Health Make-a-Thon Encourages Local Citizens to Dream Up Ideas for Improving Health

Amaury Saulsberry, a member of the winning team who dreamed up Nouvou, the Smart Pacifier, shows off their prize, a "coin" worth $10,000 in Health Maker Lab Nodes services.

April 22, 2019

Dream it; make it! This pithy slogan epitomized the Carle Illinois College of Medicine’s (CI MED) recent Health Make-a-Thon, whose lofty goal was to democratize health innovation. The aim of the competition was to foster innovative ideas for improving human health by offering a huge incentive: a chance for contestants to win $10,000 in Health Maker Lab resources to create a real prototype of their idea.

Regarding the term “democratize,” Libby Kacich, the CI MED Communications and Marketing Director, explains it like this: “So, to bring literally anyone in Champaign County into a role of being empowered to bring ideas for improving health care to life.” Chemistry Professor Marty Burke, the College’s Associate Dean for Research, alludes to the “everything-I-need-to-know-I-learned-in-kindergarten” mentality, defining democratization as: “to invite everyone into the sandbox.”

“It’s all about creating excitement,” adds Irfan Ahmad, CI MED's Assistant Dean for Research and Executive Director of the Health Maker Lab. “That ‘I have a role to play, that it is my health, and it is my family’s health, and things can be done differently!’”

The brain trust behind the Make-A-Thon concept, besides Ahmad, Burke, and Kacich, also included Sociology Professor Ruby Mendenhall, the College’s Assistant Dean for Health Innovation and Diversity; Rachel Switzkey, Director of the new Siebel Center for Design; and Lisa Goodpaster, CI MED's Associate Director for Project Management. This planning committee developed then facilitated the idea of a contest with a $10,000 incentive. According to Ahmad, the prize would not be cash or a check, but a coin that’s symbolic of funds to access or leverage existing University of Illinois resources to develop a prototype in the College's Health Maker Lab.

Ruby Mendenhall and Marty Burke welcome participants and audience members to the final competition.

Contestant Dena Strong (right) answers questions about her idea: a programmable pill bottle.

Paula Abdullah (left), a retired nurse and a community member on the Dolphin Tank, interacts with a contestant during a Q&A session. To her right is Dolphin Tank member Margarita De L Teran-Garcia, Extension Specialist Hispanic Health, Research Assistant Professor, Human Development and Family Studies; ACES Division of Nutritional Sciences, C.I. MED.

Paula Abdullah (left), a retired nurse and a community member on the Dolphin Tank, interacts with a contestant during a Q&A session. To her right is Dolphin Tank member Margarita De L Teran-Garcia, Extension Specialist Hispanic Health, Research Assistant Professor, Human Development and Family Studies; ACES Division of Nutritional Sciences, C.I. MED.Exactly what is the Health Maker Lab? It’s a network comprised of 18 nodes—cutting-edge maker labs and design spaces across campus that are involved with CI MED and agree on the importance of improving the world’s health. What’s exciting about the Health Maker Lab is that it’s integrated colleges not previously involved with the College of Medicine: Architecture, Art and Design, Veterinary Medicine, and Agriculture. “All of them now are so excited that somebody has reached out to them,” says Ahmad, “and are leveraging their resources for the good of the campus and also opening them to other avenues.”

How are architecture or art and design related to health? Ahmad responds by citing some research:

“Artistic displays in children’s hospitals in Indianapolis and downtown Chicago—the murals on the walls—have shown to help healing of children. So there you are. So you can be an artist, but you can relate it to health and care and wellness of the patient.”

Once the competition details were finalized, advertising began via billboards, MTD busses, flyers and posters plastered around campus, even social media. Plus, Ahmad, Mendenhall, and others gave informational sessions about the Make-A-Thon in the community. Sessions were intentional about increasing diversity of thought among participants. For example, to get African-Americans involved, a meeting was held at the Douglass Center library. Regarding the emphasis on diversity, Mendenhall, in her role as Assistant Dean for Health Innovation and Diversity, explains:

"When we expand the conditions for everyone to be a part of innovation, we infinitely expand the possibilities of solving our most troubling grand challenges."

