobs doing this stuff without necessarily having to go to college first. But they can start learning this stuff now!”

So he started working with kids. One thing led to another, and he ended up at the 4H state fair judging rockets. The experience changed his perception of what 4H was and its potential for STEM education.

“Somebody was like, ‘Oh, you know all these things. You know about all these things, but you don't know about 4H?’” he recalls. “I'm like, ‘No, I don't!’ I just saw a bunch of people hitting pigs with sticks and all this stuff I wasn't used to. I had never been around it or anything.”

That was when a current colleague recommended, “Man, you should totally apply for that STEM job. There's a job that just opened. It's a STEM specialist job.” Deciding that was what he wanted to do, he applied and got the job. “And now I get to do a bunch of cool stuff!” he boasts.

One of the cool things he gets to do is to ensure that Illinois youth are exposed to cutting-edge technology like—you guessed it—drones. “So all of these boxes over here are drones,” he braggs, regarding his space, which is more high-tech gadget storeroom than office. “I have bigger drones in my car, drones and giant drones, small drones.” Then he excitedly shares about his current brainchild: “So I'm building out a curriculum now…It will be a curriculum that teaches kids how to build, fly, and race drones!”

For Jacobs, writing curricula has flowed quite naturally out of teaching himself how to do things. For instance, when learning how to build drones, he would write himself notes on how to do it, because it was “stuff that nobody was doing yet, and I needed to know how to do it and document it.” For Jacobs, it’s been a simple matter of recording how to teach others to do what he’s taught himself to do.

Writing new curricula is just part of the leadership he provides for 4H STEM programming throughout Illinois. He also writes grant proposals in order to purchase different types of technology. He shares how it works. The National 4H Council gets an invitation from a company then tells the states how much money is being offering. Jacobs then writes a grant on behalf of Illinois’ 4H clubs. Finally, the Council chooses which states get to participate. “Then we get the congratulations and then we start spending the money to get the stuff out there!” he finishes.

Of course, sharing the new technology is the fun part. One technology Jacob's acquired are Makey Makey invention kits—arduino-based computer chips, similar to Nintendo controllers, that use alligator clips to connect conductive things like Play-Doh and/or aluminum foil, to a computer, which can then be used to do coding and programming. Another technology his office supports is Scratch. Via a University of Illinois-developed curriculum about programming, kids learn how to create video games using the block-based coding language.

Google Expedition kit (Image courtesy of BestBuy.com.)

Keith Jacobs works with Chicago youth at the Google event. (Image courtesy of Keith Jacobs.)

Another technology Jacobs is excited about sharing is virtual reality. Courtesy of a 1.5 million dollar grant from Google, his office received Google Expedition Kits that go out to almost every STEM event in the state. Using the kit’s virtual reality headset, kids can download expeditions—3D virtual reality field trips—related to pretty much any topic. For example, youngsters interested in the human body can “tour” a human cardiovascular system. “The cool thing about these guys,” he explains, regarding the kits, “is that they all connect to a tablet where, if I'm giving a presentation, I can lead a tour and have everyone look at the same thing or provide arrows and everyone sees it at the same time.”

Plus, as a result of 4H’s partnership with Google, in addition to spending some of the company’s money for technology, he’s been able to rub shoulders with folks from the internet powerhouse.

For example, Jacobs and 4H’s STEM infrastructure appear to be a favorite go-to guy when high-tech corporations like Google want to interact with kids. “We made a lot of connections and relationships over there,” Jacobs says regarding networking with folks in Google’s Chicago headquarters. They’ll ask, “Hey, can you get 50 kids from Chicago together to do our code?” Then Jacobs and his educators supply the kids. In fact, Google recently asked Illinois’ 4H STEM team to be their sponsored organization at their volunteer week. “We got to go out there and really connect our youth with this huge company, and the Google headquarters is amazing. It's like an amusement park,” he claims.

Also, because of the Illinois program’s size and strong STEM activities, Jacobs and his team were asked to host the announcement of the 4H-Google partnership, which featured Google executives as well as the governor and was held at the Illinois State Fair. As lead on that grant, Jacobs and his team provided training to folks from the different states involved with the grant.

