Leal’s Career Grant: Research in Soft Materials, GLAM-Mid Camp for Girls, Workshop for Incarcerated Adults

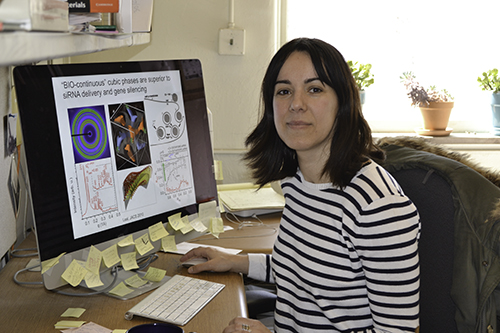

MatSE Assistant Professor Cecelia Leal

MatSE Assistant Professor Cecelia LealApril 24, 2017

Cecelia Leal, an Assistant Professor in Materials Science and Engineering (MatSE), was recently awarded a 5-year National Science Foundation Grant called, “CAREER: Nanostructured Soft Substrates for Responsive Bioactive Coatings,” to study key fundamental properties of biocompatible lipid materials. Because Career grants also require researchers to do an educational outreach component, in addition to the graduate students she’ll be training and mentoring, Leal will be doing a new summer camp for middle school girls and a workshop for incarcerated individuals as part of the Education Justice Project.

Leal's Research

Leal’s research is in soft materials. “I’m interested in studying the way that materials self-organize, or come together, to form a structure, how the geometry and how the properties of that structure affect the way they function.” Many of the materials she works with are biological, such as lipid membranes, which mimic a cell membrane, and nucleic acids. “So basically we are trying to understand how the structure of these materials, when we put them together in a test tube, how it affects the way they function when we use them in a biological application.”

Two students make snowflakes at the Snowflake Station.

Leal says one starts seeing especially interesting behavior of these materials at the nanoscale. “So these materials, if you look at them at the macro scale, or what you can see with your eye, they don’t look anything interesting, but when you start going down into the smaller and smaller sizes, you start seeing that they organize in spectacular structures, pretty much like what happens in biology. So there’s this magic range from micro scale to nanoscale where you see beautiful structures that actually have a meaning to them, and we’re trying to uncover what that meaning is.”

One practical application of her research would be to transport medicines, drugs, vaccines, antibiotics, etc., by designing smart materials able to interface with the human body to heal wounds, repair bones, plus “deliver medicine by a remotely programmable delivery system with the desired drug load at the correct location and predetermined time point.”

While some research on campus uses real viruses as a delivery system, Leal doesn't, but uses materials that emulate viral properties. She takes materials similar to those in cell membranes, then makes “materials or particles that are pretty much like a virus; they can contain DNA inside,” she explains, “and the idea is to use these materials or these nanoparticles to go from the outside of the cell to the inside of the cell and deliver cargo.” These nanoparticles could be designed to respond to a certain stimulus—an increase in temperature or a magnetic or electric field—by opening up to release cargo. “In essence, you could say this is nano-machine that we are operating from the outside.”

Although the nanoparticles don’t have a biological cell membrane, some lipids they use are compatible with biological and, in fact, actually do exist in the cell membrane too. While hers is a “very simplified membrane mimetic system” (a cell membrane has hundreds of different lipid categories; she uses three), they are compatible. The cell membrane recognizes them and says, “You’re okay, please come in!”

Leal calls her work “fundamental,” in the sense that it’s very far removed from the actual clinical application or translation. “There’s a lot to do before that. So my work is really understanding those first steps.”

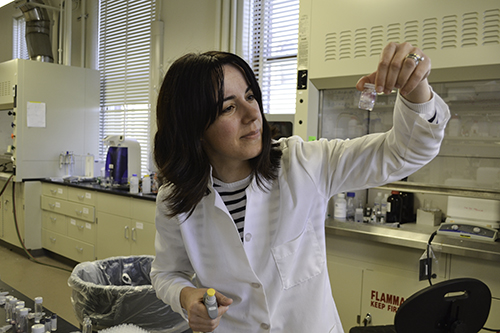

Leal at work in her MatSE lab.

Leal at work in her MatSE lab. In fact, she claims there’s even a need to understand particles or materials that are in use right now, for example, Doxil an FDA-approved product that’s been on the market for 20 years and is used in certain types of cancer treatment. Like the materials she uses, it’s a nanoparticle similar to a cell membrane that attaches to cancer cells and releases the cancer drug that’s inside. So " it works,” she says, “but there’s so much we don’t understand still about that system. What is exactly happening at the molecular level? What are the exact mechanisms at which these particles approach a cell and make their way in? And sure, you found something that works, but it doesn’t work for everything, but if you know exactly how it works, then you could possibly design something that works for many things.”

So Leal's work is, “Not so much pushing to offer yet another product in the market, but trying to understand the fundamental properties of these particles and how they work in the human body... I’m very far from offering a real medicine, but that doesn’t mean it’s less important.”