Here’s how the Health Make-A-Thon worked. From February 11th through March 11th, 2019, local folks were to submit their ideas, individually or in groups via either two-minute video clips that could be uploaded by cell phone or one-page write-ups answering three questions: What is the goal or idea? How will you go about doing it? How does it impact the community and the society that we live in?

When this reporter informally proffered her suggestion, the need to somehow make health care less expensive and accessible to everyone, Kacich agreed:

“Lower costs, better care, and better accessibility are the three tenets that this College was established on,” she affirms. “That’s our whole reason for being; that’s what we’re here to try to figure out.”

“That’s exactly the kind of idea that we are looking for,” Ahmad agrees, then describes a couple of hoped-for scenarios, such as a family sitting at the dinner table talking and then coming up with an idea for the Make-A-Thon, or a group of friends sitting in a coffee shop brainstorming about an idea.

“Because what we want is to make Urbana-Champaign at the University of Illinois the epicenter of health innovation in the country and the world,” Ahmad acknowledges. “And this is the first step towards it.” Because while this year’s Make-A-Thon was limited to Champaign County, the idea is to go national then global in subsequent years.

During the final competition, one of the winners, Sarah Nixon, presents her idea: using miniature horses to provide psychotherapy for traumatized children. Sarah was among those who were made aware of the community-wide Health Make-a-Thon during an informational session at the Common Ground Food Coop in Urbana.

Quite a few folks registered ideas: 141 all total, submitted by entrepreneurs from the community, even elementary school students. In fact, contestants ranged in age from 8 to 85.

The next step was to review the submissions. So around 60 people were recruited to serve on panels of judges that reflect community demographics, including folks from academia; national labs; community partners; Carle health care providers; K-12 educators; non-government organizations; plus citizens from the general community and even from Chicagoland. Panels were comprised of people from five different broad categories:

“So that everyone’s perspective is brought into the decision, so that no idea goes by the wayside,” explains Ahmad, adding that the goal was “Health and wellness, defined very broadly.”

In fact, arguing that everything is related to health and wellness, he was hopeful that folks would think big, and maybe come up with an idea that has never been done before.

“Before the iphone or the cell phone came into being,” he explains, “we did not think that there would be a thing like this cell phone. We did not think that there would be a smart phone. But today we have that. Somebody was thinking, 10 years, 20 years down the road. This technology has changed the way we live and interact.” In fact, smart phones, which at first glance, appear to be totally unrelated to health, can now be used to monitor one’s health.

Next, the panels reviewed the submissions and narrowed the group down to 20 finalists, which were invited to the Health Make-A-Thon Orientation held on March 28th. There, committee members presented to the finalists and answered questions. For instance, Marty Burke welcomed the group, facilitated introductions, and explained the Make-A-Thon’s philosophy and strategy. He also explained that the Dolphin Tank would be a panel of friendly judges (as opposed to the more menacing “Shark Tank” on the tv show of the same name, where contestants face a sometimes vicious panel of entrepreneur judges).

Marty Burke shares the Make-A-Thon philosophy during the Orientation session.

Rachel Switzky, Director of Siebel Center for Design (SCD) encourages the contestants to tell their story during the Make-A-Thon Orientation.

Burke also explained about the Health Maker Lab, followed by Irfan Ahmad who also welcomed the group and further discussed the many university resources available to contestants. Also sharing was Libby Kacikch, who succinctly explained (in two minutes?) how to prepare a two-minute elevator pitch.

Rachel Switzky exhorted contestants to tell their story and to make sure their design reflects their audience. One story she told was that of an MRI designer, who, after seeing a small child being dragged kicking and screaming to the MRI he’d designed for adults, changed his tactic to make a more kid-friendly one shaped like a boat. The presentations were followed by an optional Autodesk workshop, taught by Dan Banach and designed to give contestants another tool at their disposal.

Next, in preparation for presenting their idea to the Dolphin Tank, finalists were connected with mentors—campus experts whose areas of expertise were closely related to the contestants’ ideas and who would help them in regard to broad design thinking, presentation preparation, and software.