Regarding their reciprocal partnership with Google, he says, “They have a problem reaching youth, because they're a bunch of computer guys. They're like “We have this cool stuff. You know about the stuff, and you know about the kids, so can you maybe help bridge that gap?”

Close on the heels of acquiring new technology comes another of Jacob’s duties: training educators and program coordinators from the state’s 27 4H units to confidently go into the community to do the high-tech programming with youth. So he provides educators in the field training emphasizing the specific computer technologies cited above, such as how to use Scratch.

“Building capacity is the biggest need,” he explains, adding that one of the main challenges he’s faces is helping educators and program coordinators overcome their fear of breaking the technology.“Because I could bring in all these cool toys…A lot of them are afraid they’re going to break it. Once you get to the point where you're trying to break it, then you'll learn it. That's been one of the bigger challenges, I think. But hopefully, we're going to have that solved with another grant that we just got to help combat that.”

While 4H’s STEM focus is growing rapidly, the organization still has traditional community clubs where students can choose a project, such as sewing, or baking, or horses, (or hitting a pig with a stick, as Jacob surmised), then exhibit at the state fair in hopes of winning a blue ribbon. However, 4H members can also choose from an ever-growing list of STEM-related project areas. In fact, Jacobs says these have grown so rapidly that they’re still developing curriculum for them, such as his Drones curriculum.

Jacobs peers through the telescope 4H purchased for the solar eclipse event. Illinois youth also use it to study the night sky during summer 4H camps.

In addition, 4H also has something called special interest or SPIN clubs. One of the biggies is the Robotics SPIN club, with from 500 to 650 kids competing in its end-of-the-year competition, scheduled for Saturday, May 11th, 2019, in Bloomington, Illinois. Jacobs and his Robotics Design Committee, comprised of youth formerly in robotics who now want to take a leadership role, will come up with the challenge. For example, last year’s theme was envirobots (environmental health-related robots). Teams of 3–10 kids choose from 15 different tasks, then will have from January through May 11th to program their robot to autonomously accomplish those tasks on a 4 by 8 foot mat within a three-minute time-frame. Teams have three tries to have the robot do the tasks.

4H also holds other large, state-wide events. For last year’s solar eclipse, 4H rented a minor league stadium, then projected images of the eclipse from a telescope onto the jumbotron. The 2000 participating kids and their families not only saw the eclipse, but got to do a variety of STEM activities, including virtual reality, robotics, and computer science. Jacobs and his team also do similar events in the inner city. For instance, Cook County youth are involved with robotics funded by a huge 4H grant specifically for robotics.

While Jacobs has little formal training in teaching, he’s honed his skills over the years. For instance, in college, he taught science at a school for kids with cerebral palsy and neuromuscular diseases. And he’s worked with medical schools to provide summer educational sessions for youth who want to be doctors, for which he’s received a lot of training. Plus, he’s been doing community outreach for a very long time.

Jacobs shares his STEM Education philosophy: “I like to be hands-on. I like to make it cool and fun. A lot of problems in programs are that they aren't cool enough. A lot of people are afraid to meet youth where they're at, so they want to say, ‘No, this is how you should be doing it!’ versus going to where they're at.”

His strategy is to meet kids at their level and use that to spark their interest in other things. “I like to say, sometimes I'm able to fool kids into liking computer science or drones or whatever.”

So is there ever a point where Jacobs will leave 4H to solely concentrate on his medical-purpose drones? Probably not. “This is long-term," Jacobs says. "I'll be here for a long time, because I like teaching youth.”

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative

More: 4-H, K-12 Outreach, STEM Pipeline, 2019

For more information about 4-H STEM programming, see these additional I-STEM webarticles:

- 4-H Robotics: Working to Make a STEM Career Down the Line Automatic

- 4-H Exposes Youth to STEM Via Informal Education.

Two contestants compete in a recent 4-H Robotics Competition.

Two contestants compete in a recent 4-H Robotics Competition. Jacobs exhibits another of his toys, a Tarot X6 drone.

Jacobs exhibits another of his toys, a Tarot X6 drone. Jacobs takes his DJI Inspire 2 drone for a spin outside the Illinois Extension office.

Jacobs takes his DJI Inspire 2 drone for a spin outside the Illinois Extension office.

.jpg)