GLAM-Mid

In addition to the research, another key aspect of a Career grant is educational outreach. So Leal chose to do something about which she is passionate: outreach to girls. With the help of colleague Robert Maass, this summer, she's launching a day camp for middle school girls. Called GLAM-Mid, it's patterned after its GAMES counterpart for high school girls, GLAM (Girls Learning About Materials). And like its name (part of which it borrowed from its older sibling), the camp will similarly address Materials Science. However, unlike its big sister, GLAM-Mid will not be a residential camp, but a day camp, and will, thus, draw only from local clientele. For GLAM-Mid’s inaugural run, Leal is partnering with Campus Middle School for Girls, and already has 15 girls signed up, with attendance to be capped at 20.

One reason Leal chose to do a GAMES camp was so she wouldn't have to reinvent the wheel. "I wanted to basically build on efforts that were already in place at the university. I didn't want to start anything completely new. So I went to an information session organized by the college on the sort of outreach activities our campus is running and how I could tag along in some of those." So Leal and Mass will have some help in running the camp. Under the GAMES (Girls umbrella, they'll have help from Sahid Rosado and her team that oversees GAMES; plus Illinois grad students will help in developing the curriculum for the camp; and undergraduate students to help run it.

While Leal’s research is keeping her busy, she’s still finding time for outreach because she’s committed to inspiring girls, especially, to pursue STEM; she hopes to inspire confidence, to deliver the message, “We can do this. We can do math; we can do science, right?”

The need for this message to girls flies in the face of the social paradigms that appear to be instilled in youngsters at a very young age. Leal shares an extremely apropos anecdote about a recent demonstration she did at her daughter’s preschool class:

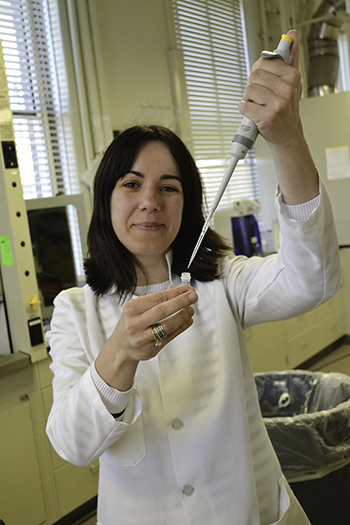

Leal uses a diffuser in her lab.

Leal uses a diffuser in her lab. “This happened. This is a true story. When I gave my little crystallization experiment for the class of my four year old—this is a true story—a four-year-old boy, beautiful, sweet little boy had a question after I did my demonstration. He said, “So you are a scientist?” and I said, “Yes.” And he said, “Don’t you have to be a boy, first?” (This is true story. This happened two weeks ago.) And I said, “No, you can be a boy and be a scientist. You can be a girl and be a scientist. You can be whatever you want and be a scientist; it’s fine!” And then he asked, “Can I be a superhero and a scientist?” and I said, “You sure can!” And then they asked me, “Can I be a princess and a scientist?” “Of course” And then my daughter said, “Yes, you are a Mommy and a scientist,” and I was like, “That’s right, I’m a Mommy and a scientist.”

Based on that interaction, Leal believes it’s never too early to start encouraging little girls that they too can be scientists. “So yeah, I’m very passionate about that. I think females you need to encourage from early on, ‘It’s possible; we can do this; we can be scientists; we can be parents; we can do anything. If you’re curious, and if you’re hardworking, your gender shouldn’t be in the way.’”

Education Justice Project

Another outreach effort that’s up and running that Leal has gotten involved with is the Education Justice Project, a program designed to offer college-level courses to incarcerated students in order to promote the positive impacts of higher education. However, it’s quite different from her outreach to middle school girls.

“For the Education Justice Project, it’s a different goal,” Leal explains. “These are adults who have been incarcerated and have an interest in learning.” Right now, the program offers courses in many different fields such as robotics, programming, physics, and mathematics. Leal’s goal is to soon establish a four-credit hour Material Science and Engineering course. “We started by offering workshops where basically I go to Danville, and I spend three hours with the students, and we discuss.”

Leal is hoping that in her last two years of her career project, she will be in a position to offer a full course. Although hands-on activities are difficult to do because of regulations, she still finds a way to keep the students interested and engaged. Leal says that she “just brought paper and we have old-school class where there’s only a blackboard. It worked out great actually. They were very engaged.” She gives the students exercises and problems for them to solve about different topics, such as how DNA can store information. “We go over the math on the board, so it’s more interactive in that way.”

Story and photographs by Elizabeth Innes, Communications Specialist, I-STEM Education Initiative and Megan Sullivan, Undergraduate Student Worker, I-STEM.

For related articles, see:

- Girls Learn About Materials Science at the 2016 GLAM G.A.M.E.S. Camp

- GLAM Seeks to Capture Girls' Imagination About Materials

- Education Justice Project: Motivating Prison Scholars for Change

More: Engineering, Faculty Feature, 2017, Women in STEM

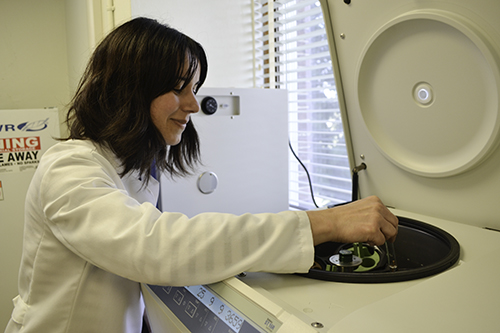

Leal discusses the properties of one of the materials she's researching.

Leal discusses the properties of one of the materials she's researching.

.jpg)