Finally, during the competition’s April 13th final event, a gala evening which Ahmad likened to a festival and Burke a “rock concert,” the 20 finalists presented in person before the audience, which included participants' family and friends, plus several international visitors from Agha Khan University, Karachi, who have held multiple health hack-a-thons. Of course, also at the event were the members of the Dolphin Tank, who were integral to the competition. This group was made up of specialists, including entrepreneurs, innovators, academics, community members, and also some industry members from Chicago—venture capitalists who, according to Ahmad, have “been there, done it.”

For example, one member of the Dolphin Tank was Mukund Chorghade, an academic and President and Chief Scientific Officer of THINQ Pharma/THINQ Discovery. He shares why he agreed to be a Health Make-A-Thon judge:

Mukund Chorghade asks a participant a question during one of the Q & A sessions.

King Li (center), Dean of the Carle Illinois College of Medicine (CI MED), interacts with one of the contestants. Pictured on his right is Khan Siddiqui, CEO of Higgi, Inc. Chicago, and on his left Steve Boppart, Executive Associate Dean and Chief Diversity Officer for CI MED. All three were part of the Dolphin Tank.

“I've always been fascinated with entrepreneurship,” he admits. An inventor who’s started some bio-tech companies himself, he reports: “I preach this gospel in American Chemical Society and other forums. So when Martin invited me to do this and encourage young entrepreneurs, I was extraordinarily thrilled and extraordinarily impressed.”

Chorghade shares about the impact he believes the competition could have on the face of healthcare. “First of all, this is a contest that is truly democratizing the science; there are no ‘haves’ or have-nots.’ There are some very clever people who are coming up with very innovative concepts which are truly designed to change the face of healthcare.”

While he claims that America has the best healthcare system, he adds that there are still some things that need to be improved. “In my opinion, the biggest thing that needs to be changed is that non-doctors and non-physicians need to be brought in a very healthy discussion of their own interests.” He goes on to call some of the Make-A-Thon projects “absolutely stunning in scope, diversity, and in breadth, and I think it will make the best use of the most creative minds in America, and that's what America is all about.”

The Dolphin Tank also included Dr. King Li, Dean of the Carle Illinois College of Medicine, who shares the impact the College hopes to have on healthcare:

Our vision is to leverage engineering, technology and data science to increase quality, accessibility and equity while decreasing cost of healthcare. To democratize this healthcare innovation process, we want to give the power of turning ideas into prototypes to all citizens of the world eventually."

Another Dolphin Tank member was Rashid Bashir, Dean of the College of Education. Regarding Illinois' committment to health, Bashir says:

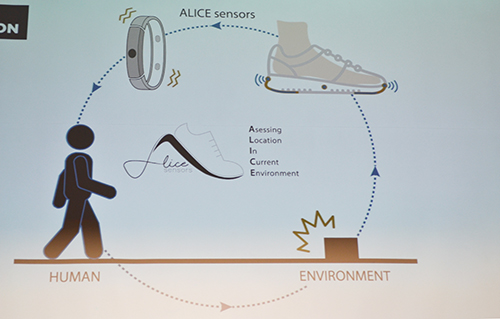

A member of the ALICE team, Mikaela Frechette, presents during the final competition. The idea was inspired by Ramadhani's experience with her grandmother, shown in the image on the screen.

A diagram detailing how the ALICE device will work.

"The College of Engineering and campus at large have made major investments in healthcare and medicine—not the least of which are the Carle Illinois College of Medicine, the Jump Simulation Center, and dozens of faculty across all disciplines who work at the intersection of medicine and engineering. That has tremendous research and educational impact in and of itself. But it is also exciting to see that investment have an impact in the community. The Health Make-A-Thon reminds us that there are innovators everywhere, and we’re proud to encourage them and give them the support they need.”

At the final event, each participant or team gave their exactly-two-minute tech talk (a buzzer would sound to interrupt them!) followed by a friendly Q&A session during which they responded to questions from the Dolphin Tank, who then, along with audience members, were given exactly one minute to vote on each idea presented. During the event, presenters also had a chance to network with other experts, like the Dolphin Tank members. By the evening’s end, the 20 finalists had been narrowed down to 10 winners, who each received their $10,000 coin.

