Rodriguez-Otero Says SROP Puts a Face With an Application, Fosters Relationships

November 10, 2015

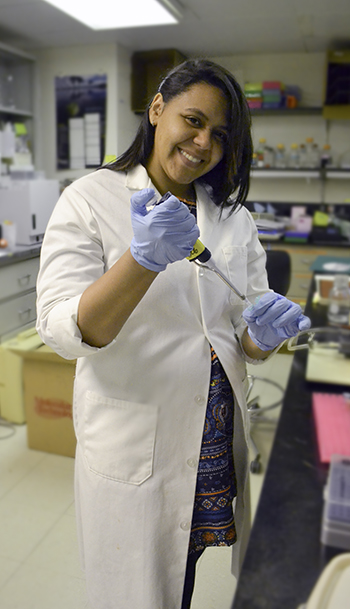

MCB graduate student Jannette Rodriguez-Otero in her lab in Morrill Hall.

So how did Molecular and Cellular Biology (MCB) grad student Jannette Rodriguez-Otero from San Juan, Puerto Rico, go from studying to be a barber in a local vocational school to working on a Ph.D. in molecular sciences in MCB's Cellular Developmental Biology Department? She claims that there’s one reason she’s at Illinois: SROP.

“If I wouldn’t have participated in the SROP, I wouldn’t be here right now, I think,” she explains. “Because the people wouldn’t get to know me, and they wouldn’t know how I work, because I got a recommendation from my mentor for the SROP. I think the SROP gave me a really big opportunity to get into grad school.”

The Summer Research Opportunities Program (SROP), one of a suite of programs in the Graduate College’s Educational Equity Programs Office that recruit under-represented students helped Rodriguez “understand the process about grad school.” She discovered that being in a summer program, being in research, and even more importantly, getting to know people would actually help her get into grad school.

“Sometimes we think, ‘Ok, I just send an application, and that’s it.’ You have to get to know people. You have to make a paper become a face. They have to know who you are.”

Rodriguez-Otero’s first step on her way to Illinois was to dream bigger…to choose a career in science.

“It was actually a change,” she recalls, “to decide, ‘Ok, I’m going to university.’

And everybody’s like, ‘Ok. Are you sure? You’re going to be a barber.’

I was like, ‘Yeah, I’m going to university, and I’m going to study science.’

She recalls that she was working in a barber shop at the time. Her uncle was the owner, and his response was, “Science? Really?” I told him, ‘Yes, I’m going to study science.” He was like, ‘Ok. I’m proud of you. Go ahead! Do whatever you have to do. Just don’t come back here!’” Laughing, she recalls, “I was like, ‘Ok, I’m fired then!’”

Rodriguez appreciates her family’s support once she made her decision. “They have been there since day one, since I said, ‘I’m going to study science.’ They were, ‘Okay. Isn’t that hard?’ I was like, “Maybe, we don’t know; we’ll see.”

Is it hard?

“No. It’s not that bad,” she admits. “If you really like it, you’re not going to see it as hard. There are some things that are not going to be easy, but that doesn’t mean it’s hard. It’s like everything, actually.”

Jannette Rodriguez-Otero (third from the right in the second row) at the 2013 Illinois Partners for Diversity Summit at Illinois (photograph courtesy of the Graduate College website).

Rodriguez-Otero actually visited Illinois once before coming here for her SROP. Along with her first research opportunity at UNE (Universidad del Este) in Puerto Rico, as a participant of the URGREAT-MBRS-RISE program, she visited other universities, including Illinois. The PI, Dr. Lilliam Lizardi-Oneill, who wanted her to come to Illinois for SROP the following summer, had her young protégé tag along to the 2013 Illinois Partners for Diversity Summit (another Grad College program whose goal is to establish relationships with Minority-Serving Institutions).

MCB graduate student Jannette Rodriguez-Otero (center) with her SROP mentors, researcher David Forsthoefel (left) and MCB Professor Phillip Newmark.

“We came to get to know the university,” Rodriguez explains. “We also got to know Daniel and Ave” (Daniel Wong, Associate Director, and Ave Alvarado, Director of Educational Equity Programs). “It was a fun opportunity. It was a little bit cold,” she admits. “We didn’t know it was going to be like that!” Despite the cold, this was probably when she started warming up to Illinois.

The following summer was her watershed experience in SROP. In addition to investigating regeneration of tissue with researcher Phillip Newmark, discovering what grad school is like, and networking, Rodriguez also made some lasting friends.

“When you meet people during the summer, you actually create really strong connections. It doesn’t matter if we’re not here [studying together at Illinois.] I still have communication with some of the SROP from my year.”

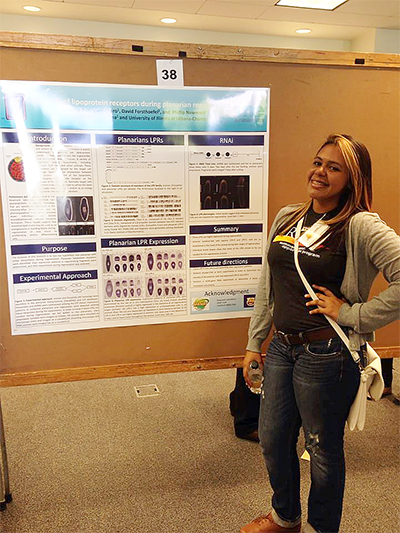

Jannette Rodriguez-Otero presents her research poster during the 2014 Undergraduate Summer Research Symposium.