One of the winners was a group of three students who proposed a device that measures four vitals: pulse, respiration rate, blood pressure, and temperature. Another team submitted an idea for a compression stocking which would use a material such as a memory metal (Nitinol, perhaps?) making it much easier to put on.

Many of the ideas submitted were based on personal experience, either of the contestant or a loved one. For instance, one winning team submitted an idea for ALICE (Assessing Location in Current Environment) sensors, designed to help someone, such as an elderly person, safely navigate while walking. Team member Widya Ramadhani came up with the idea because of her experience with her grandmother.

Yusef Shari'ati, who, along with his wife Siddiqua Shari’ati, came up with the idea for the Mobile Phototherapy Suit. The idea was inspired by their son, Adam, who had jaundice as a newborn.

Another winner was inspired to design a programmable pill bottle because her father has Parkinson’s, diabetes, and high blood pressure, and has trouble keeping track of his medicine, to be taken both with and without food, once, twice, even four times a day.

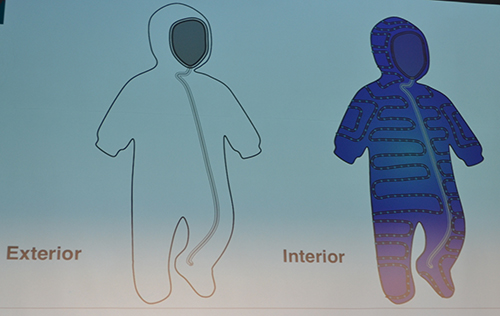

Similarly, Siddiqua Haswarey-Shari’ati, who teaches at the DEEN Homeschool Coop in Urbana, and her husband, Yusef Shari'ati, came up with their idea for a mobile phototherapy suit because of their experience when their son was born. He was jaundiced and had to undergo treatment to bring down the high levels of bilirubin in his blood. But because he had to remain under the lights, the couple couldn’t hold him; plus their newborn had to wear a mask so his eyesight wouldn’t be injured. So the couple spent a few sleepless nights by his incubator touching him and making sure he hadn’t knocked the mask off. It was that personal experience that gave them the idea of a phototherapy suit so other parents wouldn’t have to undergo such a traumatic experience during what should be a joyful time. (I [this writer] also had a jaundiced newborn, and when I heard their idea during the orientation session, I was immediately cheering for them and knew they would be one of the winners!)

Following the final ceremony, winners were free to get started at any point (even the next day, according to an Orientation Q&A response!). Over the next year, winners will work with campus experts/ mentors to make a plan for creating a prototype, figure out which facilities or labs to use, then develop their prototype. “So as soon as you get that coin,” Ahmad explains, “you will have the ability to use any of those labs that you saw that are part of the 18 nodes or labs that comprise the Health Maker Lab.”

What do contest designers expect from the winners? They’ll have one year to work on their project, then come back to the next annual event to present about their experience and the status of their idea. Regarding long-term expectations, it is hoped that at least one or two of the 10 finalists will be successful. And while they’re not expected to go beyond making a prototype, if some do decide to move on to the start-up phase, they’ll be connected with Illinois’ research park and other resources.

The Shari'ati's design for the Mobile Phototherapy Suit, which is lined with strings of LED lights.

One of the finalists, Adam Taggart, presents his idea for a Modular Prosthetic Skeleton.

What about those not chosen as winners? Ahmad says they hope to help nurture their ideas further. “So they’re not going to be left by the wayside,” he says.

Regarding the whole democratization notion, can amateurs, non- engineers and/or with no experience in medicine, like middle or high school students, really come up with a ground-breaking idea that will majorly impact health care?

Ahmad reiterates “All ideas are welcome as long as they relate to health and wellness,” indicating that, “We have seen around the country, and actually the world, that more creativity has come from these school kids and they have taken an idea and taken it to the next level. So we are very hopeful that some of our kids in the school system and beyond would do it, and be excited about it.”

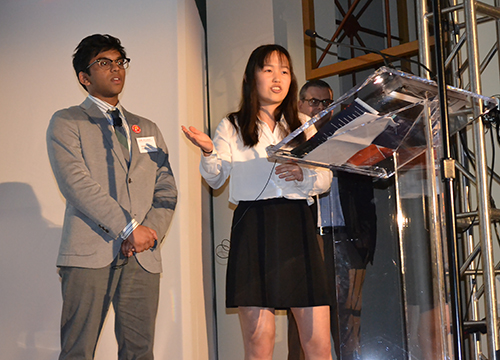

So the Make-A-Thon planners were quite excited when two teams of K-12 students made the field of 20, including a team from University Laboratory High School, Maher Adoni and May Yang, whose idea was Hydrosupport Bone Implant, and a team of elementary students from Garden Hills Academy in Champaign who presented their idea for an In-School Health and Wellness Space.

Kacich further explains the founders’ demoncratization philosophy: “I think the major benefit from this whole initiative is the movement towards turning health care on its head...empowering patients and people, and the public to inform the care that they receive, and giving them a more powerful voice and role in that process...so stepping away from the top-down process that we currently have in health care.”

Rashid Bashir, Dean of Illinois' College of Engineering and a member of the Dolphin Tank, appreciates a contestant's response to his question.

Indicating that their competition is a move in that direction, she further clarifies their vision regarding democratizing health care:

“The whole idea is that there’s not an upper echelon that is bringing care down, but more we’re empowering people to recognize what they need and to have a voice and to make the right connections with the experts in those fields so that they can work together, so that it’s more of a team approach.”

Story and photos by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative.

For more related stories, see: Carle Illinois, 2019

For an additional I-STEM articles about Carle Illinois College of Medicine, see:

- The (Future) Doctor is in the House: Meet an Illinoisan in the Inaugural Carle Illinois Medical Program

- Underrepresented Minority Undergraduate Students Gain Research, Clinical Experience Via the Carle Illinois College of Medicine’s New REACH RCEU

- Undergrad Brione Griffin Gets One Step Closer to Her Dream of Becoming a Doctor Via REACH RCEU

Libby Kacich and Irfan Ahmad chat during the Health Make-A-Thon Orientation held at the Beckman Institute.

Yusi Gong, from the inaugural cohort of CI MED students, presents her team's idea, a Smart Toilet, while team member Gwendolyn Derk interacts with the Dolphin Tank via a remote link from overseas.

Aadeel Akhtar, an up-and-coming entrepreneur and member of the Dolphin Tank, votes during the competition. Akhtar also presented about his prosthetic start-up, Psyonic, while the votes were being tallied at the end of the competition. Familiar with competitions, Akhtar, along with Psyonic co-founder, Patrick Slade, won the Cozad New Venture Competition in 2015, which helped them begin their start-up. Sitting on his left is Dolphin Tank member Stephanie Pitts-Noggle, Business Specialist and Leader of the Youth Entrepreneur Program at the Champaign Public Library.

Laura Frerichs (center), Director of the Illinois Research Park and Director of Economic Development in the Office of Public Engagement, asks a question during a Q & A session. To her right, Marissa Siero casts her vote. Siero is co-founder of the Intelliwheels startup that offers products for wheelchair users. Sitting behind them is entrepreneur Ben Barbieri, CEO of ISS, Inc. They were all part of the Dolphin Tank.

Laura Frerichs (center), Director of the Illinois Research Park and Director of Economic Development in the Office of Public Engagement, asks a question during a Q & A session. To her right, Marissa Siero casts her vote. Siero is co-founder of the Intelliwheels startup that offers products for wheelchair users. Sitting behind them is entrepreneur Ben Barbieri, CEO of ISS, Inc. They were all part of the Dolphin Tank.

Ruby Mendenhall (left) and Marty Burke (second from the right) shake hands with one of the winning teams, who proposed a device that measures human vital signs.

University Laboratory High school students, Maher Adoni and May Yang, pitch their idea, a Hydrosupport Bone Implant.

A team of Garden Hills Academy elementary students present their idea for an In-School Health and Wellness Space, accompanied by Melissa Kearns, Magnet Site Coordinator.

.jpg)