Forming a bond with other students in one's cohort, like Rodriguez-Otero did, is key to the SROP experience. According to Wong, coordinator of SROP, networking/relationship building with other students in the cohort is an important component in not only SROP, but in all of his office’s programs.

“The cohort model is our default model because we find that to be successful. So that’s why we do SROP the way it is. We put them in groups together, so it’s not like you’re in a lab by itself. You can talk about your experiences; you can share ups and downs and encourage each other.”

Wong claims the cohort model is important when recruiting, especially underrepresented students. “You don’t lie about the demographics of the university. It’s a primarily white institution...a majority school. So a lot of times, it’s unusual for our students of color because it might not be their experience.”

He acknowledges that students coming from smaller schools can feel overwhelmed. “This is a huge school, so it’s easy for them to get lost. The idea is to provide them that group so they can encourage each other.”

Left to right: Jannette Rodriguez-Otero with her SROP friend, Anthropology grad student, Beatriz Moldano.

To this day, members of Rodriguez's SROP cohort have still been providing encouragement. When she returned this past summer to attend Summer Pre-Doctoral Institute (SPI), she knew one student already. “I already knew him from SROP, so it was easier when I came here for that SPI: ‘I don’t know everybody, but I know him!’ And another SROP friend is here in Anthropology. “She is with me all the time," admits Rodriguez.

Rodriguez-Otero’s next visit to Illinois was in fall 2014 for ASPIRE, another of the Graduate College’s efforts to reach the underserved. Of that experience, she qualifies, “I got to know the mentor in the SROP, but for ASPIRE I got to know the department and the school. I got to know the coordinators, and I got to know the head of the department I wanted to be in, and I got to know all their mentors.”

Even during ASPIRE, she was still reaping benefits from SROP. She claims the folks in her department “were very interested in what I was doing before, and it was very nice to have the opportunity to tell them what I was doing here.” Being able to tell them, “I’m doing research; I’m not just studying,” was a real plus.

She also appreciated ASPIRE’s early application process. “That’s helpful. A lot. So even though MCB doesn’t allow that, I still did my process earlier. There’s a difference when you do a last minute application…and when you send in all your information on time.” Rodriguez contends that procrastinating says something about one’s character—hints at what kind of student one might be. She believes “They’re actually evaluating” even during the application process. “It says something about you,” she insists.

Enrolled as a graduate student for fall of 2015, Rodriguez-Otero came to spend one more summer at Illinois, this time as part of the Graduate College’s Summer Pre-Doctoral Institute (SPI). While the purpose of the SPI is to help incoming students become familiar with campus, give them a research opportunity, and show them the ropes about grad school, Rodriguez-Otero, an old hand at Illinois’ summer programs, didn’t need that as much as she did the support of her cohort personally. She admits to being extremely homesick, and her friends in SPI helped with that.

“It still helped,” she says of the SPI, “because every time I came here before SPI, I knew that I was coming back home, so…when I came here, I knew that it wasn’t going to be like that—it was going to be until December. So it’s like, ‘Okay, I’m getting depressed; I’m getting homesick,’ and they really helped me through that.”

MCB graduate student Jannette Rodriguez-Otero at her lab in Morrill Hall.

As with SROP, she’s still friends with her SPI cohort. “We get together sometimes and do stuff. We got together for Labor Day. We actually did a barbeque, and it was very nice to see everybody.”

Although she reports that at first, she didn’t connect that well with the folks in her SPI, “since I was a little bit depressed,” she indicates that that all changed at an SPI reunion: “We all had the opportunity to say what was going on with us, to say, ‘This is going on with me,’ and no one knew about it…and they helped me through that,” she acknowledges.

SPI staff and students alike rallied round her. “They were like, ‘Okay, you can do this!’ So I think that all this helped me get that personal help. Because the family’s important, and friends are important, but sometimes when they’re not here, you need someone that’s physically here to help you through things, and I think that I’ll build that kind of relationship with SPI.”

What are Rodriguez’s career plans, now that she's no longer going to barber? Although she first had planned to be a teacher, she later decided she wants to be a professor, so she can both teach and do research. Whatever she does, she wants her work to count.

“I just want to bring something to the table, something that will help a bigger research. Maybe not a breakthrough... I’m not hoping for that. If it comes, ‘Yea, thank you, that’s ok.’ But if I cannot do something like that in my career, I want to make sure that my work means something.”

So let’s get down to one final, very important question. Coming from a warm-weather clime, how does she really feel about the Illinois weather? Has she gotten used to it? “I really liked the University since the first time I came; I really like the campus, and even though it was cold, I really liked the weather.” She admits, “Sometimes I complain about it, but I think I would do the same if I were back home.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

More: Biology, Grad, Student Spotlight, Summer Research, 2015

For additional istem articles about programs in the Educational Equity Programs Office that target under-represented students, see:

SROP alumnae Beatriz Moldano and Jannette Rodriguez-Otero by Alma Mater.

.jpg)